[ad_1]

Climate scientist Tapio Schneider is delighted that machine learning has taken the drudgery out of his day. When he first started modelling how clouds form, more than a decade ago, this mostly involved painstakingly tweaking equations that describe how water droplets, air flow and temperature interact. But since 2017, machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI) have transformed the way he works.

“Machine learning makes this science a lot more fun,” says Schneider, who works at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. “It’s vastly faster, more satisfying and you can get better solutions.”

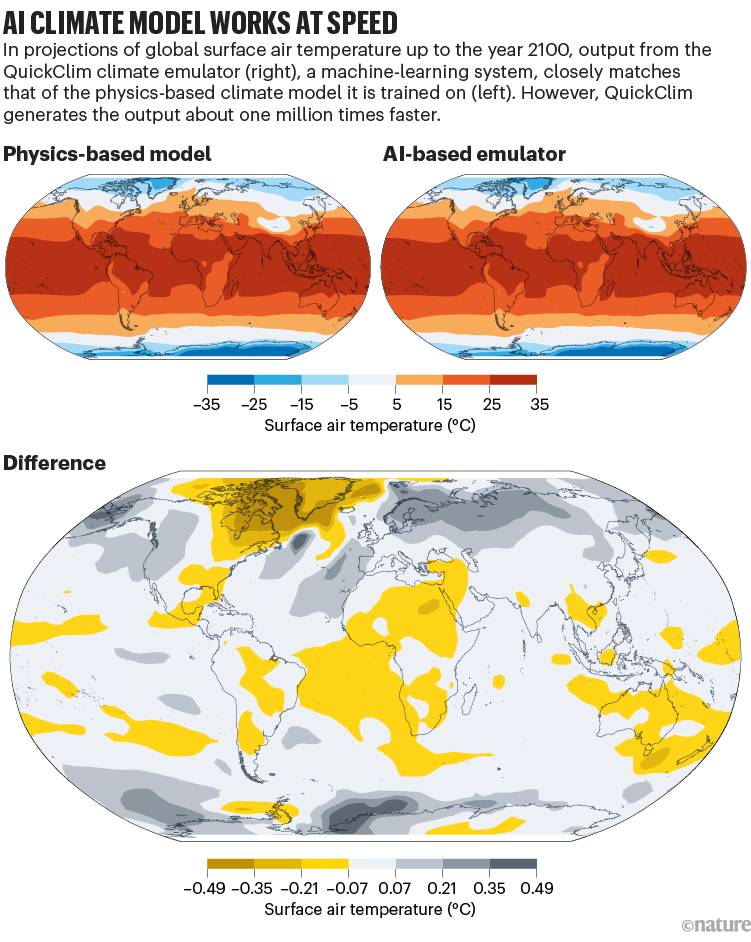

Conventional climate models are built manually from scratch by scientists such as Schneider, who use mathematical equations to describe the physical processes by which the land, oceans and air interact and affect the climate. These models work well enough to make climate projections that guide global policy.

But the models rely on powerful supercomputers, take weeks to run and are energy-intensive. A typical model consumes up to 10 megawatt hours of energy to simulate a century of climate, says Schneider. On average, that is about the amount of electricity used annually by a US household. Moreover, such models struggle to simulate small-scale processes, such as how raindrops form, which often have an important role in large-scale weather and climate outcomes, says Schneider.

Think big and model small

The branch of AI called machine learning — in which computer programs learn by spotting patterns in data sets — has shown promise in weather forecasting and is now stepping in to help with these issues in climate modelling.

“The trajectory of machine learning for climate projections is looking really promising,” says computer scientist Aditya Grover at the University of California, Los Angeles. Similar to the early days of weather forecasting, he says, there is a flurry of innovation that promises to transform how scientists model the climate.

But there are still hurdles to overcome — including convincing everyone that models based on machine learning are getting their projections right.

Copy cats

Researchers are using AI for climate modelling in three main ways. The first approach involves developing machine-learning models called emulators, which produce the same results as conventional models without having to crank through all the mathematical calculations.

Think of a conventional climate model as a computer program that can calculate where a ball will land on the basis of physical factors, such as how hard the ball is thrown, where it is thrown from and how fast it is spinning. Emulators can be considered as equivalent to a sports player who learns the patterns in all those modelled outputs and is then able to predict, without crunching through all the maths, where the ball will land.

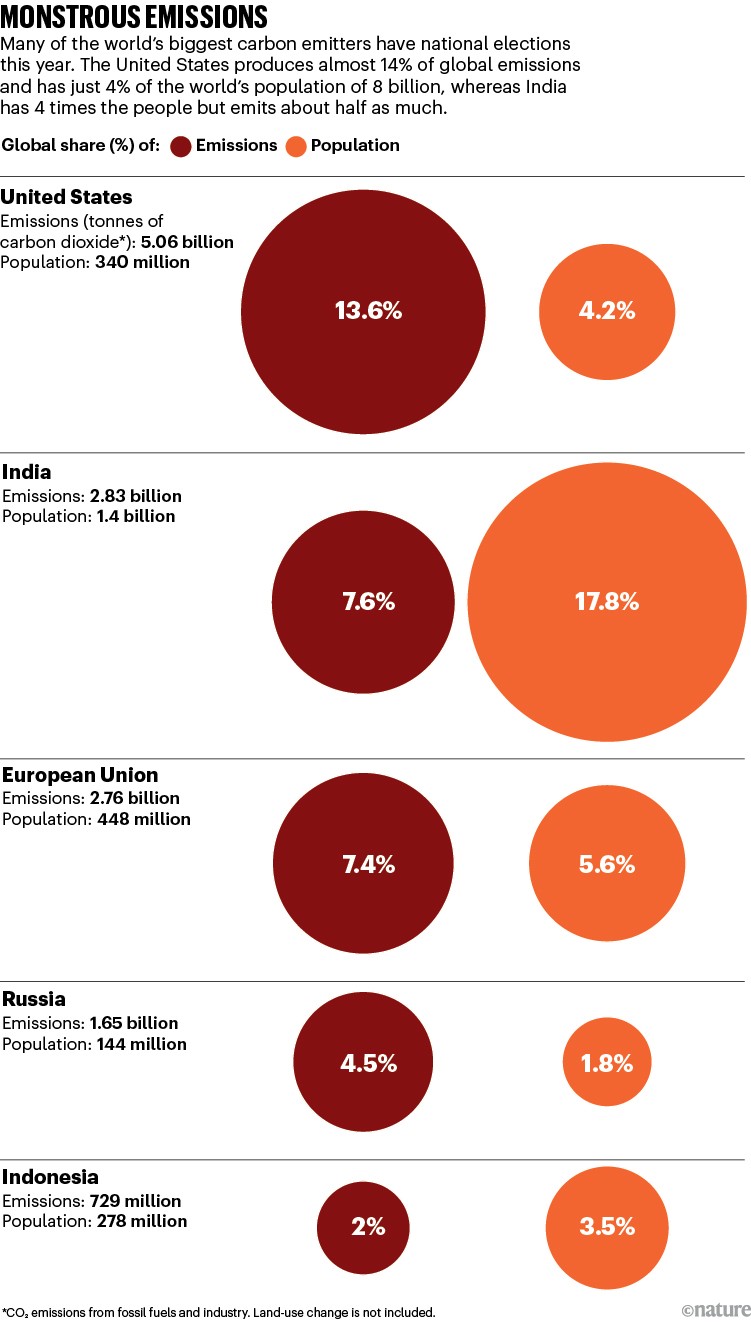

In a 2023 study, climate scientist Vassili Kitsios at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation in Melbourne, Australia, and his colleagues developed 15 machine-learning models that could emulate 15 physics-based models of the atmosphere1. They trained their system, called QuickClim, using the physical models’ projections of surface air temperature up to the year 2100 for two atmospheric carbon concentration pathways: a low and a high carbon emission scenario. Training each model took about 30 minutes on a laptop, says Kitsios. Researchers then asked the QuickClim models to forecast temperatures under a medium carbon emission scenario, which the models had not seen during training. The results closely matched those of the conventional physics-based models (see ‘AI climate model works at speed’).

Source: Ref. 1

Once trained with all three emissions scenarios, QuickClim could quickly predict how global surface temperatures would change during the century under many carbon emission scenarios — about one million times faster than the conventional model could, says Kitsios. “With traditional models, you have less than five or so carbon concentration pathways you can analyse. QuickClim now allows us to do many thousands of pathways — because it’s fast,” he says.

QuickClim could one day help policymakers by exploring multiple scenarios, which would take conventional approaches simply too long to simulate. Models such as QuickClim will not replace physics-based models, Kitsios says, but could work alongside them.

Another team of researchers, led by atmospheric scientist Christopher Bretherton at the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence in Seattle, Washington, developed a machine-learning emulator for one physics-based atmospheric model. In a 2023 preprint study2, the team first created a training data set for the model, called ACE, by feeding ten sets of initial atmospheric conditions into a physics-based model. For each set, the physics-based model projected how 16 variables, including air temperature, water vapour and windspeed, would change over the next decade.

How machine learning could help to improve climate forecasts

After training, ACE was able to iteratively use estimates from 6 hours earlier in its projections to make forecasts 6 hours ahead, over a time span of up to a decade. And it performed well: better than a pared-down version of the physics-based model that runs at half the resolution to save on time and computing power. In that comparison, ACE more accurately predicted the state of 90% of the atmospheric variables, ran 100 times faster and was 100 times more energy-efficient.

Study author and climate scientist Oliver Watt-Meyer at the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence says he was surprised. “I was impressed by the result. These early findings suggest that we’ll be able to make these models that are very fast, accurate and able to probe a lot of different scenarios,” he says.

Firm foundations

In the second approach, researchers are using AI in a more fundamental way, to power the guts of climate models. These ‘foundation’ models can later be tweaked to perform a wide range of downstream climate- and weather-related tasks.

Foundation models hinge on the idea that there are fundamental, possibly unknown, patterns in the data that are predictive of the future climate, says Grover. By picking up on these hidden patterns, the hope is that foundation models might be able to churn out better climate and weather predictions than conventional approaches can, he says.

In a 2023 paper3, Grover and researchers at the tech giant Microsoft built the first such foundation model, called ClimaX. It was trained on the output from five physics-based climate models that simulated the global weather and climate from 1850 to 2015, including factors such as air temperature, air pressure and humidity, simulated on timescales from hours to years. Unlike emulator models, ClimaX was not trained towards the specific task of mimicking an existing climate model.

After this general training, the team fine-tuned ClimaX to perform a wide range of tasks. In one, the model predicted the average surface temperature, daily temperature range and rainfall worldwide from input variables of carbon dioxide, sulphur dioxide, black carbon and methane levels. This task was proposed in 2022 as a benchmark for comparing AI climate models, in a study by atmospheric physicist Duncan Watson-Parris at the University of California, San Diego, and his colleagues4. ClimaX predicted the state of temperature-related variables better than did three climate emulators built by Watson-Parris’s team3. However, it performed less well than the best of these three emulators in predicting rainfall, says Grover.

Science and the new age of AI: a Nature special

“I like the idea of foundation models,” says Watson-Parris. But these early findings don’t yet prove that ClimaX can outperform conventional climate models, or that foundation models are intrinsically superior to emulators, he adds.

In fact, it will be difficult to convince people that any machine-learning model can outperform conventional approaches, says Schneider. The true state of the future climate is unknown and we can’t wait for decades to see how well the models are performing, he says. Testing climate models against past climate behaviour is useful, but not a perfect measure of how well they can predict a future that’s likely to be vastly different from what humanity has seen before. Perhaps if models get better at seasonal weather prediction, they’ll be better at long-term climate predictions, too, says Schneider. “But to my knowledge, that’s not yet been demonstrated and that’s no guarantee,” he says.

Moreover, it is hard to interpret the way in which many of the AI models work, a problem known as the the black box of AI, which could make it hard to trust them. “With climate projections, you absolutely need to trust the model to extrapolate,” says Watson-Parris.

Best of both

A third approach is to embed machine-learning components inside physics-based models to produce hybrid models — a sort of compromise, says Schneider.

Snow cover is hard for conventional climate models to predict, but hybrid models that blend machine-learning and physics-based techniques have successfully simulated snow cover and other small-scale processes.Credit: Mario Tama/Getty

In this case, machine-learning models would replace only the parts of conventional models that work less well — typically the modelling of small-scale, complex and important processes such as cloud formation, snow cover and river flows. These are a “key sticking point” in standard climate modelling, says Schneider. “I think the holy grail really is to use machine learning or AI tools to learn how to represent small-scale processes,” he says. Such hybrid models could perform better than purely physics-based models, while being more trustworthy than models built entirely from AI, he says.

In this vein, Schneider and his colleagues have built physical models of Earth’s atmosphere and land that contain machine-learning representations of a handful of such small-scale processes. They perform well, he says, in tests of river-flow and snow-cover projections against historical observations5. “We’ve found machine-learning models can be more successful than physical models in simulating certain phenomena,” says Schneider. Watson-Parris agrees with that assessment.

By the end of the year, Schneider and his team hope to complete a hybrid model of the ocean that can be coupled to the atmosphere and land models, as part of their Climate Modeling Alliance (CliMA) project.

Similar efforts to create ‘digital twins’ of Earth are being developed by NASA and the European Commission. The European project, called Destination Earth (DestinE), is entering its second phase in June this year, in which machine learning will have a key role, says Florian Pappenberger, who leads the forecast department at the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts in Reading, UK.

The ultimate goal, says Schneider, is to create digital models of Earth’s systems, partly powered by AI, that can simulate all aspects of the weather and climate down to kilometre scales, with great accuracy and at lightning speed. We’re not there yet, but advocates say this target is now in sight.

[ad_2]

Source Article Link