[ad_1]

Credit: Chiara Zarmati

On a visit to a woman at home in rural Zambia, community-health worker Janet Chisaila unpacks a bag that contains swabs, sample pots and a 3D-printed model of a vagina and cervix. Using the model, Chisaila explains how to use the swabs to take genital samples. The woman then goes to a private area to do her sampling. Later, she visits the local health clinic, where Chisaila’s colleague Alice Mwale, a nurse, takes digital photographs of the woman’s cervix, which are then uploaded to a secure platform. Thousands of miles away, at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, clinician and principal investigator Amaya Bustinduy logs in to the platform to review the images and offer advice.

Part of Nature Outlook: Neglected tropical diseases

The woman is one of around 2,500 taking part in a study1 called Zipime Weka Schista! (Do self-testing, sister!), which aims to transform the diagnosis of a little-known neglected tropical disease (NTD) called female genital schistosomiasis (FGS). By combining FGS screening with testing for HIV, human papillomavirus (HPV) and a sexually transmitted disease called trichomoniasis in a single visit, the tests are striking a blow for gender equality and women’s sexual- and reproductive-health rights. “This approach has empowered the women to know about these diseases,” says Chisaila. “They have been given the confidence to talk about some of these health issues and have access to treatment and care.”

FGS is a debilitating gynaecological condition caused by chronic infection with a parasitic disease known as schistosomiasis. Painful and stigmatizing, the disease is associated with reduced fertility and miscarriage. Infection increases the risk of contracting HIV, and probably HPV and cervical cancer as well. Although it was first recorded2 125 years ago, few people — even health-care workers in regions where the condition is thought to be most common — are aware that it exists. “FGS is neglected, under-researched and overlooked in endemic countries,” says Kwame Shanaube, clinical epidemiologist and site coordinator of the Zipime Weka Schista! study at Zambart, a Zambian non-governmental public-health research organization in Lusaka that specializes in public health and grew out of a collaboration between the University of Zambia’s School of Medicine and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

Women and girls are vulnerable to FGS both because of their sex and because of socially determined roles and expectations that increase their exposure to infection and make it difficult for them to access treatment or talk about their symptoms. The social roles of women expose them more often to infection, and make it harder to access prevention and treatment, or even to talk about their symptoms than do those of men. “It’s very hard for women to talk about painful sex and sub-fertility in contexts where it’s hard to access a health-care provider,” says Sally Theobald at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, UK, who studies gender inequity and health systems. “So it is this chronic pain and rights issues that have been going on for decades and decades.”

FGS is a disease of compounded neglect: ignored because it is an illness found mainly in low-income countries; overlooked because of a lack of awareness; stigmatized because it pertains to sexual health; and further neglected because it affects women, especially low-income and marginalized women, whose health is chronically underfunded and under-researched. Tackling it is therefore not merely a biomedical problem, but also one that involves addressing gender inequality and the sexual and reproductive health rights of women and girls.

An insidious disease

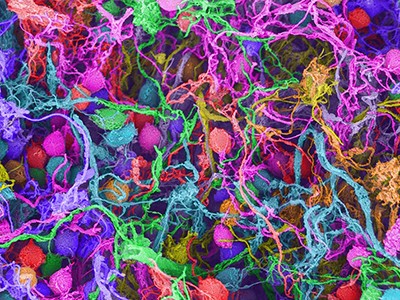

Schistosomiasis, also called bilharzia, is caused by parasitic worms known as schistosomes. The species that causes FGS, Schistosoma haematobium, infests freshwater lakes and rivers. The larvae burrow through a person’s skin, making their way to a collection of veins around the bladder and pelvic organs. There, the larvae mature into adults, each the size of a grain of rice, and mate. Each female worm lays hundreds of eggs. These work their way through the bladder wall with the aid of sharp spines and destructive enzymes. Once in the bladder, the eggs are released through urination into the environment to start the cycle anew.

In some societies, girls are expected to fetch the family’s water.Credit: Simon Townsley/Panos Pictures

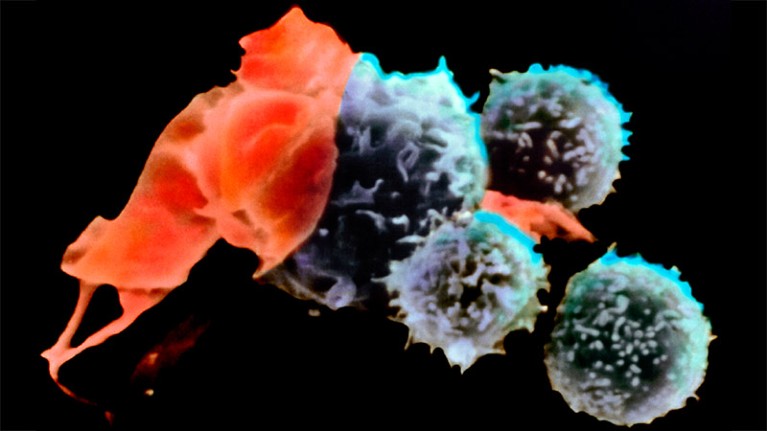

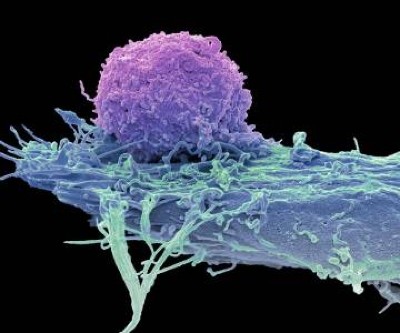

Left untreated, the infection becomes chronic. “These worms can live in your bloodstream for 30 or 40 years,” says Evan Secor, a parasitologist at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, Georgia. Between 30% and 75% of women infected with S. haematobium go on to develop FGS, which occurs when schistosome eggs end up trapped in the tissues of the reproductive system, including the cervix, vagina and fallopian tubes. These trapped eggs cause pain and become surrounded by immune cells, forming inflamed nodules called granulomas, which in turn can lead to scarring. Men can also get genital schistosomiasis, particularly those whose occupations put them at increased risk, such as freshwater fishermen.

Only about 15,000 women and girls in endemic areas have been included in study surveys for FGS, so there are no precise figures for the prevalence of the condition, says Bustinduy. Estimates suggest that between 30 million and 56 million women globally have FGS, most of them in sub-Saharan Africa.

Part of the problem lies in the difficulty of diagnosing the disease. Conventional approaches involve inspecting the cervix with an instrument known as a colposcope, or taking a biopsy and sending it to a lab to look for schistosome eggs under a microscope. But these tools are rarely available in endemic areas — colposcopes are expensive and require specialized gynaecological training to use.

Looking for schistosome eggs in urine samples is cheap, but misses most FGS cases because the correlation between eggs in urine and FGS is only about 20–30% . Molecular testing to detect schistosome DNA in samples such as urine is much more reliable but requires specialist facilities and expensive reagents. Facilities such as these are also usually found only in hospitals, which can be hard for people with low incomes to travel to. And gynaecological examination of girls and young women before they are sexually active is unacceptable in some cultures.

Diagnostic delays mean that, even after standard treatment with a drug called praziquantel that kills the adult worms, women can have permanent tissue damage. Delphine Pedeboy-Knoetze, who grew up in France but who now lives and works in South Africa, had FGS that went undiagnosed for several months. She still experiences chronic pain six years later. “It’s extremely demoralizing, because nobody can establish what’s wrong,” she says. Consultations with multiple specialists in various countries have yielded no answers. This adds to the mental-health burden of FGS. “It’s the loneliness of it,” she says. “That’s the scariest feeling, because you think, ‘Oh wow, I really am on my own’.”

An array of neglect

The astonishing lack of awareness of FGS among health workers starts with education. FGS is not mentioned in many medical textbooks and rarely forms part of medical training. The classic symptom of urogenital schistosomiasis is blood in the urine, which can be confused with menstruation or ‘spotting’. This means that the disease is assumed to affect men only. “Health professionals do not have FGS in their radar of diagnosis,” says Motto Nganda, a clinician at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine who has studied how to integrate FGS management into primary health-care settings in Liberia.

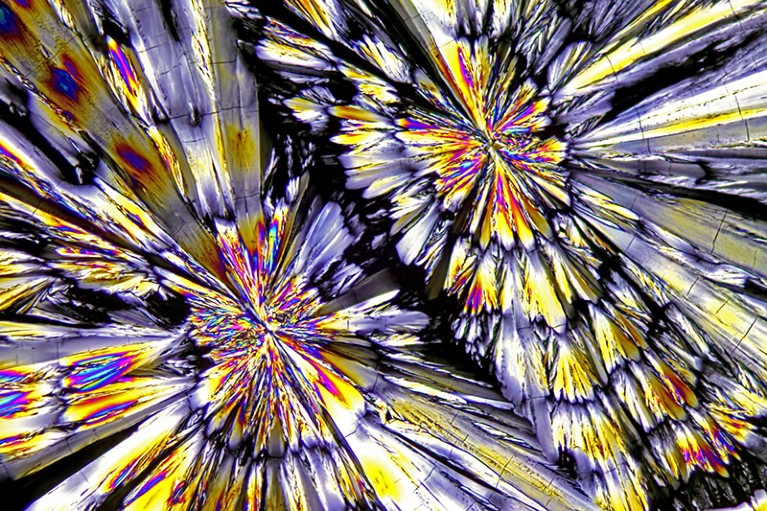

Schistosoma larvae can burrow through a person’s skin.Credit: LENNART NILSSON, TT/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

This means that genital symptoms can be wrongly attributed to sexually-transmitted infections, with the result that women are not only given ineffective treatment, but also stigmatized. Teenage girls report being scolded by clinic nurses who assume that the girls have had premarital sex, while older women (or their partners) have been accused of infidelity. Pedeboy-Knoetze, for example, was told that she had herpes and to be suspicious of her partner.

Larger political decisions have also shaped the neglect of FGS, says Laura Dean, who studies person-centred health-system responses to NTDs at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine. Mass drug-administration is the main effort to control NTDs that can be tackled in this way, including schistosomiasis, she says. The approach is designed to prevent and treat these diseases in endemic areas. This is an essential strategy and one that should be continued, Dean says. However, it isn’t a magic bullet that, in isolation, can prevent continuous cycles of reinfection — particularly for a disease such as schistosomiasis that is closely linked to the broader environment and access to clean water, sanitation and hygiene. People who cannot access these programmes, or for whom the drugs don’t work, can develop chronic morbidities. This risk is especially high for diseases such as schistosomiasis in which there is a high risk of reinfection3.

Compounding all of these factors is gender: the social expectations and roles that societies attribute to men and women (and people of other genders). Gender is increasingly being recognized as a key factor that affects an individual’s vulnerability to NTDs, and FGS is a classic example. “Gender norms in many contexts mean that much of the work done by women in households and communities involves a lot of interaction with water,” says Theobald. This includes doing the family’s laundry and fetching water from local rivers and ponds. “So there’s ongoing exposure to schistosomiasis in multiple ways.”

Gender also affects access to treatment and health care. For schistosomiasis, this involves the mass administration of praziquantel in vulnerable populations4. This is often delivered to children in schools, but girls are less likely to attend school than are boys, says Secor. Gender inequality also affects how women experience the disease once they have it. “It brings subfertility, it brings painful sex, it brings discharge, and it’s in a context where there’s so much pressure to conceive,” says Theobald. For example, in some parts of Liberia and Nigeria, a woman’s social status is linked to fertility and her ability to have children. As a result of poor sexual and reproductive health, including pregnancy complications or infertility, women with FGS can be ostracized, accused of witchcraft, and faced with the loss of their homes and partners5.

“The fact that there’s a parasite that’s easily treatable with a dose of praziquantel that costs very little and that can change the outcome of a woman’s life, and we’re not doing that, is absolutely shocking,” says Pedeboy-Knoetze. “Shame on the global-health community and shame on the medical community for this.”

Attack on all fronts

All of this means that programmes to tackle FGS need to build in social, political and cultural factors, as well as biomedical ones. They also need to work with the clinical resources that are available in endemic areas. In the past few years, a number of projects have piloted ways to do this. The Zipime Weka Schista! study, for example, uses culturally appropriate ways to raise awareness of FGS. Drama groups perform songs and dances in areas such as community marketplaces to draw in members of the public and communicate messages about FGS. Community workers then go door to door to offer more information and to recruit study participants.

A health worker at a medical centre in Zimbabwe tests for schistosome parasites.Credit: Xinhua/Shutterstock

Reactions from the communities have been positive, says Rhoda Ndubani, a social scientist and study manager of Zipime Weka Schista! at Zambart. The project is reducing stigma around these diseases and giving women the confidence to talk about them and seek treatment, she adds. It’s also empowering the nurses and community midwives. “It’s really helping us because, before, I did not know that women can actually get schistosomiasis,” says Mwale. Training and handheld colposcopes are already allowing nurses to make FGS diagnoses independently and to administer praziquantel immediately.

Similar messages came out of a study in Liberia. Nganda, Dean and their colleagues piloted a clinical-care package in primary-care settings, which included an FGS symptoms checklist, training in simple gynaecological examinations and treatment guides. Importantly, the package included training traditional midwives, who are trusted in local communities. The study diagnosed and treated 245 women and girls over a period of 6 months, during routine primary health care6. A related study5 in Nigeria returned similar findings. “It’s showing what is possible to do within different under-resourced health systems,” says Theobald.

Making diagnoses in primary-care settings that are accessible to women is key. “We’re trying to steer away from using hospitals as much as possible, because that is really when the bottleneck comes in,” says Bustinduy. The goal, she says, is to instead promote the use of rural clinics staffed with midwives and nurses. It’s also about making the FGS diagnosis less reliant on clinical examinations, which can result in varying diagnoses depending on the physicians, adds Secor, who chairs a World Health Organization diagnostic advisory panel for FGS diagnostics. “We’re really trying to move to something that’s a little bit more objective,” he says.

Taking inspiration from other self-sampling programmes, such as those in place for HPV and HIV, Bustinduy and her colleagues conducted a study of around 600 women to explore the use of self-sampled genital swabs and DNA testing7. The BILHIV (bilharzia and HIV) study showed that participants readily accepted self-sampling, that it was as good as clinical sampling at detecting FGS, and, therefore, that home-based self-sampling could present a scalable way of diagnosing FGS in endemic regions. In further experiments, the BILHIV study investigated a lower cost alternative to the DNA-amplifying technique PCR called recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA). Unlike PCR, RPA works at room temperature, and is rapid and highly portable. The findings suggested that RPA was a viable alternative to PCR, and could form part of a portable laboratory to be used at point of care8.

FGS is associated with other genital infections, such as HIV, HPV (the main cause of cervical cancer) and trichomoniasis. The Zipime Weka Schista! study therefore aims to see whether testing for all four could be integrated into a single home visit. Like the BILHIV study, the approach is getting a positive reaction from women — especially the self-sampling aspect. “For many, it is the first time they have been screened in this way,” says Chisaila.

Scaling up

There are signs that the condition is slowly starting to shed its neglected status: its association with HIV has brought the sexual and reproductive health communities together, and advocacy by FGS researchers is moving the issue up national and international health agendas. In January, for example, a government committee report recommended that FGS be integrated into the UK government’s sexual and reproductive rights aid programmes. Witnesses testifying to the committee advocated moving away from a focus on individual diseases to a patient-centred one — FGS often falls into a gap between NTD and sexual-health programmes. The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS has also recognized the need for FGS integration.

Science has its part to play, too. One aspect is in finding ways to help women like Pedeboy-Knoetze who have tissue damage. “We don’t really have a good way to treat that chronic, longer, more severe pathology,” says Secor. Another is finding ways to prevent the disease, such as vaccination. Adding these to mass drug-administration programmes could reduce the risk of reinfection and help to cut the cycle of transmission. Three vaccines are currently undergoing development. Although each targets the Schistosoma mansoni parasite, which causes intestinal schistosomiasis, one of them also protects against S. haematobium. This vaccine, called Sm-p80 (SchistoShield), is in phase I trials.

More diagnostics are also in the works. DNA swabs are thought not to work well in advanced FGS, because the eggs are walled inside scar tissue, so researchers are exploring two other approaches. One is a test for schistosome antigens in the blood that is scheduled to go into field trials in the next few months, says Secor. Another approach, one Secor’s team is taking, is testing for anti-schistosome antibodies. Although these don’t necessarily reveal whether a person has an active infection (antibodies persist for a long time), such tests could be easy to incorporate into routine clinical screening, such as prenatal visits. Tests under development include lateral-flow tests similar to pregnancy tests or those used to rapidly detect COVID-19 (ref. 9). These tests can detect antibodies or schistosome antigens and are easy for users to interpret, and would ideally cost less than US$1 per test, says Secor. “I’m optimistic,” he says, “but we’re not there yet.”

Complicating matters is that any new approaches to diagnosing and treating FGS must be adapted to the realities of living in some of the poorest, most marginalized communities in the world. “If we can do that, it’s a win–win for gender equity, rights and social justice,” says Theobald. “It’s a win–win for responsive, effective, person-centred health systems.”

[ad_2]

Source Article Link