[ad_1]

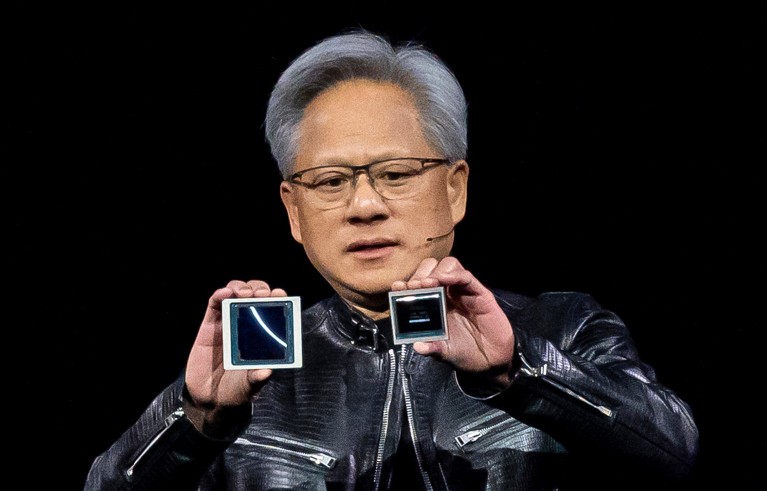

Nvidia chief executive officer Jensen Huang shows off the new Blackwell GPU chip (left) at an 18 March event in San Jose, California.Credit: David Paul Morris/Bloomberg via Getty

The rapid advance of generative artificial intelligence (AI) has sparked a global technological race to produce computer chips that power the models. A US ban on selling high-quality computer chips to China is stifling the country’s progress in key technologies, according to researchers both inside and outside the country.

The chips have become increasingly crucial to power the latest advances in generative artificial intelligence (AI). “Generative AI could change society,” says Yiran Chen, an electrical and computer engineer at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. “If China is isolated, it’s not able to catch up.”

In the past few years, interest in AI has exploded as a result of progress in generative AI tools — large language models that can produce original text, video or audio content based on human-generated input. Such models underlie technology including OpenAI’s chatbot ChatGPT and Microsoft’s digital assistant Copilot.

The AI boom has also sparked a global race to produce increasingly powerful computer chips that can cope with the large data sets needed to train and execute models. Nvidia, one of the leading developers of such chips, based in Santa Clara, California, has seen its market value shoot past US$2 trillion for the first time last March. “The US is ahead of almost every single country because of companies like Nvidia and AMD,” says Ahmed Banafa, an engineer at San Jose State University in California.

Export controls imposed by the US Department of Commerce in October 2022, and subsequently tightened a year later, prohibited the sale of certain technologies to China, including chips that can operate above speeds of 300 teraflops, or 300 trillion operations per second. It also limited the sale of state-of-the art manufacturing equipment that could be used to produce such chips. The United States was acting because China “has poured resources into developing supercomputing capabilities and seeks to become a world leader in artificial intelligence by 2030. It is using these capabilities to monitor, track, and surveil their own citizens, and fuel its military modernization,” said a statement from the US government accompanying the export controls.

The ban has “dramatically limited” China’s progress with training AI models, says Chen.

“We cannot get high-end Nvidia chips in China and we cannot fabricate high-end chips,” says Yu Wang, an electronic engineer at Tsinghua University in Beijing.

Supply stagnation

Many suppliers outside the Chinese mainland, such as the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) in Hsinchu, which produces chips for Nvidia and other US developers, will not sell its most advanced chips to China to avoid falling foul of US sanctions. “For China, TSMC can only fabricate chips below the bar of the regulations”, meaning the 300-teraflop limit set by the Biden administration, says Wang. “So China can only do their own high computing-power chips inside China.”

China’s leading competitor to Nvidia, Huawei, has sought to develop its own AI chips, but Banafa says China is still “at least five to ten years” behind the United States, partly because it cannot get access to the most advanced equipment needed to produce such chips.

Generations of chip design are labelled according to nanometre ratings, with smaller numbers denoting more advanced chips. Nvidia’s latest chip — the GB200 Blackwell, intended to sell at $30,000–$40,000 per chip according to chief executive Jensen Huang — has gaps of just four nanometres, approaching the width of a strand of human DNA.

Nvidia and other US companies, such as Intel, along with Samsung in South Korea, are now transitioning to 3 nm technology and even pushing down towards 2 nm. “When you go down, you can add more transistors and more power,” says Banafa.

China’s best efforts, from Huawei, are still at around 7 nm, meaning that Chinese companies have to use more chips to achieve the same computing power as one advanced chip. “Until they have a technology breakthrough that will take them lower, they’re [playing] catch-up to the US,” says Banafa.

Other avenues

Jenny Xiao, a partner at the research-focused AI investment fund Leonis Capital in San Francisco, California, says a “black market” for high-end chips has developed in China. “If you say ‘I want to buy 5,000 chips,’ it’s hard not to get noticed,” she says. “But if you’re a smaller start-up, it doesn’t really affect you.”

There has been some good news for Chinese chip development — using AI itself to design computer chips. Yunji Chen, a computer scientist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences Institute of Computing Technology in Beijing, and his colleagues said in the past year that they have developed the first chip to be designed by AI without human input1, called Enlightenment-1. “I believe that in five or ten years, AI can design chips as good as human beings,” says Chen. “If you want to design an AI chip, traditionally you need three years and 1,000 people. But if you use AI, you just need several hours. If this cycle becomes real, how AI evolves will be much faster.”

But for the time being, China is finding itself increasingly isolated as AI chip development continues apace elsewhere. “Who’s going to use a chip fabricated by China?” says Yiran Chen. “It’s a commercial war.”

A lack of competitiveness in AI could exacerbate what some describe as a brain drain in the country. “The broader issue is the economy,” says Xiao. “Most ambitious Chinese students want to go abroad and stay. They’re not thinking about being in China.”

[ad_2]

Source Article Link