[ad_1]

Hello Nature readers, would you like to get this Briefing in your inbox free every day? Sign up here.

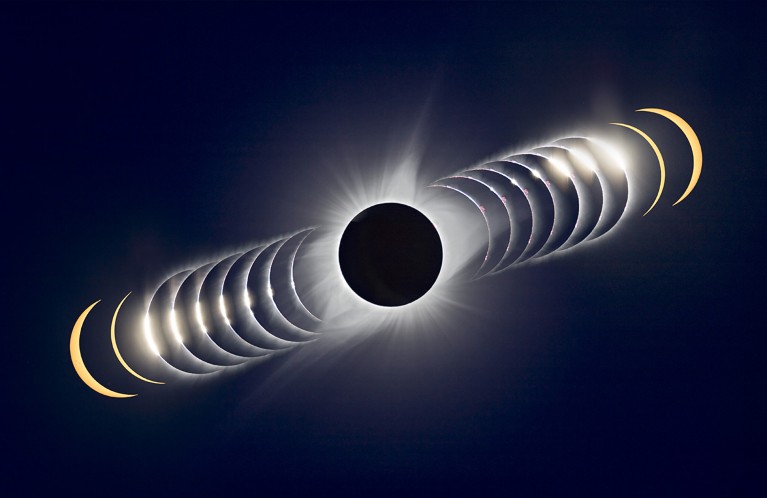

Viewers along the eclipse’s path in North America will watch the Moon cross the Sun’s face and block the solar disk, offering the chance to see its outer atmosphere by eye.Credit: Alan Dyer/VW Pics/UIG via Getty

On 8 April, researchers will get an unprecedented view of the Sun’s outer wispy atmosphere: the corona. The solar eclipse visible in parts of North America will coincide with a solar maximum — a period of extreme activity that occurs every 11 years. One research team will chase the eclipse from a jet, adding 90 more seconds of observation time to the maximum of 4 minutes and 30 seconds seen by observers on the ground. One question they’re hoping to answer: why the corona is so much hotter than the solar surface. That, says solar physicist James Klimchuk, is like walking away from a campfire — but finding that instead of cooling down, you get warmer.

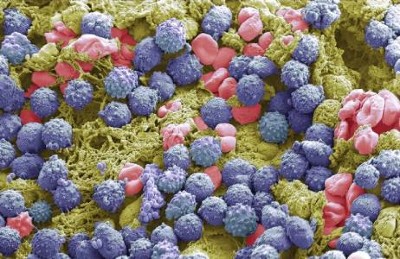

A diabetes drug called lixisenatide has shown promise in slowing the progression of Parkinson’s disease. Lixisenatide is in the family of GLP-1 receptor agonists, such as Ozempic, that have made headlines as weight-loss drugs. In the latest clinical trial, lixisenatide was given to people with mild to moderate Parkinson’s who were already receiving a standard treatment for the condition. After a year they saw no worsening of their symptoms, unlike a control group whose condition did worsen. Further work is needed to reduce the drug’s side effects, such as nausea and vomiting, and to determine whether its benefits last. “We’re all cautious. There’s a long history of trying different things in Parkinson’s that ultimately didn’t work,” says neurologist David Standaert.

Reference: The New England Journal of Medicine paper

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, one of the world’s top biomedical research funders, will from next year require grant holders to make their research publicly available as preprints, which are not peer reviewed. It will also no longer pay article-processing charges (APCs) to publishers in order to secure open access, in which the peer-reviewed version of the paper is free to read. The change follows criticism that APCs create inequities because of the costs they push onto researchers and funders. “We’ve become convinced that this money could be better spent elsewhere,” said a Gates representative.

Features & opinion

This week marks 30 years since the start of the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, in which members of the Hutu ethnic group killed an estimated 800,000 people from Tutsi communities. The event is now one of the most researched of its kind. These studies are difficult, not least because because the genocide almost wiped out Rwanda’s academic community. But efforts, especially by local researchers, are helping to inform responses to other violent crises and longer-term approaches to healing. Sociologist Assumpta Mugiraneza is leading challenging work that gathers testimonies from the genocide — and of the rich lives people had before the atrocity. To think about genocide, she says, “we must dare to seek humanity where humanity has been denied”.

Two future academics — a rat and a raven — ponder the fate of past primates in the latest short story for Nature’s Futures series.

Andrew Robinson’s pick of the top five science books to read this week includes an account of women working in nature and a thoughtful history of how our unequal society deals with epidemics.

When Brazilian biologist Fernanda Staniscuaski returned from parental leave, her grant applications started to be rejected because she “was not producing as much as my peers”. “Maybe I was never meant to be in science,” she recalls thinking. As the founder of the Parent in Science movement, she is now lobbying for greater acceptance of career breaks. As a first step, the Brazilian Ministry of Education has created a working group to develop a national policy for mothers in academia. “That was huge,” Staniscuaski says.

In our penguin-puzzle this week, Leif Penguinson is exploring a rock formation on the Barker Dam Trail in Joshua Tree National Park, California. Can you find the penguin?

The answer will be in Monday’s e-mail, all thanks to Briefing photo editor and penguin wrangler Tom Houghton.

This newsletter is always evolving — tell us what you think! Please send your feedback to [email protected].

Flora Graham, senior editor, Nature Briefing

With contributions by Katrina Krämer, Sarah Tomlin and Sara Phillips

Want more? Sign up to our other free Nature Briefing newsletters:

• Nature Briefing: Anthropocene — climate change, biodiversity, sustainability and geoengineering

• Nature Briefing: AI & Robotics — 100% written by humans, of course

• Nature Briefing: Cancer — a weekly newsletter written with cancer researchers in mind

• Nature Briefing: Translational Research covers biotechnology, drug discovery and pharma

[ad_2]

Source Article Link