[ad_1]

Quantum mechanics is an extraordinarily successful scientific theory, on which much of our technology-obsessed lifestyles depend. It is also bewildering. Although the theory works, it leaves physicists chasing probabilities instead of certainties and breaks the link between cause and effect. It gives us particles that are waves and waves that are particles, cats that seem to be both alive and dead, and lots of spooky quantum weirdness around hard-to-explain phenomena, such as quantum entanglement.

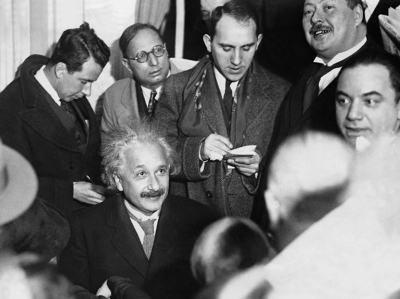

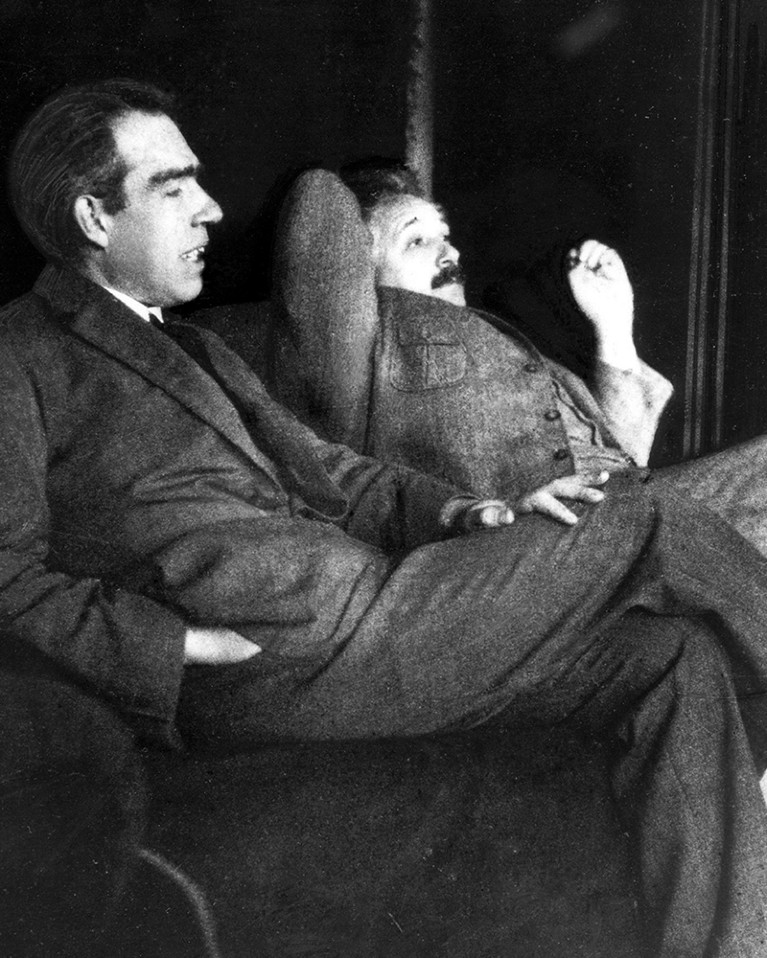

Myths are also rife. For instance, in the early twentieth century, when the theory’s founders were arguing among themselves about what it all meant, the views of Danish physicist Niels Bohr came to dominate. Albert Einstein famously disagreed with him and, in the 1920s and 1930s, the two locked horns in debate. A persistent myth was created that suggests Bohr won the argument by browbeating the stubborn and increasingly isolated Einstein into submission. Acting like some fanatical priesthood, physicists of Bohr’s ‘church’ sought to shut down further debate. They established the ‘Copenhagen interpretation’, named after the location of Bohr’s institute, as a dogmatic orthodoxy.

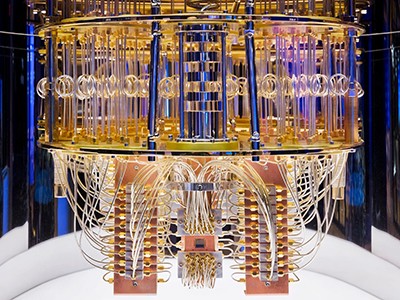

My latest book Quantum Drama, co-written with science historian John Heilbron, explores the origins of this myth and its role in motivating the singular personalities that would go on to challenge it. Their persistence in the face of widespread indifference paid off, because they helped to lay the foundations for a quantum-computing industry expected to be worth tens of billions by 2040.

John died on 5 November 2023, so sadly did not see his last work through to publication. This essay is dedicated to his memory.

Foundational myth

A scientific myth is not produced by accident or error. It requires effort. “To qualify as a myth, a false claim should be persistent and widespread,” Heilbron said in a 2014 conference talk. “It should have a plausible and assignable reason for its endurance, and immediate cultural relevance,” he noted. “Although erroneous or fabulous, such myths are not entirely wrong, and their exaggerations bring out aspects of a situation, relationship or project that might otherwise be ignored.”

Does quantum theory imply the entire Universe is preordained?

To see how these observations apply to the historical development of quantum mechanics, let’s look more closely at the Bohr–Einstein debate. The only way to make sense of the theory, Bohr argued in 1927, was to accept his principle of complementarity. Physicists have no choice but to describe quantum experiments and their results using wholly incompatible, yet complementary, concepts borrowed from classical physics.

In one kind of experiment, an electron, for example, behaves like a classical wave. In another, it behaves like a classical particle. Physicists can observe only one type of behaviour at a time, because there is no experiment that can be devised that could show both behaviours at once.

Bohr insisted that there is no contradiction in complementarity, because the use of these classical concepts is purely symbolic. This was not about whether electrons are really waves or particles. It was about accepting that physicists can never know what an electron really is and that they must reach for symbolic descriptions of waves and particles as appropriate. With these restrictions, Bohr regarded the theory to be complete — no further elaboration was necessary.

Such a pronouncement prompts an important question. What is the purpose of physics? Is its main goal to gain ever-more-detailed descriptions and control of phenomena, regardless of whether physicists can understand these descriptions? Or, rather, is it a continuing search for deeper and deeper insights into the nature of physical reality?

Einstein preferred the second answer, and refused to accept that complementarity could be the last word on the subject. In his debate with Bohr, he devised a series of elaborate thought experiments, in which he sought to demonstrate the theory’s inconsistencies and ambiguities, and its incompleteness. These were intended to highlight matters of principle; they were not meant to be taken literally.

Entangled probabilities

In 1935, Einstein’s criticisms found their focus in a paper1 published with his colleagues Boris Podolsky and Nathan Rosen at the Institute for Advanced Studies in Princeton, New Jersey. In their thought experiment (known as EPR, the authors’ initials), a pair of particles (A and B) interact and move apart. Suppose each particle can possess, with equal probability, one of two quantum properties, which for simplicity I will call ‘up’ and ‘down’, measured in relation to some instrument setting. Assuming their properties are correlated by a physical law, if A is measured to be ‘up’, B must be ‘down’, and vice versa. The Austrian physicist Erwin Schrödinger invented the term entangled to describe this kind of situation.

How Einstein built on the past to make his breakthroughs

If the entangled particles are allowed to move so far apart that they can no longer affect one another, physicists might say that they are no longer in ‘causal contact’. Quantum mechanics predicts that scientists should still be able to measure A and thereby — with certainty — infer the correlated property of B.

But the theory gives us only probabilities. We have no way of knowing in advance what result we will get for A. If A is found to be ‘down’, how does the distant, causally disconnected B ‘know’ how to correlate with its entangled partner and give the result ‘up’? The particles cannot break the correlation, because this would break the physical law that created it.

Physicists could simply assume that, when far enough apart, the particles are separate and distinct, or ‘locally real’, each possessing properties that were fixed at the moment of their interaction. Suppose A sets off towards a measuring instrument carrying the property ‘up’. A devious experimenter is perfectly at liberty to change the instrument setting so that when A arrives, it is now measured to be ‘down’. How, then, is the correlation established? Do the particles somehow remain in contact, sending messages to each other or exerting influences on each other over vast distances at speeds faster than light, in conflict with Einstein’s special theory of relativity?

The alternative possibility, equally discomforting to contemplate, is that the entangled particles do not actually exist independently of each other. They are ‘non-local’, implying that their properties are not fixed until a measurement is made on one of them.

Both these alternatives were unacceptable to Einstein, leading him to conclude that quantum mechanics cannot be complete.

Niels Bohr (left) and Albert Einstein.Credit: Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty

The EPR thought experiment delivered a shock to Bohr’s camp, but it was quickly (if unconvincingly) rebuffed by Bohr. Einstein’s challenge was not enough; he was content to criticize the theory but there was no consensus on an alternative to Bohr’s complementarity. Bohr was judged by the wider scientific community to have won the debate and, by the early 1950s, Einstein’s star was waning.

Unlike Bohr, Einstein had established no school of his own. He had rather retreated into his own mind, in vain pursuit of a theory that would unify electromagnetism and gravity, and so eliminate the need for quantum mechanics altogether. He referred to himself as a “lone traveler”. In 1948, US theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer remarked to a reporter at Time magazine that the older Einstein had become “a landmark, but not a beacon”.

Prevailing view

Subsequent readings of this period in quantum history promoted a persistent and widespread suggestion that the Copenhagen interpretation had been established as the orthodox view. I offer two anecdotes as illustration. When learning quantum mechanics as a graduate student at Harvard University in the 1950s, US physicist N. David Mermin recalled vivid memories of the responses that his conceptual enquiries elicited from his professors, whom he viewed as ‘agents of Copenhagen’. “You’ll never get a PhD if you allow yourself to be distracted by such frivolities,” they advised him, “so get back to serious business and produce some results. Shut up, in other words, and calculate.”

The spy who flunked it: Kurt Gödel’s forgotten part in the atom-bomb story

It seemed that dissidents faced serious repercussions. When US physicist John Clauser — a pioneer of experimental tests of quantum mechanics in the early 1970s — struggled to find an academic position, he was clear in his own mind about the reasons. He thought he had fallen foul of the ‘religion’ fostered by Bohr and the Copenhagen church: “Any physicist who openly criticized or even seriously questioned these foundations … was immediately branded as a ‘quack’. Quacks naturally found it difficult to find decent jobs within the profession.”

But pulling on the historical threads suggests a different explanation for both Mermin’s and Clauser’s struggles. Because there was no viable alternative to complementarity, those writing the first post-war student textbooks on quantum mechanics in the late 1940s had little choice but to present (often garbled) versions of Bohr’s theory. Bohr was notoriously vague and more than occasionally incomprehensible. Awkward questions about the theory’s foundations were typically given short shrift. It was more important for students to learn how to apply the theory than to fret about what it meant.

One important exception is US physicist David Bohm’s 1951 book Quantum Theory, which contains an extensive discussion of the theory’s interpretation, including EPR’s challenge. But, at the time, Bohm stuck to Bohr’s mantra.

The Americanization of post-war physics meant that no value was placed on ‘philosophical’ debates that did not yield practical results. The task of ‘getting to the numbers’ meant that there was no time or inclination for the kind of pointless discussion in which Bohr and Einstein had indulged. Pragmatism prevailed. Physicists encouraged their students to choose research topics that were likely to provide them with a suitable grounding for an academic career, or ones that appealed to prospective employers. These did not include research on quantum foundations.

These developments conspired to produce a subtly different kind of orthodoxy. In The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962), US philosopher Thomas Kuhn describes ‘normal’ science as the everyday puzzle-solving activities of scientists in the context of a prevailing ‘paradigm’. This can be interpreted as the foundational framework on which scientific understanding is based. Kuhn argued that researchers pursuing normal science tend to accept foundational theories without question and seek to solve problems within the bounds of these concepts. Only when intractable problems accumulate and the situation becomes intolerable might the paradigm ‘shift’, in a process that Kuhn likened to a political revolution.

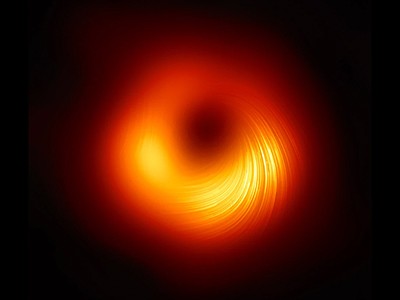

Do black holes explode? The 50-year-old puzzle that challenges quantum physics

The prevailing view also defines what kinds of problem the community will accept as scientific and which problems researchers are encouraged (and funded) to investigate. As Kuhn acknowledged in his book: “Other problems, including many that had previously been standard, are rejected as metaphysical, as the concern of another discipline, or sometimes as just too problematic to be worth the time.”

What Kuhn says about normal science can be applied to ‘mainstream’ physics. By the 1950s, the physics community had become broadly indifferent to foundational questions that lay outside the mainstream. Such questions were judged to belong in a philosophy class, and there was no place for philosophy in physics. Mermin’s professors were not, as he had first thought, ‘agents of Copenhagen’. As he later told me, his professors “had no interest in understanding Bohr, and thought that Einstein’s distaste for [quantum mechanics] was just silly”. Instead, they were “just indifferent to philosophy. Full stop. Quantum mechanics worked. Why worry about what it meant?”

It is more likely that Clauser fell foul of the orthodoxy of mainstream physics. His experimental tests of quantum mechanics2 in 1972 were met with indifference or, more actively, dismissal as junk or fringe science. After all, as expected, quantum mechanics passed Clauser’s tests and arguably nothing new was discovered. Clauser failed to get an academic position not because he had had the audacity to challenge the Copenhagen interpretation; his audacity was in challenging the mainstream. As a colleague told Clauser later, physics faculty members at one university to which he had applied “thought that the whole field was controversial”.

Aspect, Clauser and Zeilinger won the 2022 physics Nobel for work on entangled photons.Credit: Claudio Bresciani/TT News Agency/AFP via Getty

However, it’s important to acknowledge that the enduring myth of the Copenhagen interpretation contains grains of truth, too. Bohr had a strong and domineering personality. He wanted to be associated with quantum theory in much the same way that Einstein is associated with theories of relativity. Complementarity was accepted as the last word on the subject by the physicists of Bohr’s school. Most vociferous were Bohr’s ‘bulldog’ Léon Rosenfeld, Wolfgang Pauli and Werner Heisenberg, although all came to hold distinct views about what the interpretation actually meant.

They did seek to shut down rivals. French physicist Louis de Broglie’s ‘pilot wave’ interpretation, which restores causality and determinism in a theory in which real particles are guided by a real wave, was shot down by Pauli in 1927. Some 30 years later, US physicist Hugh Everett’s relative state or many-worlds interpretation was dismissed, as Rosenfeld later described, as “hopelessly wrong ideas”. Rosenfeld added that Everett “was undescribably stupid and could not understand the simplest things in quantum mechanics”.

Unorthodox interpretations

But the myth of the Copenhagen interpretation served an important purpose. It motivated a project that might otherwise have been ignored. Einstein liked Bohm’s Quantum Theory and asked to see him in Princeton in the spring of 1951. Their discussion prompted Bohm to abandon Bohr’s views, and he went on to reinvent de Broglie’s pilot wave theory. He also developed an alternative to the EPR challenge that held the promise of translation into a real experiment.

Befuddled by Bohrian vagueness, finding no solace in student textbooks and inspired by Bohm, Irish physicist John Bell pushed back against the Copenhagen interpretation and, in 1964, built on Bohm’s version of EPR to develop a now-famous theorem3. The assumption that the entangled particles A and B are locally real leads to predictions that are incompatible with those of quantum mechanics. This was no longer a matter for philosophers alone: this was about real physics.

It took Clauser three attempts to pass his graduate course on advanced quantum mechanics at Columbia University because his brain “kind of refused to do it”. He blamed Bohr and Copenhagen, found Bohm and Bell, and in 1972 became the first to perform experimental tests of Bell’s theorem with entangled photons2.

How to introduce quantum computers without slowing economic growth

French physicist Alain Aspect similarly struggled to discern a “physical world behind the mathematics”, was perplexed by complementarity (“Bohr is impossible to understand”) and found Bell. In 1982, he performed what would become an iconic test of Bell’s theorem4, changing the settings of the instruments used to measure the properties of pairs of entangled photons while the particles were mid-flight. This prevented the photons from somehow conspiring to correlate themselves through messages or influences passed between them, because the nature of the measurements to be made on them was not set until they were already too far apart. All these tests settled in favour of quantum mechanics and non-locality.

Although the wider physics community still considered testing quantum mechanics to be a fringe science and mostly a waste of time, exposing a hitherto unsuspected phenomenon — quantum entanglement and non-locality — was not. Aspect’s cause was aided by US physicist Richard Feynman, who in 1981 had published his own version of Bell’s theorem5 and had speculated on the possibility of building a quantum computer. In 1984, Charles Bennett at IBM and Giles Brassard at the University of Montreal in Canada proposed entanglement as the basis for an innovative system of quantum cryptography6.

It is tempting to think that these developments finally helped to bring work on quantum foundations into mainstream physics, making it respectable. Not so. According to Austrian physicist Anton Zeilinger, who has helped to found the science of quantum information and its promise of a quantum technology, even those working in quantum information consider foundations to be “not the right thing”. “We don’t understand the reason why. Must be psychological reasons, something like that, something very deep,” Zeilinger says. The lack of any kind of physical mechanism to explain how entanglement works does not prevent the pragmatic physicist from getting to the numbers.

Similarly, by awarding the 2022 Nobel Prize in Physics to Clauser, Aspect and Zeilinger, the Nobels as an institution have not necessarily become friendly to foundational research. Commenting on the award, the chair of the Nobel Committee for Physics, Anders Irbäck, said: “It has become increasingly clear that a new kind of quantum technology is emerging. We can see that the laureates’ work with entangled states is of great importance, even beyond the fundamental questions about the interpretation of quantum mechanics.” Or, rather, their work is of great importance because of the efforts of those few dissidents, such as Bohm and Bell, who were prepared to resist the orthodoxy of mainstream physics, which they interpreted as the enduring myth of the Copenhagen interpretation.

The lesson from Bohr–Einstein and the riddle of entanglement is this. Even if we are prepared to acknowledge the myth, we still need to exercise care. Heilbron warned against wanton slaying: “The myth you slay today may contain a truth you need tomorrow.”

[ad_2]

Source Article Link