[ad_1]

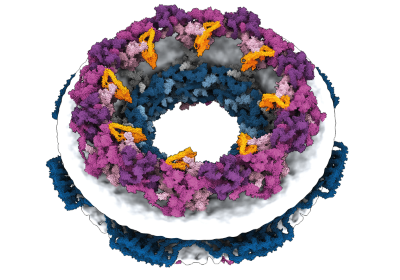

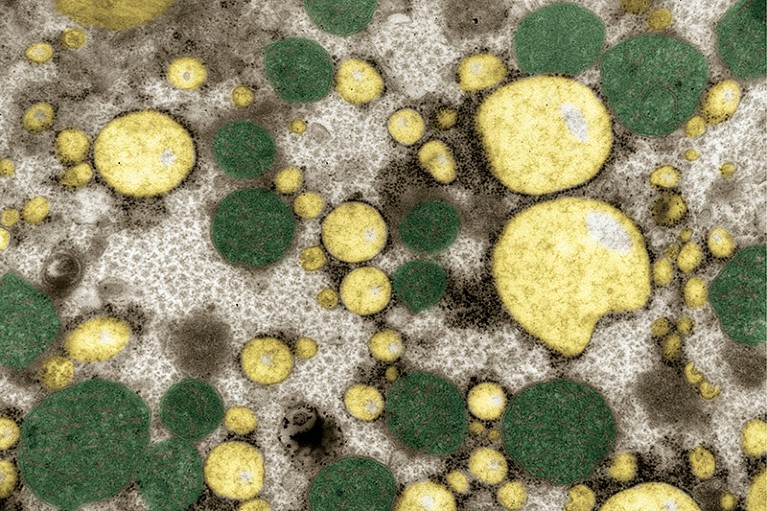

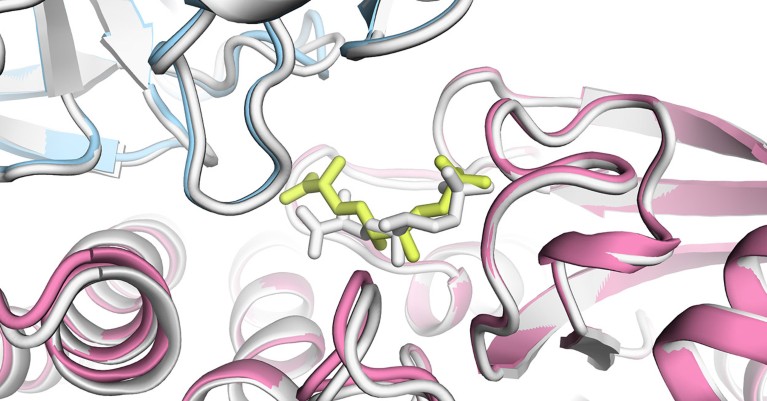

An AlphaFold3 model of a bacterial enzyme bound to a chemical.Credit: Isomorphic Labs

Since the powerhouse artificial intelligence (AI) tool AlphaFold2 was released in 2021, scientists have used the protein-structure-prediction model to map one of our cells’ biggest machines, discover drugs and chart the universe of every known protein.

Despite such successes, John Jumper — who leads AlphaFold’s development at Google DeepMind in London — is regularly asked whether the tool can do more. Requests include the ability to predict the shape of proteins that contain function-altering modifications, or their structure alongside those of DNA, RNA and other cellular players that are crucial to a protein’s duties. “I would say ‘no, you can’t put that into AlphaFold’,” Jumper says. “I would rather solve their problems.”

What’s next for AlphaFold and the AI protein-folding revolution

The latest version of AlphaFold, described on 8 May in Nature1, aims to do just that — by giving scientists the ability to predict the structures of proteins during interactions with other molecules. But whereas DeepMind made the 2021 version of the tool freely available to researchers without restriction, AlphaFold3 is limited to non-commercial use through a DeepMind website.

Frank Uhlmann, a biochemist at the Francis Crick Institute in London who gained early access to AlphaFold3, has been impressed with its capabilities. “This is just revolutionary,” he says. “It’s going to democratize structural-biology research.”

Another revolution

“Revolutionary” is how many scientists have described the impact of AlphaFold2 on biology since it was unleashed2 (the first version3, released in 2020, was good, but not game-changing, Jumper has said). The AI predicts a protein’s structures from its amino-acid sequence, often with startling accuracy that is on par with that of experimental methods.

A freely available AlphaFold database holds the predicted structure of nearly every known protein. The availability of the AlphaFold2 code has also allowed other researchers to easily build on it: an early hack enabled the prediction of interactions between multiple proteins, a capability included in an update to AlphaFold2.

Jumper’s ennui over explaining AlphaFold’s inability to predict other aspects of a protein’s ecosystem stems from their importance: protein modifications, such as the addition of a phosphate molecule, can allow cells to respond to external cues, an infection, for instance, and set off a chain of events in response. Interactions with DNA, RNA and other chemicals are essential to many proteins’ duties.

Real-world examples of these interactions are readily available in the Protein Data Bank (PDB), a repository of experimentally determined structures that is the foundation of AlphaFold’s capabilities. An ideal tool would be able to predict structures of a protein alongside its accessories, says Jumper. “We want to solve the whole PDB.”

Major upgrade

To create AlphaFold3, Jumper, DeepMind chief executive Demis Hassabis and their colleagues made large changes to its predecessor: the latest version depends less on information about proteins related to a target sequence, for instance. AlphaFold3 also uses a type of machine-learning network — called a diffusion model — that is used by image-generating AIs such as Midjourney. “It’s a pretty substantial change,” says Jumper.

AlphaFold’s new rival? Meta AI predicts shape of 600 million proteins

AlphaFold3, the researchers found, substantially outperforms existing software tools at predicting the structure of proteins and their partners. For instance, scientists — especially those interested in finding new drugs — have conventionally used ‘docking’ software to physically model how well chemicals bind to proteins (usually with help from the proteins’ experimentally determined structures). AlphaFold3 proved superior to two docking programs, as well as to another AI-based tool called RoseTTAFold All-Atom4.

Uhlmann’s team has used AlphaFold3 to predict the structure of DNA-interacting proteins involved in copying the genome, a step that is essential to cell division. Experiments in which proteins are mutated to alter such interactions suggest that the predictions were usually spot on, Uhlmann says. “It’s an amazing discovery tool,” he adds.

“The structure-prediction performance of AlphaFold3 is very impressive,” says David Baker, a computational biophysicist at the University of Washington in Seattle. It’s better than RoseTTAFold All-Atom, which his team developed4, he adds.

Restricted access

Unlike RoseTTAFold and AlphaFold2, scientists will not be able to run their own version of AlphaFold3, nor will the code underlying AlphaFold3 or other information obtained after training the model be made public. Instead, researchers will have access to an ‘AlphaFold3 server’, on which they can input their protein sequence of choice, alongside a selection of accessory molecules.

How AlphaFold can realize AI’s full potential in structural biology

Uhlmann likes what he has so far seen of the server, which he says is simpler and quicker than the version of AlphaFold2 that he has access to at his institute. “You upload it and 10 minutes later, you’ve got the structures,” he says. For most scientists, “the server is really going to smash it. Everybody can do it.”

Access to the AlphaFold3 server, however, is limited. Scientists are currently restricted to 10 predictions a day, and it is not possible to obtain structures of proteins bound to possible drugs.

Isomorphic Labs, a DeepMind spin-off company in London, is using AlphaFold3 to develop drugs, both through its own pipeline and with other pharmaceutical companies. “We have to strike a balance between making sure that this is accessible and has the impact in the scientific community as well as not compromising Isomorphic’s ability to pursue commercial drug discovery,” says Pushmeet Kohli, DeepMind’s head of AI science and a study co-author.

Because of the restriction on modelling protein interactions with possible drugs, “I can’t see it having the impact AlphaFold2 had”, says Brian Shoichet, a pharmaceutical chemist at the University of California, San Francisco, who has been using AlphaFold structures to hunt for therapeutic candidates.

Sergey Ovchinnikov, an evolutionary biologist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, had hoped to develop a web version of AlphaFold3, as he and his colleagues have done for AlphaFold2 shortly after its code was released. But based on the ample information provided in the latest Nature paper, it shouldn’t take long for other teams to create their own versions, he says. “I would expect open-source solutions before the end of the year.”

[ad_2]

Source Article Link