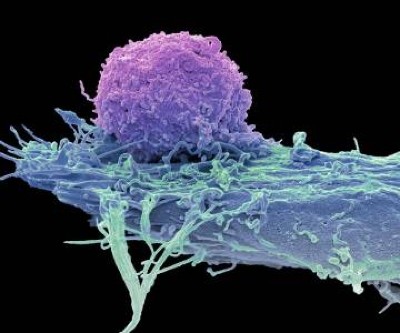

T cells (blue; artificially coloured) attack a cancer cell (red).Credit: BSIP Lecaque/Science Photo Library

More than 35 years after it was invented, a therapy that uses immune cells extracted from a person’s own tumour is finally hitting the clinic. At least 20 people with advanced melanoma have embarked on treatment with what are called tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), which target and kill cancer cells.

The regimen, called lifileucel, is the first TIL therapy to be approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). And it is the first immune-cell therapy to win FDA approval for treating solid tumours such as melanoma. Doctors already deploy immune cells called CAR (chimeric antigen receptor) T cells to treat cancer, but CAR-T therapy is used against only blood cancers such as leukaemia.

Cancer-fighting CAR-T cells could be made inside body with viral injection

TILs are a type of naturally occurring immune cell called a T cell. TILs recognize targets, called antigens, on the surfaces of cancer cells and burrow into solid tumours to kill them. They are the brainchild of Steven Rosenberg, a cancer researcher and surgeon at the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, Maryland, who first showed1 that TILs could shrink tumours in people with melanoma. In clinical trials, TIL treatment has put some people with melanoma in remission for up to 20 years.

The FDA granted approval on 16 February to lifileucel, sold as Amtagvi by biotechnology company Iovance Biotherapeutics, based in San Carlos, California. The approval “is a great accomplishment”, says TIL specialist Nick Restifo, chief scientist at Marble Therapeutics in Boston, Massachusetts. He says that it will pave the way for TILs to be used to treat other cancers, including lung and pancreatic tumours, in the near future.

Nature spoke with scientists about TIL therapy and its future.

How are TILs made and used?

After a person’s tumour is removed, surgeons send tissue samples to a laboratory that isolates TILs from them and grow the TILs for three weeks until they’ve multiplied into billions of cells. Before the TILs are reinfused back into the treated person, the recipient is given chemotherapy and an immune chemical called interleukin-2 (IL-2) that temporarily kills immune cells to make room for the TILs.

Turbocharged CAR-T cells melt tumours in mice — using a trick from cancer cells

For now, lifileucel can be used only as a last-line treatment in people with certain forms of advanced melanoma that haven’t responded to other treatments. But Iovance and others are currently testing lifileucel as a first-line treatment against melanoma. Some evidence suggests that it might be even more effective as a first- or second-line treatment, before an aggressive treatment can harm the TILs in tumours.

How effective are TILs?

In Iovance’s trial testing lifileucel in 153 people with melanoma, tumours shrank in 31% of the participants2. And in a second trial in Denmark, 20% of people who received TIL therapy went into complete remission, compared with 7% of those who received a different drug3.

Amod Sarnaik, a surgical oncologist at the Moffitt Center in Tampa, Florida, who led Iovance’s trial, says that solid tumours can generally become resistant to treatments such as chemotherapy. But removing most of the tumour and infusing billions of TILs is often enough “brute force” to overcome the cancer, Sarnaik says. The immune system then ‘remembers’ the most effective TILs, allowing it to quickly churn them out if the cancer comes back.

What are the side effects?

Most of the therapy’s side effects, such as anaemia and fevers, come from the chemotherapy and IL-2 treatments used to prepare patients for TIL infusion. But Sarnaik says that there is a risk of “friendly fire” if TILs also attack normal cells alongside the tumour cells. This can cause autoimmune conditions such as vitiligo, in which TILs cause skin discolouration by attacking pigment cells.

How are TILs regulated?

Similar to CAR T cells, TILs are naturally occurring cells that are specific to each person. But whereas CAR T cells are genetically engineered to attack specific antigens on cancer cells, no one knows which antigens any particular person’s TILs target — although it largely doesn’t matter, as long as they work for the individual person. “It’s a different drug literally for every patient,” Restifo says.

Because it’s impossible for the FDA to assess every patient’s set of TILs, the agency instead approved the process that Iovance uses to multiply the cells and the way that they are administered to people with cancer. And because TILs occur naturally, companies can patent only their processes and not the cells overall. “It’s good news for all of us trying to develop different ways of improving on the process,” Sarnaik says.

How much will the treatment cost?

Iovance has said that it plans to charge US$515,000 for the treatment, making it even more expensive than some of the six CAR-T therapies approved in the United States.

Health-care inequality could deepen with precision oncology

But other approaches might make TILs more affordable, says Inge Marie Svane, a cancer immunologist at Copenhagen University Hospital who is running TIL trials in Europe. Several university hospitals are growing TILs for melanoma without a company’s involvement, using a process that costs about €50,000 (US$55,000).

What’s next for TILs?

Dozens of companies are developing TILs for other types of tumours, and some have already proven effective against cervical4 and lung5 cancer. Researchers are developing improvements such as genetic manipulations that make TILs better at infiltrating and killing tumours. Svane, for instance, is about to start a clinical trial of TILs that are missing a gene that allows cancerous cells to kill them. “What we want to achieve is complete remission,” she says.