[ad_1]

Hello Nature readers, would you like to get this Briefing in your inbox free every week? Sign up here.

The insect wing hinge is one of the most sophisticated skeletal structures in the animal kingdom. (Johan M. Melis et al/Nature)

A machine-learning model that can fly like a fly helped researchers to unravel the workings of the insect wing hinge. Most hypotheses about this complex biomechanical structure have been built on how it looks when it isn’t moving. An AI system, trained on video recordings of around 70,000 fruit-fly wing beats, predicted how muscle contractions would cause different wing motions. A winged robot programmed with the model’s findings then allowed the researchers to create a map linking muscle activity to flight forces.

An AI tool could help to identify the origins of cancers that have spread from a previously undetected tumour somewhere else in the body. The proof-of-concept model analyses images of cells from the metastatic cancer to spot similarities with its source — for example, breast cancer cells that migrate to the lungs still look like breast cancer cells. In dry runs, there was a 99% chance that the correct source was included in the model’s top three predictions. A top-three list could reduce the need for invasive medical tests and help clinicians tailor treatments to suit.

Reference: Nature Medicine paper

An initiative called ChatGPT and Artificial Intelligence Natural Large Language Models for Accountable Reporting and Use (CANGARU) is consulting with researchers and major publishers to create comprehensive guidelines for AI use in scientific papers. Some journals have introduced piecemeal AI rules, but “a standardized guideline is both necessary and urgent”, says philosopher Tanya De Villiers-Botha. CANGARU hopes to release their standards, including a list of prohibited uses and disclosure rules, by August and update them every year.

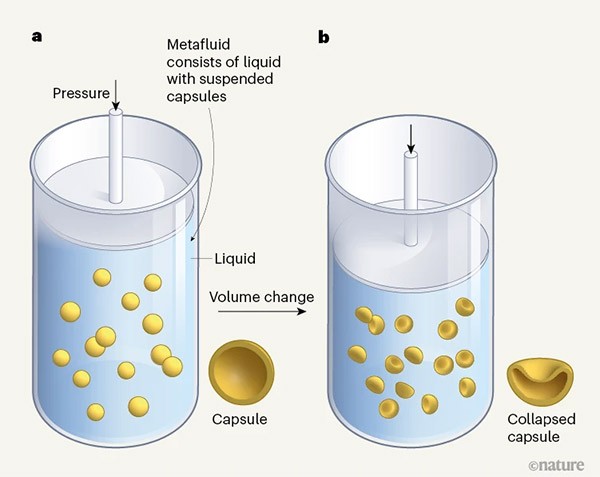

Infographic of the week

This ‘metafluid’ can be used to build robotic grippers that can grasp objects as large and heavy as a glass bottle — or as small and fragile as an egg. Unlike a regular liquid, the metafluid can be compressed: the small gas-filled capsules collapse when pressure increases. The pressure inside the material then plateaus for some time even if outside pressure increases further. This means that when the system is used to operate a gripper, applying the same pressure will grasp objects of various sizes and fragility. (Nature | 7 min read, Nature paywall)

Reference: Nature Reviews Materials paper

Features & opinion

AI systems could reveal hidden features in medical scans that currently require injecting dyes into the body. Contrast agents — gadolinium for magnetic resonance imaging, for example — are generally safe, but aren’t suitable for people with certain conditions. AI-assisted virtual dyes also make images taken with a fluorescence microscope appear as if they had been stained by a pathologist, a process that makes features stand out. Radiologist Kim Sandler expects to spend less time writing reports about what she sees in scans, and more time vetting AI-generated reports. “My hope is that it will make us better and more efficient, and that it’ll make patient care better,” Sandler says.

This article is part of Nature Outlook: Medical diagnostics, an editorially independent supplement produced with financial support from Seegene.

If neural networks mull over their training data for too long, they end up memorizing the information and become worse at adapting to unseen test data. But when researchers accidentally overtrained a model that specialized in certain mathematical operations, they discovered that it could suddenly master any test data. This ability, called ‘grokking’ — slang for total understanding — seems to happen when the system develops a unique way to solve problems. It’s not yet clear if this phenomenon applies to AI models beyond small, specialized ones. “These weird [artificial] brains work differently from our own,” says AI researcher Neel Nanda. “We need to learn to think how a neural network thinks.”

When a study that pitted 256 humans against three chatbots, the AI systems were generally more creative at coming up with uncommon uses for everyday objects. The study adds to an ongoing debate about how machines master skills traditionally considered to be exclusive to people. Passing tests designed for humans doesn’t demonstrate that machines are capable of anything approaching original thought, AI researcher Ryan Burnell points out. Chatbots are fed vast amounts of mostly unknown data and might just draw on things seen in their training data, he suggests.

MIT Technology Review | 5 min read

Reference: Scientific Reports paper

Today, I’m bidding farewell to Boston Dynamic’s iconic humanoid robot Atlas, which is being decommissioned after 11 years of running, jumping, flips and falls. The hydraulic machine will be replaced by a new electric Atlas model with a fully rotating ‘head’ and reversible ‘hips’ that allow it to easily get up from the ground.

Please tell me about your favourite robot (real or fictional) by sending an e-mail to [email protected].Thanks for reading,

Katrina Krämer, associate editor, Nature Briefing

With contributions by Flora Graham

Want more? Sign up to our other free Nature Briefing newsletters:

• Nature Briefing — our flagship daily e-mail: the wider world of science, in the time it takes to drink a cup of coffee

• Nature Briefing: Anthropocene — climate change, biodiversity, sustainability and geoengineering

• Nature Briefing: Cancer — a weekly newsletter written with cancer researchers in mind

• Nature Briefing: Translational Research covers biotechnology, drug discovery and pharma

[ad_2]

Source Article Link