[ad_1]

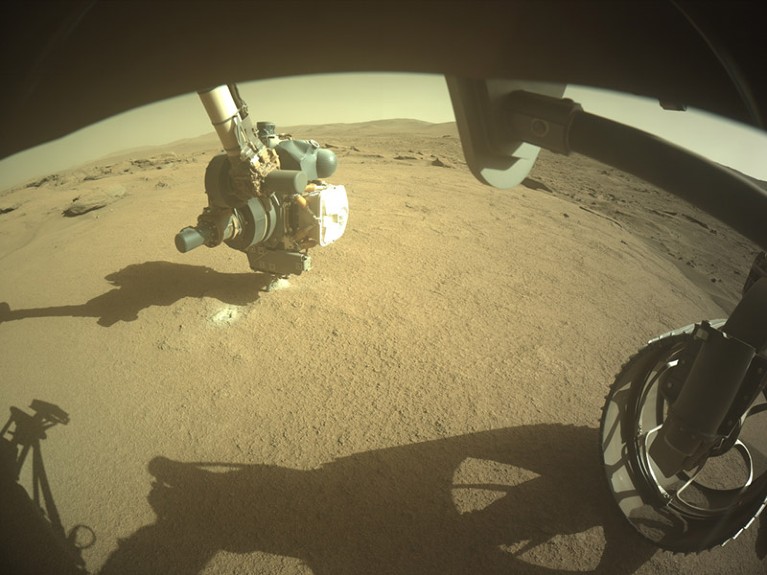

A pig kidney is unpacked for transplant into 62-year-old Richard Slayman of Massachusetts.Credit: Massachusetts General Hospital

Early success in the first transplant of a pig kidney into a living person has raised researchers’ hopes for larger clinical trials involving pig organs. Such trials could bring ‘xenotransplantation’, the use of animal organs in human recipients, into the clinic.

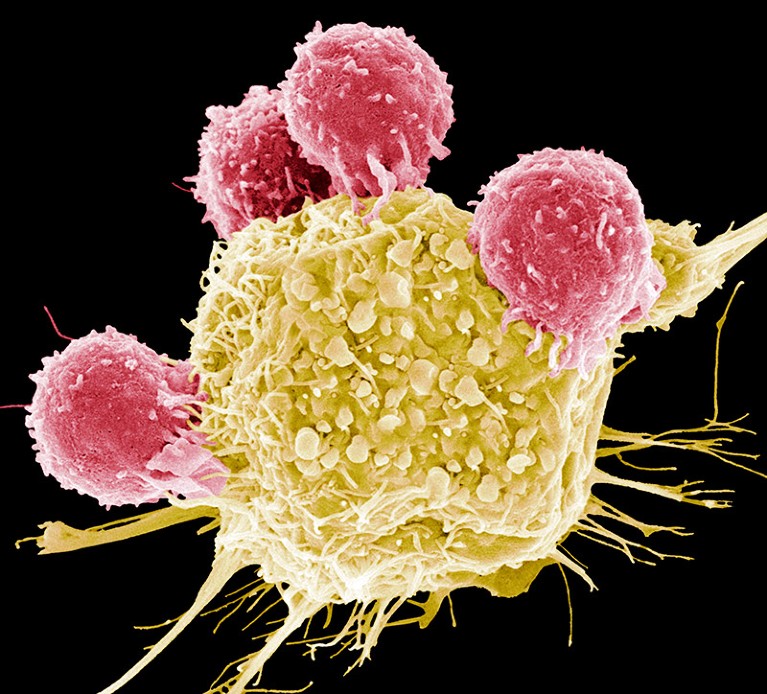

The recipient of the pig kidney was a 62-year-old man with end-stage renal failure named Richard Slayman. He is recovering well after his surgery on 16 March, according to his transplant surgeon. The kidney was taken from a miniature pig carrying a record 69 genomic edits, which were aimed at preventing rejection of the donated organ and reducing the risk that a virus lurking in the organ could infect the recipient.

Monkey survives for two years after gene-edited pig-kidney transplant

The case demonstrates that, at least in the short term, these organs are safe and function like kidneys, says Luhan Yang, chief executive of Qihan Biotech in Hangzhou, China, who is also a founder of the biotech firm that produced the pigs, eGenesis in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The company is in discussions with the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) about planning clinical trials for its programmes for transplanted pig kidneys, livers and paediatric hearts, says Wenning Qin, a molecular biologist at eGenesis.

Hopes for full-scale tests

All US transplants of animal organs into living humans, including Slayman’s, received FDA approval as a ‘compassionate use’, granted in narrow cases when a person’s life is at risk and there are no other treatments. But Yang hopes that the new results will push the FDA towards approval of full-scale clinical trials. Xenotransplants can “provide hope and life for patients and their families”, Yang says.

The surgery also brings clinicians closer to relieving the shortage of life-saving human organs by using animal organs. In the United States alone, there are nearly 90,000 people waiting for a kidney transplant, and more than 3,000 people die every year while still waiting. “Even though organ donation rates have increased massively, we still need millions of organs to transplant into patients,” says Wayne Hawthorne, a transplant surgeon at the University of Sydney in Westmead, Australia.

“This is great news for the field,” says Muhammad Mohiuddin, a surgeon and researcher at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore, who led the first pig-heart transplant in a living person. Mohiuddin, who is also president of the International Xenotransplantation Association, says clinical trials would produce much-needed rigorous data about the safety and efficacy of xenotransplantation.

Surgeons have previously transplanted gene-edited pig hearts into two living people. And modified kidneys have been transplanted into several people declared dead because they lack brain function. Earlier this week, surgeons in China transplanted a modified pig liver into a clinically dead person and kept the organ in place for ten days.

Dozens of edits

The operation to give Slayman a pig kidney took four hours, says Tatsuo Kawai, one of the transplant surgeons who conducted the surgery. On his right side, Slayman retained a donated human kidney that Kawai had transplanted into him in 2018, but that had begun to fail. As a result, Slayman had resumed regular dialysis, but he developed complications that required frequent hospital visits, which made him a candidate for xenotransplantation.

Surgeons in Boston, Massachusetts, perform the first transplant of a pig kidney into a living person.Credit: Massachusetts General Hospital

Slayman’s newest kidney came from a pig that had undergone CRISPR–Cas9 genome editing by eGenesis’s scientists to modify 69 of the animal’s genes. Monkeys called cynomolgus macaques (Macaca fascicularis) that received the company’s pig organs with these same genomic edits survived for months to years1. Qin says she is hopeful that Slayman’s xenotransplanted kidney will survive for just as long or even longer, particularly because her team devised the edits with humans, not monkeys, in mind.

The edits included removal of three genes that contribute to the production of a protein on the surface of pig cells. The human immune system attacks cells bearing this protein, which it takes as the hallmark of a foreign invader. Seven genes were added because they produce human proteins that help to prevent organ rejection.

Antiviral meaures

Another 59 genetic changes were made to inactivate viruses embedded in the pig genome. These changes address the risk that the viruses will become active once in the human body. So far, researchers have not seen this happen in transplants to living humans, people who are clinically dead or non-human primates, says Yang. But some laboratory experiments have shown that these viruses can be transmitted from pig tissue to human cells and to mice with compromised immune systems2.

First pig-to-human heart transplant: what can scientists learn?

The first genetically modified pig heart to be successfully transplanted into a living person turned out to be tainted with a latent virus, which might have contributed to the organ’s eventual failure3. A major concern for the FDA ahead of approving the operation was the risk that pig pathogens could infect the recipient, Kawai says. eGenesis tests its pigs on a regular basis for pathogens including porcine cytomegalovirus, which can linger quietly in its animal hosts, Qin says.

Before the procedure, the researchers collected and froze blood samples from Slayman, his family members, and his surgeons. If Slayman develops an infection, researchers can test these blood samples to determine whether they were the source of the pathogen, says Kawai.

Slayman will continue to be tested regularly for pathogens, and if he develops symptoms, his family members and caregivers will also be tested.

These precautions are important because a healthy pig is very different to an immunocompromised individual, says Yang. Even though no viruses, bacteria or fungi were detected in the pigs prior to the transplant, they could still be present and grow in an immunocompromised person, she says. “We don’t know what we don’t know.”

Healthy kidney

Kidneys filter out toxic substances from the body, produce urine and help to control blood pressure. Once the surgeons restored blood flow to the transplanted pig organ, it immediately became pink and started to produce urine, says Kawai, a sign that the transplant had been successful.

First pig liver transplanted into a person lasts for 10 days

Another metric of kidney health is the level in the blood of a chemical compound known as creatinine — high levels indicate that the kidney is not performing its waste-filtering role well. Kawai says that prior to the transplant, Slayman’s creatinine level was 10 milligrams per decilitre, but it had gone down to 2.4 by the fourth day. He hopes it will drop to 1.5, which is around the normal range.

“It seems like so far this kidney is functioning the way that it is supposed to,” Mohiuddin says.

Slayman could be released from the hospital as early as tomorrow, Qin says. He is receiving immunosuppressive medications, and has so far shown no signs of organ rejection. Qin says that eGenesis’s goal is to find the right combination of genetic edits in pigs to make it unnecessary for organ recipients to take immunosuppressive drugs, which weaken the body’s ability to fight off pathogens.

“There was always a saying that xenotransplantation is around the corner, and will always be,” Qin says. “Well, now we have someone among us that carries a porcine kidney — it’s just amazing.”

[ad_2]

Source Article Link