[ad_1]

Nations worldwide are aiming to introduce some of the tightest restrictions ever on smoking and vaping, especially among young people.

In one of the world’s most ambitious plans, UK lawmakers on 16 April backed a proposal to create by 2040 a ‘smoke-free’ generation of people who will never be able to legally buy tobacco. The UK, Australian and French governments are also clamping down on vaping with e-cigarettes. These countries’ bold policies are currently in the minority, say researchers, but such measures would almost certainly prevent diseases, as well as save lives and billions of dollars in health-care costs.

Smoking scars the immune system for years after quitting

The UK plan would probably “be the most impactful public-health policy ever introduced”, says health-policy researcher Duncan Gillespie at the University of Sheffield, UK. The proposal, initiated by the Conservative government’s Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, is a step closer to becoming law. The government hopes that smoking restrictions, alongside offering health benefits for individuals, will reduce toxic chemicals leaching from used vapes into the environment.

Smoke-free generations

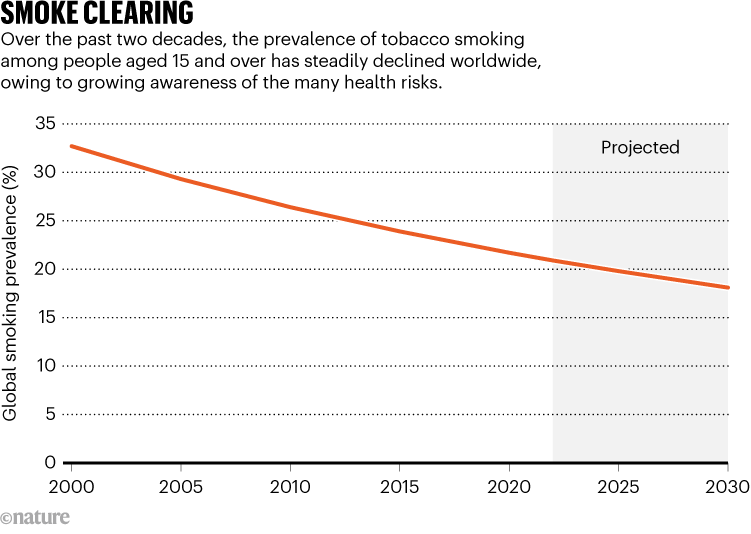

The health harms of smoking tobacco have been established for decades — it substantially raises the risk of diseases including cancer, heart disease and diabetes. Increased awareness of these health risks has led to a global decline in the deadly habit in the past few decades (see ‘Smoke clears’).

Source: WHO

Any drop in smoking rates saves money and reduces the burden on health-care systems, says Alison Commar, who studies tobacco policy at the World Health Organization (WHO) in Geneva, Switzerland. The WHO estimates that tobacco use costs the world US$1.4 trillion every year in health expenditures and lost productivity. “Every tobacco-related illness is adding to the burden on the health system unnecessarily,” says Commar.

The UK proposal, announced last October, would ban the sale of tobacco to any person born in or after 2009. That would prevent anyone who turns 15 or younger this year from ever buying cigarettes legally in the country. From 2027, the minimum legal age to purchase tobacco products would increase from 18 years old by one year each year — meaning that the threshold in 2028, for instance, would be 20. This strategy, the government hopes, will by 2040 create a smoke-free generation. The UK move follows similar legislation announced in 2021 by New Zealand. The nation reversed its intended ban because tobacco sales were needed to help pay for tax cuts, but the government said last month that it will seek to ban disposable vapes.

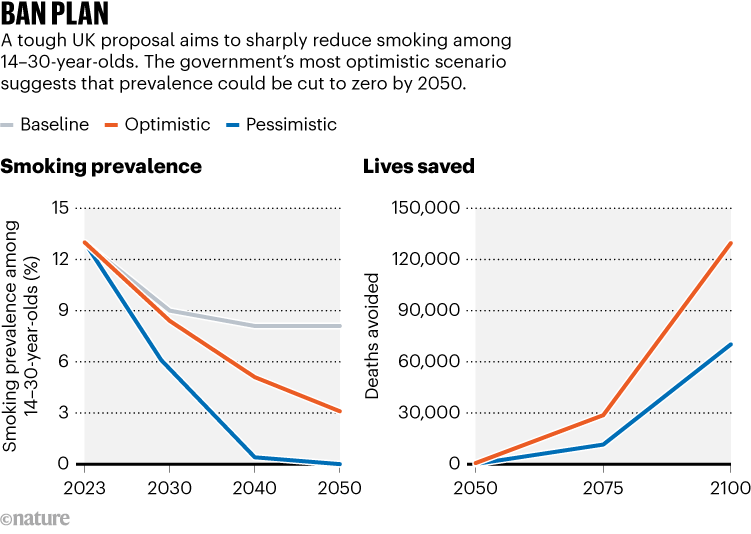

Modelling smokers

The UK government’s policies are backed by a modelling study published in December that predicts how the proposal would affect smoking rates and people over time. Its ‘pessimistic’ model predicts that the policy could reduce the smoking rate among people aged 14–30 from 13% in 2023 to around 8% in 2030. By 2040, just 5% of this age group would smoke. In the baseline scenario, 8% of 14- to 30-year-olds would smoke. In the ‘optimistic’ scenario, only 0.4% of that age group would start smoking by 2040 (see ‘Ban plan’). That model suggests that, by 2075, the policy would save tens of thousands of lives and £11 billion ($13.7 billion) in health-care costs by preventing smoking-related diseases.

These projections are based on solid evidence and are of high quality, says tobacco researcher Allen Gallagher at the University of Bath, UK.

Still, no country has ever introduced a policy that raises the minimum tobacco-purchasing age in this way — only time will tell what the effects will be, says Commar.

Vaping bans

Nations are also targeting vaping, a trend that began around 2010 and has surged among younger people. Many people have perceived it as a potentially healthier alternative to smoking — for which there is substantial evidence. But whether vaping itself harms health has long been controversial, and the evidence is uncertain.

“The results are not super clear, but certainly hint towards vaping causing damage to the lungs and other organs,” says Carolyn Baglole, who studies lung disease at the McGill University Health Centre in Montreal, Canada.

Source: UK government

Vapes are made of a box filled with liquid that usually contains nicotine, a heating element that turns the liquid into aerosols and a mouthpiece to inhale the aerosol ‘vape’ clouds, which are often fruity or dessert-flavoured. Although vapes lack tobacco and most of the toxic chemicals in cigarettes, the nicotine is still harmful. Nicotine can raise blood pressure, increase the risk of heart and lung disease and disrupt brain development in children and adolescents. In turn, this can lead to impairments in attention, memory and learning.

The UK plan includes banning disposable vapes, restricting vape flavours that appeal to young users and limiting how vapes are advertised. Most young people in Great Britain use disposable vapes rather than rechargeable ones than can be refilled with liquid, according to a survey by the public-health charity Action on Smoking and Health, based in London. Rechargeable vapes would remain legal.

Global policies

The French government also wants to ban disposable vapes this year, and in December its parliament unanimously backed the proposal. And in 2021, Australia restricted e-cigarette sales to smokers who have a prescription for using vapes to quit smoking. “There is a good consensus that vaping is likely to pose only a small fraction of risks of smoking over the long term,” says psychologist Peter Hajek at Queen Mary University of London, who led a study1 that suggested vaping safely helped pregnant women to stop smoking.

But illegal vaping is still surging among people under the legal age of 18 in Australia, according to research by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. That’s led the government to tighten rules on vape products. “This policy push should see the upswing in youth vaping contained and reversed,” says epidemiologist Tony Blakely at the University of Melbourne in Australia.

The flavoured liquid in vapes also contains solvents such as propylene glycol and glycerin. Agencies including the US and European Union drug regulators have approved these chemicals for oral consumption. But animal studies suggest that inhaling them could cause damage and inflammation, raising the risk of lung and heart disease2. “The issue is we don’t know much about what happens when you heat these products and aerosolize them for inhalation,” says Baglole.

One thing researchers know is that the heating element in e-cigarettes can release heavy metals into the inhaled aerosols. These particles have been linked to a raised risk of heart and respiratory disease, she says.

Ultimately, scientists seem to be overwhelming in favour of tough restrictions on smoking and vaping. Research is needed to establish the long-term health impacts of such policies, says Baglole. “Hopefully different types of studies, different models, in addition to human participants will start to paint a more complete picture,” she says.

[ad_2]

Source Article Link