[ad_1]

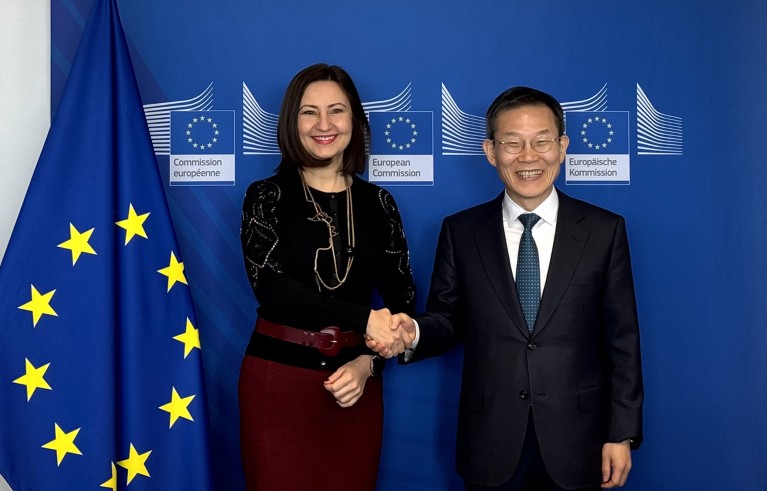

South Korean science minister Lee Jong-ho and European commissioner for research Iliana Ivanova celebrate South Korea joining Horizon Europe in March. Viewing research through a security lens makes it harder for other non-EU countries to follow.Credit: HANDOUT/EPA-EFE/Shutterstock

Last month, the European Commission published a ‘course correction’ for its Horizon Europe research fund, which is worth around US$100 billion over seven years, from 2021 to 2027. It’s not easy to make major alterations at the mid-way point of such a large enterprise, whose two predecessors funded 1.5 million collaborations across 150 countries. But the European Union has made substantial changes in the fund’s latest strategic plan that researchers need to be aware of.

One of the most important is a phrase now peppered throughout the document: open strategic autonomy.

This political concept means that the EU will strengthen its self-sufficiency while remaining open to cooperation with other regions. The term is not new — in Horizon Europe’s first strategic plan (for 2021–24), open strategic autonomy was one of four priority areas for funded projects, alongside the green transition, the digital transition and building a more resilient, competitive, inclusive and democratic Europe.

Horizon Europe turmoil changed the lives of these five scientists

The EU has reduced these four priorities to three — and open strategic autonomy has been upgraded. It is now an overarching theme for all research funded by Horizon Europe from 2025 to the end of 2027. Barring a sudden outbreak of world peace, this mode of thinking and action is expected to influence — if not dominate — the next iteration of Horizon Europe, called FP10, which will start in 2028.

This change of priorities is concerning researchers. The European Research Council (ERC), which funds investigator-led research and is part of Horizon Europe, issued a statement at the end of January, saying: “The ERC’s independence and autonomy must be protected under FP10.”

But for now, just as a tanker cannot be turned around at full speed, Horizon Europe retains key elements of the original plan. The EU wants to maintain its climate funding (35% of the total Horizon Europe budget) and increase biodiversity funding to 10% of the budget, which are both welcome decisions. It is also committed to the idea of moonshot-style missions: specific goal-oriented funds to tackle urgent global challenges, such as improving soil health and establishing carbon-neutral cities. It plans to meaningfully integrate social-sciences and humanities researchers into collaborations — not just include them as afterthoughts — and to improve diversity and equity. And it is continuing to reach beyond its borders.

War shattered Ukrainian science — its rebirth is now taking shape

Last week, it was announced that South Korea’s researchers will be able to participate in EU-funded projects related to global challenges. Last November, Canada also joined the programme. And New Zealand before that. The United Kingdom’s researchers are also back, after a gap of nearly four years after Brexit. These are, broadly speaking, all representative democracies with which EU countries have defence- and security-cooperation agreements. The principle of open strategic autonomy will make it more difficult to cooperate with countries for which this is not the case.

The EU is obviously responding to the world-changing events of the past decade. When discussions about the first iteration of Horizon Europe were beginning, wars, pandemics and the election of populist leaders mostly seemed to be twentieth-century concerns. As the EU — and its international partners, too — responded to levels of instability that few were expecting, heavier emphasis on a research agenda to strengthen supply chains, ensure resilience of essential infrastructure and establish more manufacturing at or closer to home is understandable.

But a security mindset cannot be baked into what is fundamentally an open and autonomous research cooperation fund. In addition to sharing research and cooperating in the development of new technologies, Horizon Europe — originally called the Framework Programme — was created to re-establish trust between Europe’s nations in the second half of the twentieth century. It was part of a larger effort to prevent them from going to war with each other.

Strategic plans have to remain flexible. Circumstances change, and it’s important to be able to make adjustments when that happens. But making open strategic autonomy a theme for all EU funding is neither sensible nor desirable.

[ad_2]

Source Article Link