[ad_1]

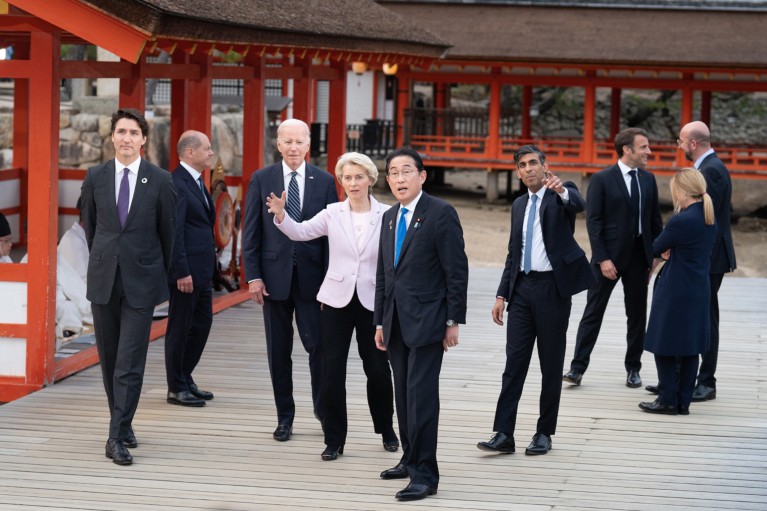

Policymakers often work behind closed doors — but the documents they produce offer clues about the research that influences them.Credit: Stefan Rousseau/Getty

When David Autor co-wrote a paper on how computerization affects job skill demands more than 20 years ago, a journal took 18 months to consider it — only to reject it after review. He went on to submit it to The Quarterly Journal of Economics, which eventually published the work1 in November 2003.

Autor’s paper is now the third most cited in policy documents worldwide, according to an analysis of data provided exclusively to Nature. It has accumulated around 1,100 citations in policy documents, show figures from the London-based firm Overton (see ‘The most-cited papers in policy’), which maintains a database of more than 12 million policy documents, think-tank papers, white papers and guidelines.

“I thought it was destined to be quite an obscure paper,” recalls Autor, a public-policy scholar and economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge. “I’m excited that a lot of people are citing it.”

The top ten most cited papers in policy documents are dominated by economics research. When economics studies are excluded, a 1997 Nature paper2 about Earth’s ecosystem services and natural capital is second on the list, with more than 900 policy citations. The paper has also garnered more than 32,000 references from other studies, according to Google Scholar. Other highly cited non-economics studies include works on planetary boundaries, sustainable foods and the future of employment (see ‘Most-cited papers — excluding economics research’).

These lists provide insight into the types of research that politicians pay attention to, but policy citations don’t necessarily imply impact or influence, and Overton’s database has a bias towards documents published in English.

Interdisciplinary impact

Overton usually charges a licence fee to access its citation data. But last year, the firm worked with the London-based publisher Sage to release a free web-based tool that allows any researcher to find out how many times policy documents have cited their papers or mention their names. Overton and Sage said they created the tool, called Sage Policy Profiles, to help researchers to demonstrate the impact or influence their work might be having on policy. This can be useful for researchers during promotion or tenure interviews and in grant applications.

Autor thinks his study stands out because his paper was different from what other economists were writing at the time. It suggested that ‘middle-skill’ work, typically done in offices or factories by people who haven’t attended university, was going to be largely automated, leaving workers with either highly skilled jobs or manual work. “It has stood the test of time,” he says, “and it got people to focus on what I think is the right problem.” That topic is just as relevant today, Autor says, especially with the rise of artificial intelligence.

Walter Willett, an epidemiologist and food scientist at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, Massachusetts, thinks that interdisciplinary teams are most likely to gain a lot of policy citations. He co-authored a paper on the list of most cited non-economics studies: a 2019 work3 that was part of a Lancet commission to investigate how to feed the global population a healthy and environmentally sustainable diet by 2050 and has accumulated more than 600 policy citations.

“I think it had an impact because it was clearly a multidisciplinary effort,” says Willett. The work was co-authored by 37 scientists from 17 countries. The team included researchers from disciplines including food science, health metrics, climate change, ecology and evolution and bioethics. “None of us could have done this on our own. It really did require working with people outside our fields.”

Sverker Sörlin, an environmental historian at the KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, agrees that papers with a diverse set of authors often attract more policy citations. “It’s the combined effect that is often the key to getting more influence,” he says.

Has your research influenced policy? Use this free tool to check

Sörlin co-authored two papers in the list of top ten non-economics papers. One of those is a 2015 Science paper4 on planetary boundaries — a concept defining the environmental limits in which humanity can develop and thrive — which has attracted more than 750 policy citations. Sörlin thinks one reason it has been popular is that it’s a sequel to a 2009 Nature paper5 he co-authored on the same topic, which has been cited by policy documents 575 times.

Although policy citations don’t necessarily imply influence, Willett has seen evidence that his paper is prompting changes in policy. He points to Denmark as an example, noting that the nation is reformatting its dietary guidelines in line with the study’s recommendations. “I certainly can’t say that this document is the only thing that’s changing their guidelines,” he says. But “this gave it the support and credibility that allowed them to go forward”.

Broad brush

Peter Gluckman, who was the chief science adviser to the prime minister of New Zealand between 2009 and 2018, is not surprised by the lists. He expects policymakers to refer to broad-brush papers rather than those reporting on incremental advances in a field.

Gluckman, a paediatrician and biomedical scientist at the University of Auckland in New Zealand, notes that it’s important to consider the context in which papers are being cited, because studies reporting controversial findings sometimes attract many citations. He also warns that the list is probably not comprehensive: many policy papers are not easily accessible to tools such as Overton, which uses text mining to compile data, and so will not be included in the database.

The top 100 papers

“The thing that worries me most is the age of the papers that are involved,” Gluckman says. “Does that tell us something about just the way the analysis is done or that relatively few papers get heavily used in policymaking?”

Gluckman says it’s strange that some recent work on climate change, food security, social cohesion and similar areas hasn’t made it to the non-economics list. “Maybe it’s just because they’re not being referred to,” he says, or perhaps that work is cited, in turn, in the broad-scope papers that are most heavily referenced in policy documents.

As for Sage Policy Profiles, Gluckman says it’s always useful to get an idea of which studies are attracting attention from policymakers, but he notes that studies often take years to influence policy. “Yet the average academic is trying to make a claim here and now that their current work is having an impact,” he adds. “So there’s a disconnect there.”

Willett thinks policy citations are probably more important than scholarly citations in other papers. “In the end, we don’t want this to just sit on an academic shelf.”

[ad_2]

Source Article Link