The National Portrait Gallery's portrait podcast concludes its fourth season with a look at Ms. – "More than a magazine, a movement", as the label of the publication says. When a preview issue hit newsstands in December 1971, its provocative cover made it clear that this was a magazine that challenged the then-dominant notion that women's publications should be about fashion and weight-loss advice.

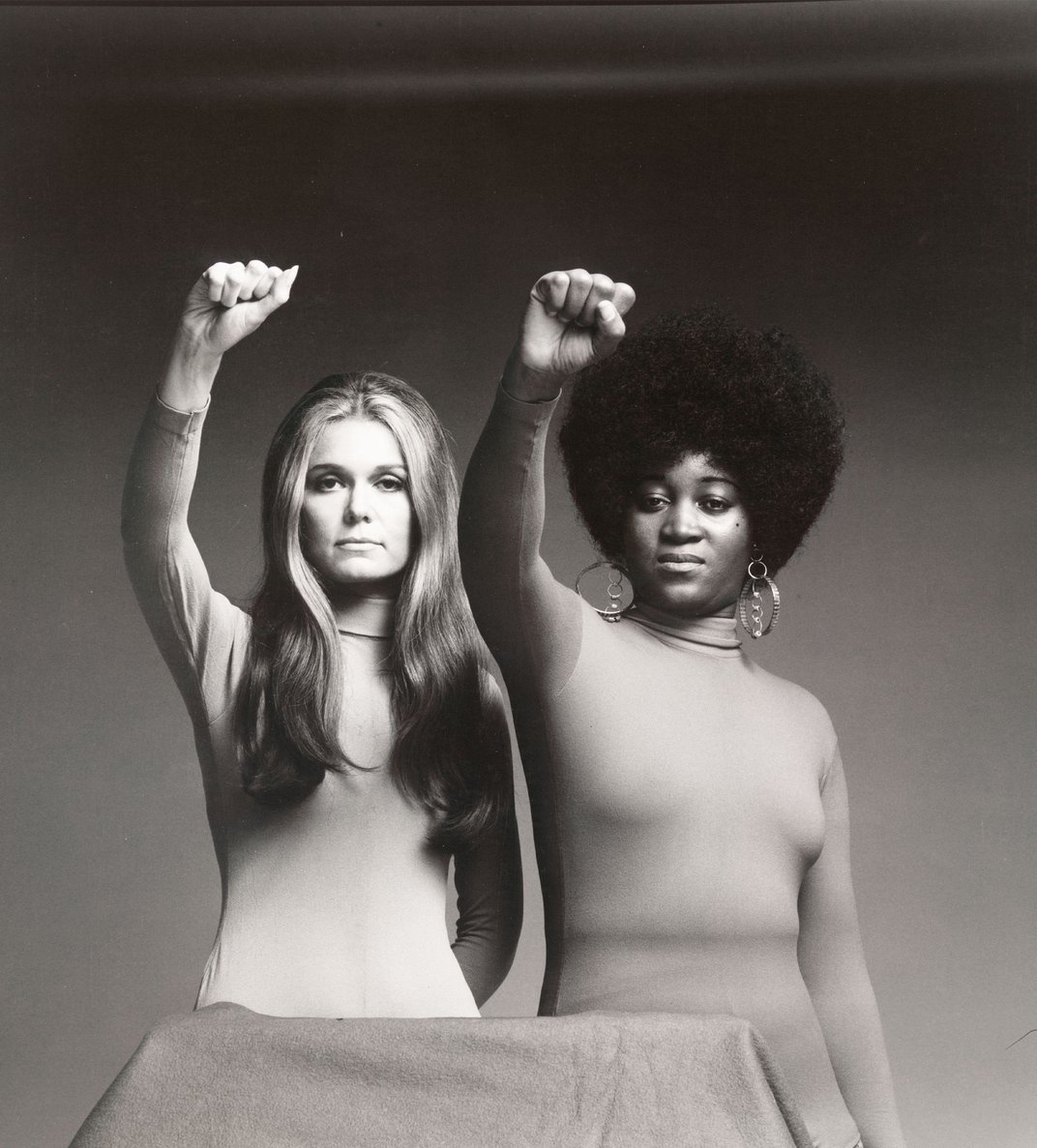

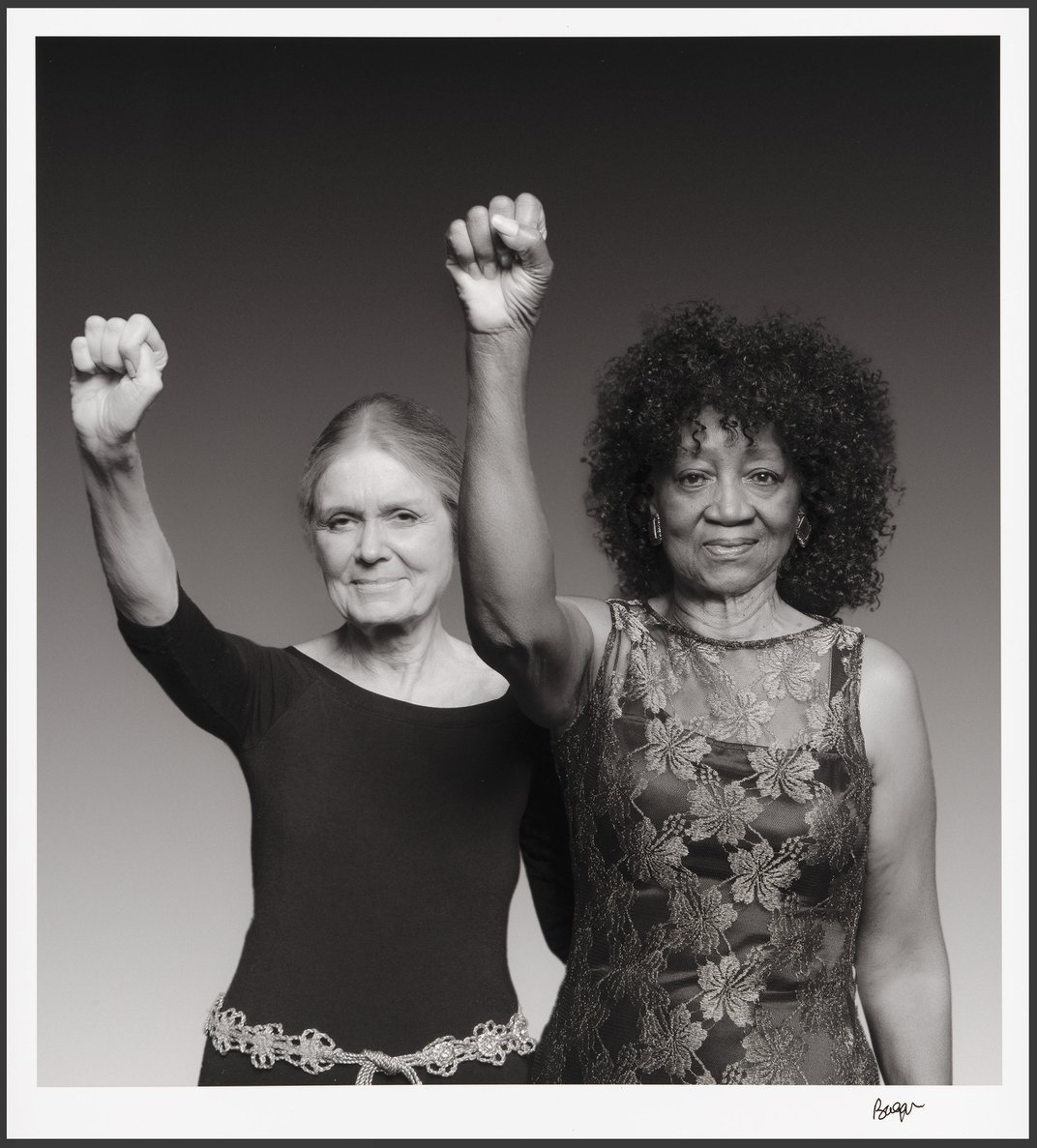

Portrait editor Kim Saget spoke with activist and author Gloria Steinem, co-founder of Ms., and Suzanne Brown Levine, the publication's first editor, for a glimpse into how they decided to bring the feminist magazine to the world.

Having spent much of the 1960s covering sexism in her chosen profession, journalism, Steinem had no interest in creating another publication that would appease advertisers who portrayed women as abstractions, sex objects, bald nurses and posed no threat.

I thought again and realized that if I were to submit the manuscript to the Sunday New York Times , maybe I shouldn't trust my editor to give me a choice: I could go to his hotel room in the afternoon, or I could send the letter. by mail, while I was gone, Steinem told Sajet: "I sent the message, but thanks to a change of conscience, I realized that it was not right to talk about it."

Levine remembers what it was like during his first week at Ms. He was wearing jeans and a t-shirt, and a man in the elevator chided him for his casual clothes not being appropriate for work. However, he tells Sage that he understands that what feels like liberation is a threat and a concern to others.

Saget notes that in 1969, Time magazine referred to women's rights activists as "The Angry Ones." The women were determined to present a broader and more nuanced view of feminism than was reported in mainstream news magazines at the time.

"Anger is always one of the most discouraging and unacceptable responses women have," says Levine. "You know, you walk past construction workers and they say, 'Why aren't you smiling, honey?'

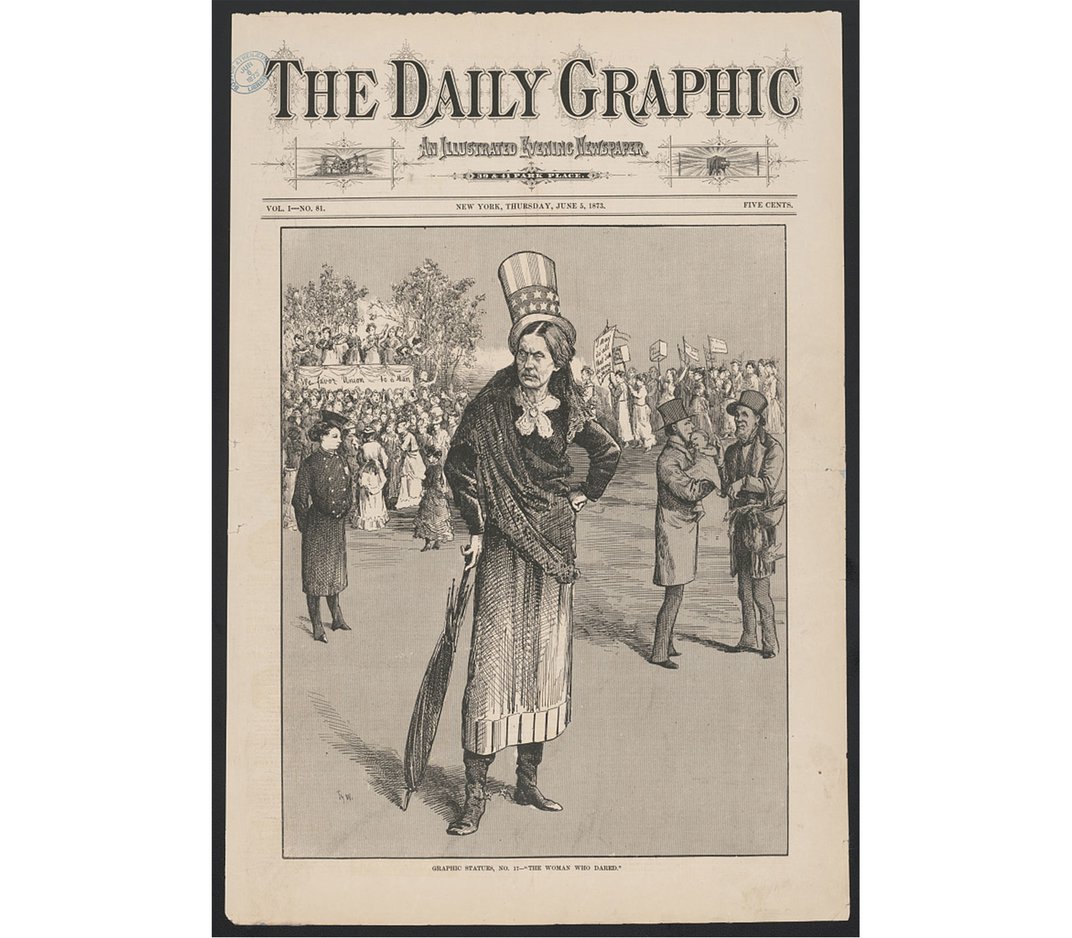

Sajet and Levine discuss how independent women are traditionally portrayed in magazines as brutish and lonely. Levine notes that the illustration of Susan B. Anthony on the cover of the Daily Graphic in 1873 was so unflattering that she looked like an "angry nun."

The first issue of Women featured an article on how to write a prenuptial agreement, an article on how to raise children without exposing them to sexual thoughts, and a shocking story called "We Had Miscarriages" by tennis pro Billie Jean. King, by singer Judy Collins and Steinem herself, along with 50 other leading actresses. The article included an invitation to unsubscribed readers to add their names. This helped convince Levine, who had kept her abortion a secret until then, that the loss was something he wanted to be a part of. After all, he worked for the magazine for 16 years.

How do you present an honest and thoughtful flyer in a market where, as Steinem points out, the idea of even photographing a woman without makeup is unthinkable?

For the cover, she and her colleagues chose artist Miriam Wosk's illustration of a blue-skinned, eight-armed, multitasking pregnant woman dancing in ruby-red heels on a grassy hill, with a black-and-white cat sitting on her right. . the ankle.

The first idea was to try to "get every woman on the cover," Steinem told Sajet. We have [illustrations] of big faces, and the faces have different skin tones. But his face looks very strange. It does not work as an optical image. So Miriam found a way to show a woman inspired by Krishna, the Indian deity with many weapons. Making it blue is one way to make it universal. She has a child in her womb, she has an iron and a typewriter, a mirror that represents her beauty and a telephone. Besides, women have to act, so tears rolled down her cheeks.

Levine provides additional context for the illustration, which shows a woman doing chores and errands at the same time. "It became kind of a symbol, you can have it all," he said. "That shouldn't be the message, because everybody understands that you can have everything, but not everything at the same time. It's almost a way of getting us back to where we can't have everything."

"A picture is worth 1,000 words," the Jan. 12 episode of Aerospace, the National Air and Space Museum's podcast, reveals how human "image processors" process data collected by the James Webb Space Telescope (and observatories of others) and turn them into vivid images, pulsating to life. A fascination that has gripped everyone's mind since NASA began releasing long-range images last July.

"Astronomers like to call telescopes light buckets because they really do collect light," astronomer Shawna Edson told guests Emily Martin and Matt Schindel.

The James Webb Space Telescope, to follow suit, not only observes the Universe from a vantage point inaccessible to humans, orbiting the Sun from an L2 Lagrange point a million miles from Earth. Like an infrared telescope, it collects light in parts of the spectrum that the human eye cannot see. Translating these images into images requires some interpretation, and it is the work of interpretation that provides the colors and patterns that appeal to us so deeply.

For this, the images are interpreted , but no less realistically. These are difficult things to understand, but Edson gives the listeners a clear and convincing explanation: "It's not what your eyes will see, but it's all real light. We haven't found anything. We get these data, this information, the light that these telescopes collect for us… and we see it." ".

"We colorize," he adds, to improve human understanding of the image. "Color is not what our eyes see, but information, data and light are all real… We're just amplifying what's already there. So we can make hydrogen and oxygen red green around us for help us see. : Where." are they [elements] in the mist? How did the star explode?" Where are the different temperatures? Your eyes will not see it.

The episode builds on its title "A picture is worth 1,000 words" by discussing alternative text and other tools aimed at making visual documents such as astronomical images accessible to the blind or partially sighted.

Martin and Schindel read examples of flowery and even poetic alternative texts and compare them to more utilitarian texts. There is no wrong version. One is somewhat more subjective and a more generous evaluator than the other. Schindel reminds us that not everything in science is science. There is also room for poetry.

The Smithsonian Institution offers a variety of podcasts for all listeners.

recommended videos

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/equal-opportunity-3094913x-56aa24e35f9b58b7d000fc1f.jpg)