[ad_1]

Kidney disease is growing worldwide. The secretariat of the World Health Organization has welcomed the call to include it as a non-communicable disease that causes premature deaths.Credit: Vsevolod Zviryk/SPL

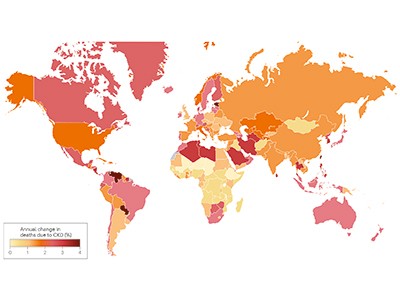

A quiet epidemic is building around the world. It is the third-fastest-growing cause of death globally. By 2040, it is expected to become the fifth-highest cause of years of life lost. Already, 850 million people are affected, and treating them is draining public-health coffers: the US government-funded health-care plan Medicare alone spends US$130 billion to do so each year. The culprit is kidney disease, a condition in which damage to the kidneys prevents them from filtering the blood.

And yet, in discussions of priorities for global public health, the words ‘kidney disease’ do not always feature. One reason for this is that kidney disease is not on the World Health Organization (WHO) list of priority non-communicable diseases (NCDs) that cause premature deaths. The roster of such NCDs includes heart disease, stroke, diabetes, cancer and chronic lung disease. With kidney disease missing, awareness of its growing impact remains low.

Chronic kidney disease and the global public health agenda: an international consensus

The authors of an article in Nature Reviews Nephrology this week want to change that (A. Francis et al. Nature Rev. Nephrol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-024-00820-6; 2024). They are led by the three largest professional organizations working in kidney health — the International Society of Nephrology, the American Society of Nephrology and the European Renal Association — and they’re urging the WHO to include kidney disease on the priority NCD list.

This will, the authors argue, bring attention to the growing threat, which is particularly dire for people in low- and lower-middle-income countries, who already bear two‑thirds of the world’s kidney-disease burden. Adding kidney disease to the list will also mean that reducing deaths from it could become more of a priority for the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals target to reduce premature deaths from NCDs by one-third by 2030.

As of now, rates of chronic kidney disease are likely to increase in low- and lower-middle-income countries as the proportion of older people in their populations increases. Inclusion on the WHO list could provide an incentive for health authorities to prioritize treatments, data collection and other research, along with funding, as with other NCDs.

Kidney disease often accompanies other conditions that do appear on the NCD list, such as heart disease, cancer and diabetes — indeed, kidney-disease deaths caused specifically by diabetes are on the list. But the article authors argue that “tackling diabetes and heart disease alone will not target the core drivers of a large proportion of kidney diseases”. Both acute and chronic kidney disease can have many causes. They can be caused by infection or exposure to toxic substances. Increasingly, the consequences of global climate change, including high temperatures and reduced availability of fresh water, are thought to be contributing to the global burden of kidney disease, as well.

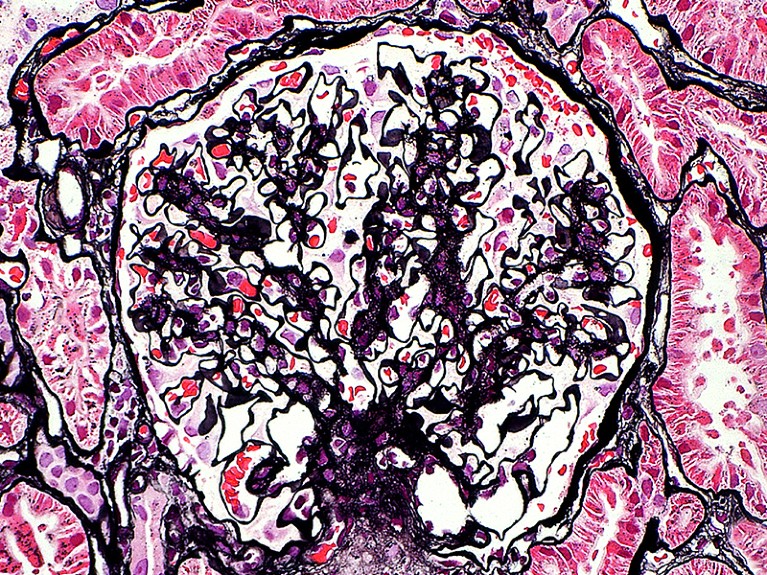

The kidney glomerulus filters waste products from the blood. In people with damaged kidneys, this happens through dialysis.Credit: Ziad M. El-Zaatari/SPL

The WHO secretariat, which works closely with the nephrology community, welcomes the call to include kidney disease as an NCD that causes premature deaths, says Slim Slama, who heads the NCD unit at the secretariat in Geneva, Switzerland. The data support including kidney disease as an NCD driver of premature death, he adds.

The decision to include kidney disease along with other priority NCDs isn’t only down to the WHO, however. There must be conversations between the secretariat, WHO member states, the nephrology community, patient advocates and others. WHO member states need to instruct the agency to take the steps to make it happen, including providing appropriate funding for strategic and technical assistance.

Data and funding gaps

Three reports based on surveys by the International Society of Nephrology since 2016 highlight the scale of data gaps (A. K. Bello et al. Lancet Glob. Health 12, E382–E395; 2024). In many countries, screening for kidney disease is difficult to access and a large proportion of cases go undetected and therefore uncounted. For example, it is not known precisely how many people with kidney failure die each year because of lack of access to dialysis or transplantation: the numbers are somewhere between two million and seven million, according to the WHO. Advocates must push public-health officials in more countries to collect the data needed to monitor kidney disease and the impact of prevention and treatment efforts.

Even with better data, treatments for kidney disease are often prohibitively expensive. They include dialysis, an intervention to filter the blood when kidneys cannot. Dialysis is often required two or three times weekly for the remainder of the recipient’s life, or until they can receive a transplant, and it is notoriously costly. In Thailand, for example, it accounted for 3% of the country’s total health-care expenditures in 2022, according to the country’s parliamentary budget office.

End chronic kidney disease neglect

These costs could come down if people who have diabetes or high blood pressure, for example, could be routinely screened for impaired kidney function, because they are at high risk of developing chronic kidney disease. This would enable kidney damage to be detected early, before symptoms set in, opening the way for treatments that do not immediately require dialysis or transplant surgery.

New drugs that boost weight loss and treat type 2 diabetes could also help to prevent or reduce stress on the kidneys, but these, too, are too expensive for many people in need. That is why something needs to be done to make drugs more affordable. The pharmaceutical industry, which has become extremely profitable, has a crucial role. In Denmark, for example, the industry’s profits helped to tip the national economy from recession into growth in 2023, according to the public agency Statistics Denmark. The COVID-19 pandemic showed that making profits and making drugs available, and affordable, to a wide population need not be mutually exclusive. Similarly innovative thinking is now needed. “The whole world needs to reckon with this kidney problem,” says Valerie Luyckx, a biomedical ethicist at the University of Zurich in Switzerland.

The WHO adding kidney disease to its priority list could also attract funding for treatment, research and disease registries. That could jump-start the development of new treatments and help to make current treatments more affordable and accessible.

NCDs are responsible for 74% of deaths worldwide, but the world’s biggest donors to global health currently devote less than 2% of their budgets for international health assistance to NCD prevention and control, and not including kidney disease. Drawing more attention to the quiet rampage of kidney disease among some of the most vulnerable people would be one important step in turning these statistics around.

[ad_2]

Source Article Link