[ad_1]

Far north of the Arctic Circle lies a fjord on the front lines of climate change. Geir Wing Gabrielsen has been visiting this inlet, located on the northwest side of the Norwegian archipelago Svalbard, since 1981, when he first came to study the behaviour of Arctic birds. It used to be that each year when the ecotoxicologist would arrive in May or June — springtime in Svalbard — he could count on one thing: that the fjord would still be locked in ice.

But all of that has changed.

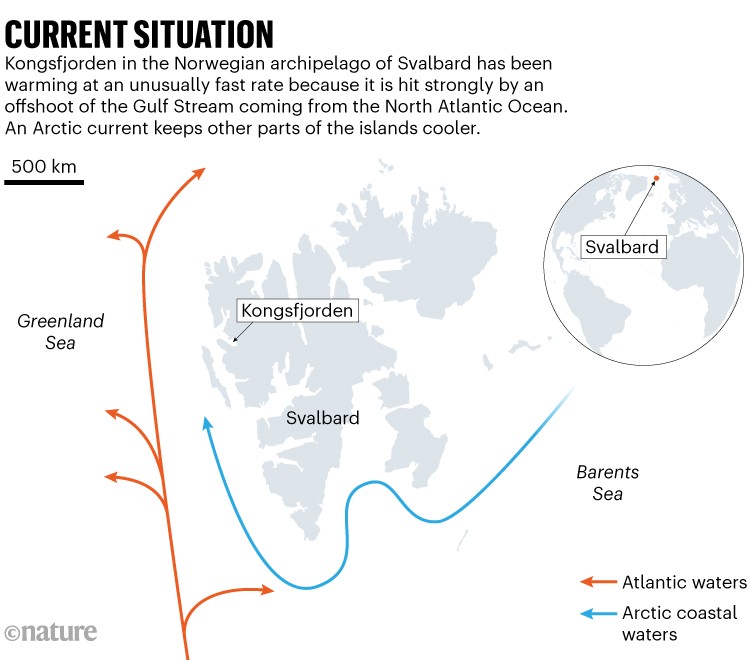

The Arctic is warming four times as fast as the rest of the world owing to climate change. And because of a quirk of ocean currents, the fjord, called Kongsfjorden, is warming even faster (see ‘Current situation’). So much so that, since 2006, it no longer freezes over — even when the Sun sets during the winter months, between October and February.

Source: Buchholz, F., Buchholz, C. M. & Weslawski, J. M. Polar Biol. 33. 101–113 (2009).

This has completely reshaped the fjord’s ecosystem, according to a study in Polish Polar Research published in January1. Arctic mammals such as beluga whales (Delphinapterus leucas) and ringed seals (Phoca hispida) that once called the fjord home have left. Meanwhile, more southerly animals including Atlantic puffins (Fratercula arctica) and Atlantic mackerels (Scomber scombrus) have moved in. And new habitats have popped up along the shoreline where sea ice once suffocated plant growth.

For researchers such as Gabrielsen, at the University Centre in Svalbard, these changes are met with a sense of loss. But they are also viewed as an opportunity. The fjord “will provide information about how the Arctic will be in the future”, Gabrielsen says. And it could help to answer the big questions of which species will survive the shifting climate in the Arctic, and how.

“It’s incredible that I — in my time — have been able to see such dramatic changes,” he says.

As shown in this photo from April 2005, Kongsfjorden used to freeze over enough during springtime for students and researchers to safely walk on it.Credit: Kim Holmén

Vanishing Ice

Kongsfjorden, meaning ‘king’s fjord’, is arguably the best-studied Arctic fjord in the world. Norway established its first Arctic research station there in the 1960s in what was then the mining community of Ny-Ålesund. Since then, 11 other nations, including Germany, China and India, have set up camp there.

The density of research activity in the fjord has made it possible to track its environmental changes in detail. The eastern reach of Svalbard is pummeled by an Arctic current that keeps its frigid temperatures stable. Meanwhile, the western reach — where Kongsfjorden sits — is exposed to an offshoot of the Atlantic Gulf Stream. As a result, the fjord’s winter water temperature rose from 0.3 ºC in 2004 to 4 ºC in 2017. The most obvious effect of the warmer water hitting Kongsfjorden is the rapid retreat of its glaciers, says Kai Bischof, a marine biologist at the University of Bremen in Germany.

A view of Ny-Ålesund from April 2023 showing the fjord free of sea ice.Credit: Lisi Niesner/Reuters

“If you go there, like me, every other year, you can really see the changes,” Bischof adds. He remembers how, in the 1990s, a retreating glacier revealed a surprise: a piece of land once covered in ice and marked on maps as a peninsula turned out to be an island. Scientists can now comfortably motor around it in boats. “The rate of change is accelerating,” Bischof says.

Out with the old, in with the new

Kongsfjorden has become something of a pilgrimage for politicians seeking to understand global warming. Both former UN secretary general Ban Ki-Moon and former US secretary of state John Kerry have toured the fjord. The rapidly changing landscape makes it “a place where you can really experience the changing climate through your eyes”, says Bischof.

The fjord has already taught researchers that the Arctic is susceptible to tipping points. When it failed to ice over in 2006, it “was a great wake-up call”, Gabrielsen says.

But determining how exactly climate change will scramble the fjord’s ecosystem is a bit more difficult.

Researchers have so far recorded the effects on some species. For instance, ringed seals have mostly left the fjord because, without any sea ice in which to build their dens during the spring, their pups were exposed to predatory birds. In 2023, scientists recording the living symphony of the fjord also noted that the frequency of whale songs had diminished, compared with Svalbard’s northeast coast2.

Black-legged kittiwakes feed in Kongsfjorden.Credit: Geir Wing Gabrielsen

Meanwhile, some opportunistic species have moved onto the scene. Atlantic mackerels were first spotted in September 2013. The Atlantic puffin, spotted occasionally in the 1980s, is now thriving in Kongsfjorden. And a 19-year survey3 of the stomach contents of black-legged kittiwakes (Rissa tridactyla) in the fjord — a type of seabird in the gull family — suggests that, since around 2006, they have started to feast on a wide array of Atlantic fish that seem to have relocated, including Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus), capelin (Mallotus villosus) and Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua).

The presence of these southern migrants seems to support the hypothesis that the Arctic will become more and more similar to the North Atlantic Ocean, a process aptly called Atlantification.

Arctic adapters

Some newcomers to Kongsfjorden present a challenge for researchers. Luisa Düsedau, a molecular biologist at the Alfred Wegner Institute in Bremerhaven, Germany, says that she and her colleagues now need to keep a watch out for polar bears (Ursus maritimus) as they walk the shoreline to collect specimens such as algae and kelp.

Polar bears now come into the fjord to eat the eggs of eiders along the shoreline.Credit: Geir Wing Gabrielsen

Once upon a time, these massive marine mammals would rarely come into the fjord. But with there being less and less sea ice — which polar bears rely on to hunt — the animals have started shifting tactics. Last summer, according to Gabrielsen, an unprecedented 20 polar bears and cubs travelled to the fjord to eat the eggs of common eiders (Somateria mollissima) and barnacle geese (Branta leucopsis) nesting along the shore.

Polar bears aren’t the only new thing on the shoreline. Scientists used to have a hard time studying anything growing along the tide line because of the sea ice covering it for a large chunk of the year. They also assumed that the ice would prevent most plants from growing there, because it would scrape away anything that tried to take root. Today, thick strands of kelp and algae — some species entirely new to science, according to Düsedau — are flourishing.

Molecular biologist Luisa Düsedau works along the tide line of Kongsfjorden, where you can now see kelp and algae, in 2021.Credit: Nele Schimpf

“It’s like a tiny forest” that forms a home for crabs, worms, snails and many other creatures that used to live on the sea floor, says Düsedau. “It’s blooming.”

The growth is a reminder that nature can adapt, she says. But she also emphasizes that it used to be difficult to know what was actually under the sea ice, especially during the harsh conditions of winter.

With the shifting environment, that is changing. Researchers are trying to establish a baseline for what typically lives in the fjord so that they can systematically bear witness as the ecosystem continues to evolve.

Two years ago, for instance, polar ecologist Charlotte Havermans, also at the Alfred Wegner Institute, travelled with a team to Kongsfjorden to learn whether jellyfish stayed active during the polar winter. The researchers didn’t know whether they would succeed. But upon shining their headlamps into the dark, now-uncovered water, “we saw so many jellyfish”, she says, “it was incredible”. She adds: “There were so many more species in the winter than we thought.” Not only that, but the team found jellyfish DNA in the stomachs of amphipods — tiny crustaceans — also spending the winter in the fjord. It was the first time scientists had spotted Arctic amphipods naturally feeding on jellyfish, and suggested that the jellies play a much bigger part in the winter food chain that previously thought4.

Polar ecologist Charlotte Havermans (centre) and team sample amphipods in the water of Kongsfjorden during winter 2022.Credit: Alfred-Wegener-Institut/Esther Horvath

Kongsfjorden is powerful because it serves as a visual reminder of the power that climate change has to reshape the world, says Gabrielsen. Some 40 years ago, “I was so fascinated” by the fjord’s beauty, he says. Now, “I have grandchildren, and I wonder if they will be able to see what I have seen”.

[ad_2]

Source Article Link

April 6, 1939: John Sculley is born in New York City. He will grow up to be hailed as a business and marketing genius, eventually overseeing Apple’s transformation into the most profitable personal computer company in the world.

April 6, 1939: John Sculley is born in New York City. He will grow up to be hailed as a business and marketing genius, eventually overseeing Apple’s transformation into the most profitable personal computer company in the world.