[ad_1]

Credit: Hulton Archive/Getty

Roger Guillemin identified the molecules in the brain that control the production of hormones in endocrine glands such as the pituitary and thyroid. His work led to a torrent of advances in neuroendocrinology, with far-reaching effects on studies of metabolism, reproduction and growth. For his discoveries on peptide-hormone production in the brain, Guillemin shared the 1977 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Andrew Schally and Rosalyn Yalow. He has died at the age of 100.

In the autumn of 1969, after analysing millions of sheep brains for more than a decade, Guillemin and his colleagues determined the structure of thyrotropin-releasing factor (TRF). This small peptide is produced in the hypothalamus, a small region at the base of the brain, and is transported to the anterior lobe of the nearby pituitary gland, where it triggers the release of the hormone thyrotropin. Thyrotropin, in turn, stimulates the thyroid gland to produce the hormone thyroxine, which regulates metabolic activity in nearly every tissue of the body. More than two dozen drugs use such hypothalamic hormones to treat endocrine disorders and cancers, and the worldwide market for these drugs is worth several billion dollars.

Guillemin was born in Dijon, France, and came of age at the end of the Second World War. He graduated from medical school in the University of Lyon, France, in 1949 and worked as a country doctor in the small commune of Saint-Seine-l’Abbaye in Burgundy. He found the work satisfying but intellectually limiting, noting that “in those days I could take care of all my patients with three prescriptions, including aspirin”. Fascinated by how the brain and pituitary gland control the body’s response to stress, he attended lectures in Paris by the Hungarian–Canadian endocrinologist Hans Selye, after which Selye accepted Guillemin’s request to spend a year doing research in his laboratory at the University of Montreal, Canada.

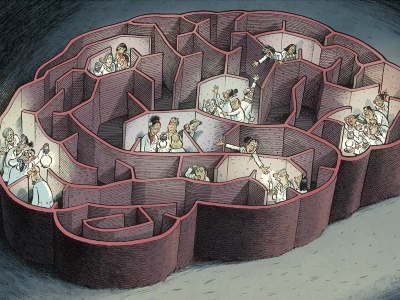

The consciousness wars: can scientists ever agree on how the mind works?

This turned into a four-year project, for which Guillemin was awarded a PhD in 1953. His studies with Selye were impactful, but it was meeting the UK physiologist Geoffrey Harris in Canada that would shape Guillemin’s subsequent science. Harris argued that the hypothalamus controls the anterior pituitary not through nerve signals, but rather through blood-borne factors that reach the pituitary through the capillaries of an interconnecting stalk. Recruited to the faculty of the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, Guillemin decided to tackle Harris’s hypothesis head on. His initial aim was to purify and determine the structure of corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), the hypothalamic hormone that stimulates the anterior pituitary to produce adrenocorticotropic hormone, the driver of the stress response described by Seyle. Progress towards this goal was slow, so Guillemin turned his attention to other putative releasing factors, including TRF.

The scale of his efforts at purification in the late 1950s and 1960s was enormous. These releasing factors were peptides — short chains of amino acids — present in only tiny amounts in the hypothalamus. Together with the fact that the hypothalamus is itself a small part of the brain, this meant that purification began with extracts prepared from millions of sheep hypothalami obtained from slaughterhouses. Peptides were separated on 3-metre-tall chromatography columns that extended through the lab’s ceiling. One set of columns was packed with the then-new resin Sephadex, released by the Stockholm-based biotechnology company Pharmacia in 1959. Guillemin sent a postdoc in his lab, Andrew Schally, that year to Sweden to procure much of the world’s supply of Sephadex.

Schally, who had worked on releasing factors for his PhD, joined the expanding team in Houston in 1957. He chafed under Guillemin’s leadership, however, viewing his years in Houston as a struggle in which he and Guillemin had a “very bitter, unpleasant relationship”. Guillemin suggested that Schally should move on, and himself accepted a simultaneous appointment at the Collège de France in Paris in 1960. Schally established his own competing research operation at Tulane University in New Orleans, Louisiana. Guillemin and Schally would remain competitors for more than two decades, a state of affairs not changed by their shared Nobel Prize.

Signs of ‘transmissible’ Alzheimer’s seen in people who received growth hormone

The Houston and New Orleans teams succeeded in purifying TRF and determining its amino-acid sequence at around the same time. Immediately thereafter, Guillemin moved his lab to the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, California. There, his team identified a raft of hypothalamic releasing factors, now referred to as hormones. These included gonadotropin-releasing hormone, which drives the release of hormones that stimulate the reproductive organs; somatostatin, which inhibits the release of growth hormones; and growth-hormone-releasing hormone. In 1981, a Salk Institute team headed by US endocrinologist Wylie Vale, who was a student of Guillemin, finally purified and sequenced the elusive CRF, Selye’s obsession and Guillemin’s initial target from the 1950s. Drugs built on these discoveries have proved to be among the farthest-reaching medical translations of research from the institute.

Guillemin was the recipient of multiple honours and awards as well as the Nobel Prize. He was a connoisseur of the wines of Burgundy, and during his tenure as president of the Salk Institute in 2007–09, white wine was served at lunchtime faculty meetings. Roger lived an art- and music-filled life, and was close to the artists Françoise Gilot and Niki de Saint Phalle. He cherished his ties to family, students, postdocs, colleagues and friends. He leaves a vibrant scientific legacy.

[ad_2]

Source Article Link