[ad_1]

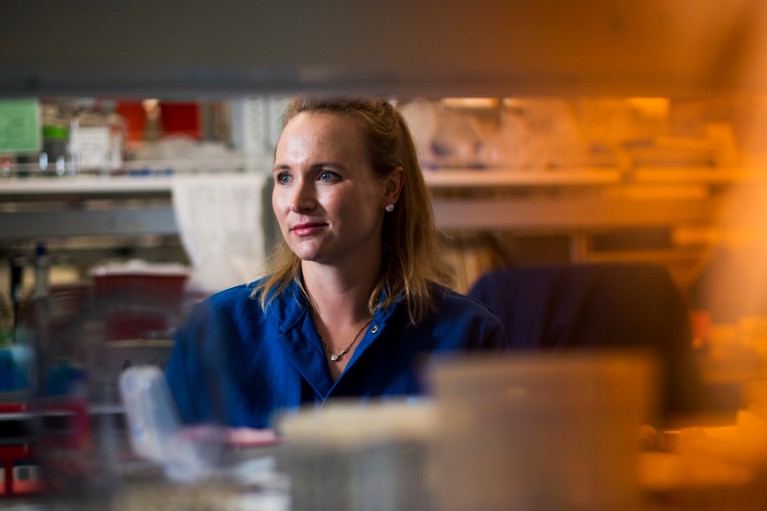

A member of the rebel Free Syrian Army walks past a burnt-out Syrian army tank in northern Aleppo province in 2012.Credit: Daniel Leal/AFP/Getty

Aref Kyyaly has a guiding principle: don’t give up. That might sound clichéd or trite, but in his journey to find a stable job and a safe place to live, he and his wife have been stretched and tested to the extremes. He’s been separated from his family, seen his workplace blown up, sustained physical injuries and been forced into an asylum-seeker system that he was desperate to avoid.

Kyyaly was born in 1978 in Aleppo — a city in Syria then famed for its bazaars and historic citadel, rather than for being war-torn. He studied applied chemistry at the University of Aleppo, and met his wife, Razan, in 2006 before they went to Egypt, where he pursued a PhD in biochemistry at Cairo University.

When they returned to Syria in 2009, he soon found work as a researcher in a factory that was one of the country’s biggest producers of yeast, while also lecturing part-time at his alma mater. Things were looking good. But the Syrian revolution broke out in 2011, and the ensuing civil war saw armed groups with differing world views — ranging from the Free Syrian Army to ISIS — take over large swathes of the country. The Syrian regime’s army had a base close to the factory, and militias opposed to it began to use the factory grounds to launch rockets at the base, which in turn made the factory a target.

Freedom and safety in science

“We were commuting during the clashes. If we stopped [operating the factory] there’d have been no bread, so we worked seven or eight months under these conditions and it was really hard, because you’d see people dying in the streets and you couldn’t do anything,” he remembers. “We kept doing that until the factory was completely bombed by airplanes.”

Then came money problems. “I had no real work; I was only part-time at the university and the value of the currency dropped at the same time.” His monthly salary, which had been worth around US$400, went down to the equivalent of around $50. “I couldn’t afford to buy anything,” he says. Despite the financial stresses, Kyyaly was still trying to remain in Syria. “I’m my parents’ only son,” he explains. But when he was seriously hurt in an explosion, he finally resolved to get himself, his wife and their two children out. He and his wife had a third child once they left Syria.

He started to send e-mails to everyone he knew who worked at universities abroad. He also contacted many people he didn’t know. At one point he got an offer to work in Libya, but it fell through before he could travel. “In retrospect, I’m lucky that happened,” he says, because Libya was descending into its second civil war in 2014.

Of the 50 or so e-mails that Kyyaly sent, one landed in the inbox of the Council for At-Risk Academics (Cara), an organization based in the United Kingdom that tries to help scholars around the world who are forced to flee owing to a high risk of imprisonment, injury or death. Cara tries to find positions for researchers such as Kyyaly in safe countries, offering both practical and financial support to make that happen. The majority of people he contacted didn’t reply, so he was surprised when Cara called him in 2014. He moved to the United Kingdom later that year. “It was like a door was opened for me.”

How three refugee scientists kept their research hopes alive

Zeid Al Bayaty, Cara’s deputy director, was behind the call. At the time, Al Bayaty was also in touch with a number of other Syrian scholars. “When Syrian applicants heard about Cara, they were convinced that it was too good to be true and some of them were quite suspicious,” he says. But once the first cohort of Syrians had arrived to join Cara’s fellowship programme, “they told colleagues back in Syria and then the number of applications significantly increased. Aref was in that first early wave,” he says.

At the peak of the war in Syria, Cara was receiving about 20 applications per week, says Al Bayaty. When Russia invaded Ukraine, Al Bayaty and his colleagues expected a similar influx of calls from researchers looking to leave. But it didn’t quite pan out in the same way. “There were a number of situations where we placed Ukrainians at [UK] universities, but they then chose not to come because they had other opportunities on the continent and they chose to go to Germany instead,” he says. “Don’t get me wrong, it’s great that the visas were more straightforward for Ukrainians and so they had options. We just wish it was like that for more countries in conflict.”

Most applications today are coming from scientists in the Palestinian territories and Sudan, says Al Bayaty.

Within six months of that first call with Al Bayaty, Kyyaly was on a one-way flight to the United Kingdom. Cara had helped him to secure a visa and find a job as a research associate in the International Centre for Brewing Science at the University of Nottingham. But it was another eight months before the paperwork for his wife and children could be sorted out. Leaving them behind was incredibly tough, he says. “You can imagine what it was like when you listen to the news,” he says. “It was very, very horrible at times.”

After spending a year in Nottingham, he moved to the University of Southampton’s faculty of medicine, where he spent a couple of years as a research fellow before helping to set up a laboratory for the Isle of Wight Birth Cohort, a longitudinal study that investigates allergies. “I changed field again to asthma and allergy,” he says.

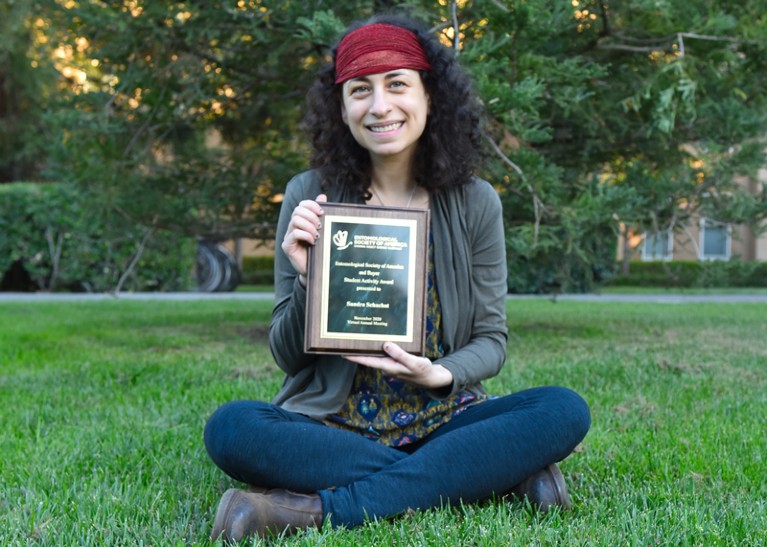

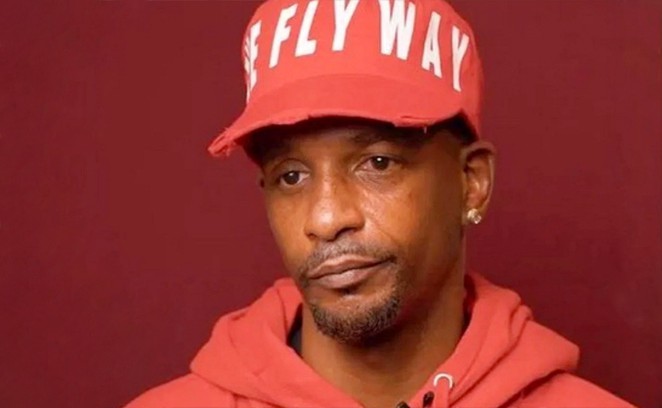

Aref Kyyaly appreciates the inclusivity of UK society.Credit: Sami Sultan

None of this chopping and changing of jobs and locations was for CV-building purposes. Kyyaly says he hasn’t really had the luxury of thinking about his career trajectory. If there was a gap in his employment, he would run the risk of having his visa revoked, in which case he’d need to either return to Syria or apply for asylum. So, he was often forced to jump from one post to another when academic funding ran out or looked unstable.

Eventually, things caught up with him: his Syrian passport was about to expire and, to keep his UK work visa, he would have had to return to Syria to renew his passport. This forced Kyyaly’s hand, and he applied for asylum in the United Kingdom.

It took two-and-a-half years for the UK government to reach a decision to allow him to stay as an asylum seeker, he says. That’s fairly typical of the UK asylum system; a 2021 report from the Refugee Council, a UK charity, found that the number of people waiting more than a year for an initial decision on their asylum claim rose from 3,588 in 2010 to 33,016 in 2020.

Podcast: Dodging snipers, fleeing war: displaced researchers share their stories

Kyyaly is now a lecturer in biomedical science at Solent University in Southampton, UK. He spends most of his time teaching, but he is also investigating molecular biomarkers for complicated and difficult-to-diagnose diseases and conditions, such as cancers and allergies.

It’s a job he enjoys and most importantly, he says, it’s a permanent role. But when he looks back at his career history, he sees how his immigration status and the geopolitics of the Middle East severely limited his options. If he had been able to secure a permanent job when he arrived in the United Kingdom, he thinks his current salary would have reached at least £70,000 (US$87,000). “I’m on half of that now,” he says. “I have friends who started four or five years after me and now they’re way ahead of me.”

But it’s about more than money. “If you are doing research in one topic for eight years, then you’re an expert,” he says. “But if you’re changing every two years, yes, you have a broader range of skills and things, but if you’re applying for funding or for jobs, then you’re not that attractive.”

But this is where Kyyaly’s “guiding principle” comes into play.

“If you’re passionate about research, about science, I think my advice is to never give up. I was about to give up in 2013 before I reached out to Cara because everything felt closed to me,” he says. Now he has a job he loves; his children are enjoying school in the United Kingdom; and he and his wife feel accepted into British society. It’s been years since he last saw his parents but he’s hoping in the near future to be able to meet them once again.

“If you have to change fields, change fields. Change jobs if you must. Keep moving. Keep your dream in your mind until you have the chance to get it out into the real world.”

That mentality, Kyyaly says, has allowed him to keep his dignity and a sense of agency through very tough times. “You can’t change life to follow you. You need to follow life. It’s very similar to sailing. You cannot control the wind, but you can control the sail.”

[ad_2]

Source Article Link