[ad_1]

Later this week, China will embark on the world’s second-only trip to the Moon’s far side. The goal is to collect the first rocks from inside the South Pole-Aitken (SPA) basin, the largest and oldest impact crater on the lunar surface, and bring them back to Earth for analysis.

A stack of four spacecraft needed to complete this unprecedented and highly challenging mission, known as Chang’e-6, is now tucked into the nose of a 57-metre-tall Long March 5 rocket, waiting to lift off from the Wenchang Satellite Launch Centre on southern China’s Hainan Island.

“The whole process is very complex and risky,” says Jonathan McDowell, an astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

But he says it’s a risk worth taking: “Samples from the SPA basin would be very interesting scientifically and tell us a lot about the history of the Moon and of the early Solar System.”

Far side science

Because the Moon is tidally locked to Earth, humans were only able to see its near side for thousands of years. In 1959, the first lunar far-side images returned by the Soviet probe Luna 3 revealed a face pocked with mountains and impact craters, in contrast to the relatively smooth near side. Scientists have since been collecting data from satellites orbiting the Moon to understand its little-known other half. In 2019, China’s Chang’e-4 became the first spacecraft to soft land and conduct surveys on the Moon’s far side.

The upcoming Chang’e-6 mission, with its landing site carefully chosen by Chinese scientists and international colleagues, aims to give the first accurate measurements of the age and composition of the geology of the Moon’s far side. It might provide key clues to why the two sides of the Moon are so different — the so-called lunar dichotomy mystery — and help test theories about the early history of the Solar System.

The SPA Basin is a vast indentation on the lower half of the far side some 2,500 kilometres wide and 8 kilometres deep. Inside the northeastern part, Li’s team has identified three potential landing areas. They believe the sites could have a variety of materials formed during repeated asteroid impacts and volcanic eruptions over two billion years, and therefore could be scientifically rich.

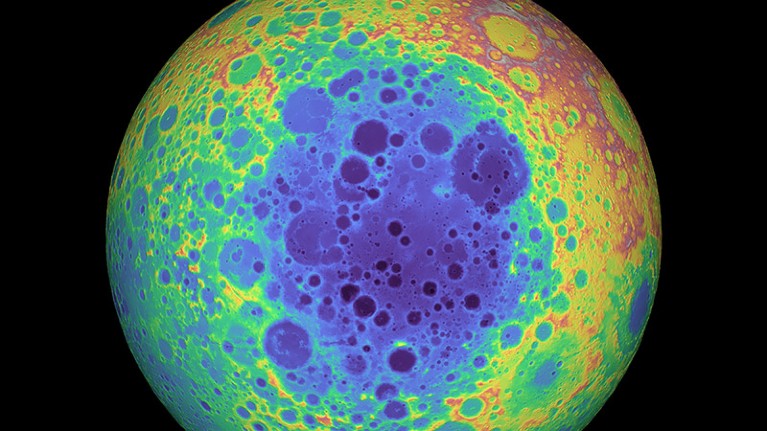

The South Pole-Aitken Basin is the blue area in the centre of this false-colour image. The indentation is 2,500 kilometres wide.Credit: NASA/GSFC/University Of Arizona

The most likely rock to be collected is basalt — dark-coloured cooled lava — which has previously been brought back to Earth for analysis from the Moon’s near side. With the first far-side basalt samples, scientists will be able to date them and assess their chemical composition, giving clues to their formation. “Then we can make comparative studies to understand why volcanic activities happened on a much smaller scale and ended much earlier on the far side of the Moon,” says Long Xiao, a planetary scientist at the China University of Geosciences in Wuhan.

Being able to pin down the SPA Basin’s age would also be a major achievement, says planetary geologist Carolyn van der Bogert from the University of Münster, Germany. It will help settle the long-standing debate about whether the Moon and the inner Solar System was battered by a massive cluster of asteroids between 4.0 and 3.8 billion years ago. If the SPA Basin is older, then it would cast doubt on the heavy bombardment theory.

Besides basalts, scientists hope that Chang’e-6 will also pick up fragments of other rocks that have been scattered during impact events. If the Chinese mission strikes ejecta the from the deeper lunar crust or mantle, it will be scientific gold.

Engineering challenges

Chang’e-6 was originally built as a backup for the Chang’e-5 mission, which successfully returned 1.73 kilograms of samples from the Moon’s near side in 2020. Because the two craft are identical, site selection for Chang’e-6’s landing was constrained to similar latitudes as Chang’e-5’s and needed a relatively flat surface, says Chunlai Li, the mission’s deputy chief designer from the National Astronomical Observatories in Beijing.

Like its predecessor, Chang’e-6 does not pre-determine its landing site but will use its instrumentation during the descent process to find the safest and most favourable spot. “The landing of Chang’e-6 would be more challenging than Chang’e-5 simply because the far side landing site is more rugged,” says Xiao.

Chang’e-6, like its twin, consists of an orbiter, a lander, an ascender and a re-entry module. When the spacecraft arrives at the Moon, it will separate into two parts, with the lander and ascender headed for the lunar surface while the orbiter and re-entry module remain in orbit.

If it pulls off the difficult soft landing, the lander will drill and scoop up two kilograms of soil and rocks. The sampling process needs to be completed within 48 hours, after which the ascender is intended to blast off from the lander and return to the lunar orbiter. There it is supposed to dock and transfer the precious samples to the re-entry module for the trip home.

During the sample collection and lunar surface liftoff, the Chang’e-6 lander would be unable to directly communicate with Earth. Every command will need to go through a relay satellite named Queqiao-2. Launched last month and now operating in a highly elliptical orbit around the Moon, Queqiao-2 is more powerful than the Queqiao satellite which served the Chang’e-4 mission. Its 4.2-metre umbrella-shaped antenna has the ability to simultaneously serve up to ten spacecraft working on the Moon’s far side.

International collaboration

Chang’e-6 is also carrying scientific payloads from France, Sweden, Italy and Pakistan. The Detection of Outgassing RadoN (DORN), which will be the first French instrument on the Moon, plans to use radon released from the lunar surface as a tracer to study the origin and dynamics of the Moon’s faint atmosphere. Pierre-Yves Meslin, a planetary scientist at the Research Institute in Astrophysics and Planetology in Toulouse, France, says previous spacecraft have measured radon gas movement from orbit, but surface-level radon information is the missing piece of the puzzle.

The Negative Ions at the Lunar Surface, a payload developed in Sweden with funding from the European Space Agency, will seek to answer the question of why no negative ions have yet been detected on the lunar surface. Negative particles could be short-lived, formed either by atoms at the surface snatching electrons from the solar wind, or by molecules breaking apart from the high-energy solar radiation. The biggest challenge for this instrument is overheating, since it needs to face the Sun, says ESA project manager Neil Melville. But he says one hour of operation should be enough to gather the data.

Italy’s National Institute of Nuclear Physics is sending a laser retroreflector for distance measurements. And Pakistan has piggy-backed its first lunar satellite to the Chang’e 6 orbiter, which will deploy after entering the lunar orbit.

Both surface instruments need to complete their work and send data back to Earth within the 48-hour window. “As soon as the samples lift off, the ascender will bring with it the communications and control system it shares with the lander. Even if the instruments on the lander continue to take data, there is no way to receive them here on Earth,” Li says

He says that like Chang’e-5 samples, the returned Chang’e-6 samples will be shared with the international community.

“When those samples come back to Earth, they will be like a Christmas present — whoever opens it will be happily surprised,” Bogert says.

[ad_2]

Source Article Link