Last week, Harvard University researchers announced the cancellation of a high-profile solar geoengineering experiment, frustrating the project’s supporters. But advocates say that all is not lost, and that momentum for evaluating ways to artificially cool the planet is building internationally.

First sun-dimming experiment will test a way to cool Earth

The study, called the Stratospheric Controlled Perturbation Experiment (SCoPEx), was to be the first to systematically inject particles into Earth’s upper atmosphere and then measure whether they could safely reflect sunlight back into space. Worried about the lacklustre progress by governments to curb greenhouse-gas emissions, advocates for SCoPEx say that such tests are necessary to determine whether solar geoengineering might one day provide emergency relief from the worst impacts of uncontrolled climate change.

But the project faced opposition from those concerned about unintended and potentially global consequences. Critics, including many academics, say that solar engineering is too risky and could reduce pressure on world leaders to eliminate greenhouse-gas emissions by offering a ‘plan B’.

“I’m saddened but not surprised to see it cancelled,” says Peter Frumhoff, a climatologist at Harvard in Cambridge, Massachusetts, who helped to organize a scientific advisory panel for the project. Harvard’s status as an elite research institution also fuelled fears that powerful Western players might unilaterally develop the technology, even though it could have global effects. Frumhoff says that what’s needed is some kind of international consensus on solar geoengineering. “No one seems to be able to agree at the moment about whether and how research should go forward in a way that would have legitimacy.”

Nature talks to scientists about the controversy, as well as about ongoing efforts to push forward with research.

Why did Harvard cancel the experiment?

The plan for SCoPEx was to launch a high-altitude balloon into the stratosphere, which extends some 10–50 kilometres above Earth’s surface. The balloon would release up to 2 kilograms of calcium carbonate particles — an ingredient in over-the-counter antacids — and then measure their dispersal, their interaction with other chemicals in the stratosphere and, ultimately, their ability to reflect sunlight.

Harvard creates advisory panel to oversee solar geoengineering project

The team never made it that far: the first launch, intended as an equipment test and set to take place at the Esrange Space Centre in northern Sweden, was called off in 2021 when environmentalists and local Indigenous groups announced their opposition. This was after the Harvard team had spent more than a year working with its advisory committee to address concerns about the project, which remained in limbo until last week’s announcement.

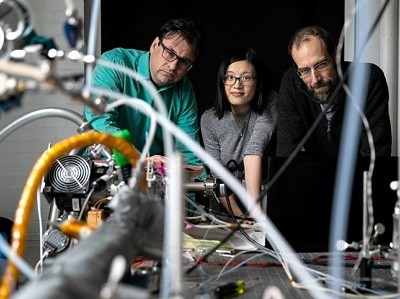

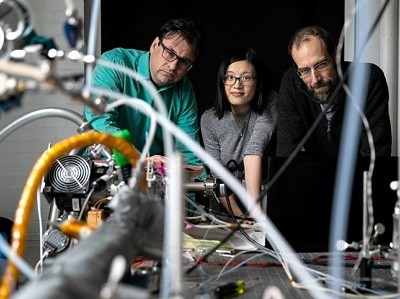

SCoPEx principal investigator Frank Keutsch, an atmospheric chemist at Harvard, did not respond to interview requests from Nature, but told MIT Technology Review that he wants to pursue “other innovative research avenues” in solar geoengineering. Another project leader, experimental physicist David Keith, told Nature the project struggled both with intense media attention and with how to address calls from the scientific advisory committee to broadly and formally engage with the public.

“We just didn’t see a way to square that circle and make it happen,” says Keith, who left Harvard last year to set up a new climate engineering programme at the University of Chicago in Illinois.

Is any research in solar geoengineering happening now?

Scientific organizations such as the UK Royal Society and the US National Academy of Sciences have long called for solar geoengineering research, and scientists have done extensive computer modelling. Some have even conducted field experiments to see whether they could brighten low-lying clouds to cool the local climate. But conducting experiments in the stratosphere, where injected particles invariably cross international borders, has proved challenging, as the Harvard case shows.

Can artificially altered clouds save the Great Barrier Reef?

Some have moved forwards anyway, with little or no oversight.

An independent researcher in the United Kingdom, Andrew Lockley, says he launched a low-cost balloon that released 400 grams of sulfur dioxide into the stratosphere in 2022 and is now trying to publish his results. A for-profit company called Make Sunsets, based in Box Elder, South Dakota, says it has also begun dispersing sulfur dioxide into the stratosphere by balloon. Backed by venture capitalists and criticized by scientists, the company is selling ‘cooling credits’ that allegedly offset one tonne of carbon-dioxide emissions for US$10 each, or $1 each with a monthly subscription.

The US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), meanwhile, has begun gathering background data from the stratosphere to better understand — and detect — potential solar geoengineering efforts in future, both overt and covert. An initial aircraft survey above the Arctic last year showed1 that rocket launches and falling satellite debris have left particles of aluminium, copper and various exotic metals in the stratosphere with as-yet-unknown consequences.

Launched in 2020, the programme is funded to the tune of US$9.5 million this year, and at the request of the US Congress, NOAA is currently preparing a plan for future geoengineering research. For now, the goal is to gather the background data that scientists need to test their theoretical models, says David Fahey, an atmospheric scientist who is leading the effort at NOAA. “That is ultimately the way we’re going to evaluate the feasibility and the consequences.”

So what’s next?

It’s unclear, but scientists say that discussions about solar geoengineering aren’t going away.

Just last month, countries at the United Nations Environment Assembly failed to approve — for the second time in five years — a proposal calling for a formal assessment of the technology. That proposal might have hit a wall owing to differences of opinion about how to proceed, as well as concerns about legitimizing the technology, but it also showed that the conversation is expanding internationally, says Shuchi Talati, an environmental engineer who served on the SCoPEx advisory committee and, last year, founded the Alliance for Just Deliberation on Solar Geoengineering in Washington DC.

US urged to invest in sun-dimming studies as climate warms

“For better or worse, momentum is growing in this space,” says Talati, whose organization is working to bring governments and civil-society organizations across low- and middle-income countries up to speed on the issue.

Also last month, the World Climate Research Programme, which helps to coordinate climate science globally, launched an initiative to promote research into climate interventions such as solar geoengineering. That work is just beginning, but the goal is to clarify priorities and lay out a global research agenda, says Daniele Visioni, a climate scientist at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, who is co-chairing the effort.

For his part, Keith is now working with the University of Chicago to build what might be the world’s largest academic initiative focused on climate engineering. The university is now looking to hire ten full-time faculty members to probe technologies ranging from solar geoengineering to carbon removal.

Going forwards, Keith says it’s appropriate to seek broad public input, particularly when there are potential harms that might arise from an experiment. He isn’t convinced, however, that such processes are necessary for small experiments that are not expected to impact the environment and that follow the usual rules and regulations.

“I don’t believe we need some kind of global process for those experiments,” Keith says.