[ad_1]

A person has received an experimental treatment for the first time that, if successful, will lead them to grow an additional, ‘miniature liver’. The procedure, developed by the biotechnology firm LyGenesis, marks the beginning of a clinical trial designed for people whose livers are failing, but who have not received an organ transplant.

First pig liver transplanted into a person lasts for 10 days

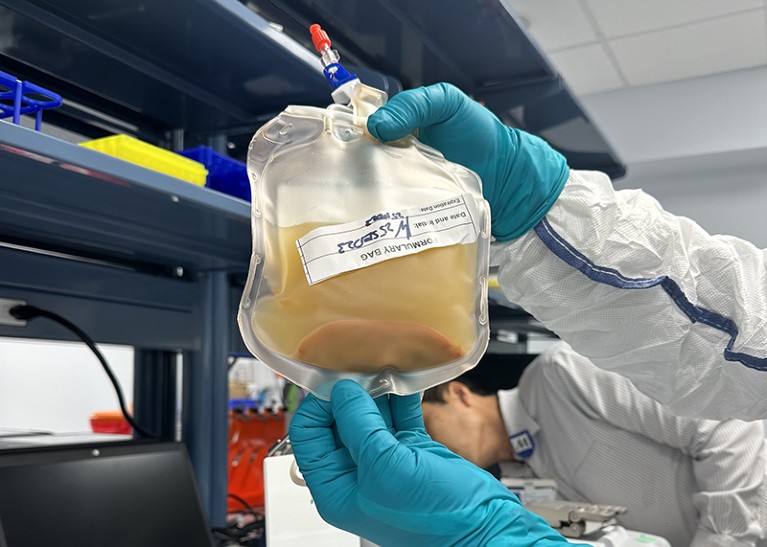

The approach is unusual: researchers injected healthy liver cells from a donor into a lymph node in the upper abdomen of the person with liver failure. The idea is that in several months, the cells will multiply and take over the lymph node to form a structure that can perform the blood-filtering duties of the person’s failing liver.

“It’s a very bold and incredibly innovative idea,” says Valerie Gouon-Evans, a liver-regeneration specialist at Boston University in Massachusetts, who is not involved with the company.

The person who received the treatment, on 25 March, is recovering well from the procedure and was discharged from the clinic, says Michael Hufford, chief executive of LyGenesis, which is based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. But physicians will need to closely monitor them for infection because the person needs to take immunosuppressive drugs so that their body doesn’t reject the donor cells, says Stuart Forbes, a hepatologist at the University of Edinburgh, UK, who is not affiliated with LyGenesis.

Organ crisis

More than 50,000 people in the United States die each year with liver disease. In the end stage of the disease, scar tissue that has accumulated prevents the organ from filtering toxic substances in the blood, and can lead to infection or liver cancer.

A liver transplant can help, but there is a shortage of organs: about 1,000 people in the United States die every year waiting for a transplant. Thousands more aren’t eligible because they are too ill to undergo the procedure.

A person received donor liver cells on 25 March that were injected into one of their lymph nodes.Credit: LyGenesis

LyGenesis has been trialling an approach that could help people in this situation — and make use of donated livers that would otherwise go to waste because a person on the transplant waiting list with a compatible health profile hasn’t materialized in time. The company’s strategy delivers the donor cells through a tube in the throat, injecting them into a lymph node near the liver. Lymph nodes, which also filter waste in the body and are an important part of the immune system, are ideal for growing mini livers, Hufford says, because they receive a large supply of blood and there are hundreds of them throughout the body, so if a few are used to generate mini livers, plenty of others can continue to function as lymph nodes.

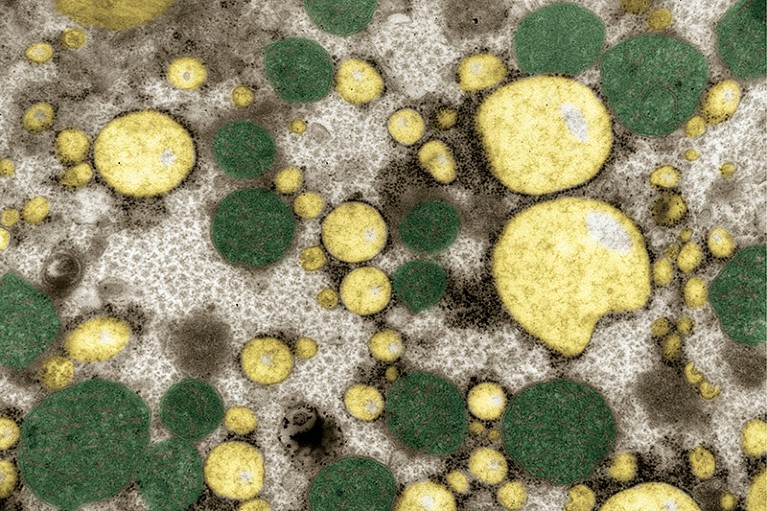

The treatment has so far worked in mice1, dogs and pigs2. To test the therapy in pigs, researchers restricted blood flow to the animals’ livers, causing the organs to fail, and injected donor cells into lymph nodes. Miniature livers formed within two months and had a cellular architecture resembling a healthy liver. Researchers even found cells that transport bile, a digestive fluid produced by the liver, in the mini livers of the pigs. In this case, they saw no build-up of bile acid, suggesting that the mini organs were processing the fluid.

Hufford says there’s reason to think that the organs won’t grow indefinitely in the lymph nodes. The mini organs rely on chemical distress signals from the failing liver to grow; once the new organs have stabilized blood filtering, they will stop growing because that distress signal disappears, he says. But it’s not yet clear precisely how large the mini-livers will become in humans, he adds.

The company aims to enrol 12 people into the phase II trial by mid-2025 and publish results the following year, Hufford says. The trial, which was approved by US regulators in 2020, will not only measure participant safety, survival time and quality of life post-treatment, but will also help to establish the ideal number of mini livers to stabilize someone’s health. The clinicians running the trial will inject liver cells in up to five of a person’s lymph nodes to determine whether the extra organs can boost the procedure’s success rate.

A stop-gap measure

However, mini livers might not relieve all of the complications of end-stage liver disease, says Forbes, who has formed his own company to tackle liver disease using genetically modified immune cells that stimulate repair. One of the most serious of these is portal hypertension, in which the build-up of scar tissue compresses blood vessels in the liver and can cause internal bleeding.

Pig brains kept alive outside body for hours after death

Hufford acknowledges that the mini livers are not expected to address portal hypertension, but the hope is that they can provide a stopgap until a liver becomes available for transplant, or make people healthy enough to undergo a transplant. “That would be amazing, because these patients currently have no other treatment options,” Gouon-Evans says.

LyGenesis has ambitions beyond mini livers, too. The company is now testing similar approaches to grow kidney and pancreas cells in the lymph nodes of animals, Hufford says.

If the liver trial is successful, Gouon-Evans says, it would be worth investigating whether a person’s own stem cells could be used to generate the cells that seed the lymph nodes. This technique could create personalized cells that capture the diversity of cells in the liver and don’t require immunosuppressive drugs, she says.

[ad_2]

Source Article Link