[ad_1]

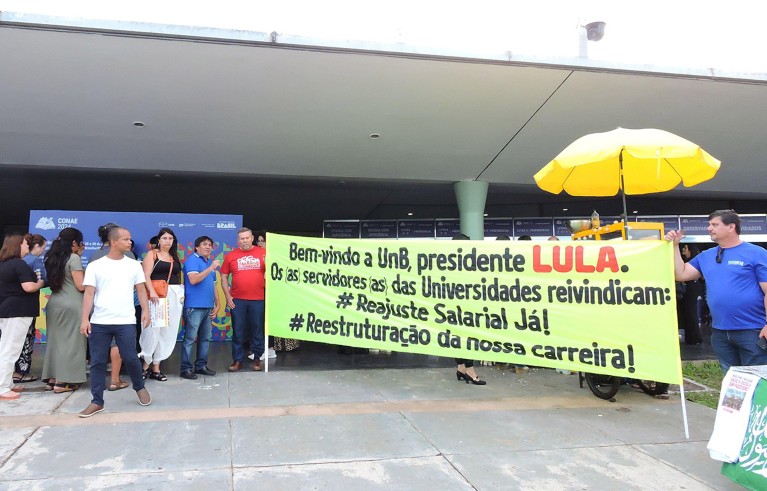

Tensions over university funding in Brazil have been simmering for a while. In January, a Lula administration official visited the University of Brasília and was met by protesters asking for better pay.Credit: Leandro Chemalle/Thenews2/Zuma via Alamy

Academic workers, including many professors, are now on strike at more than 60 federal universities across Brazil. Having faced more than a decade of declining budgets, they are demanding higher wages and more funding to pay for crumbling infrastructure, among other things.

Brazil budget cuts could leave science labs without power and water

Now in their fourth week at some institutions, the strikes have halted classes on many campuses, although scientists contacted by Nature say they are maintaining research laboratories and field projects. The strikes present a major test for President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, a long-time labour leader who entered office last year and promised to boost funding for science and education. The Lula administration has unlocked new financing for research grants and fellowships and is rolling out a new — and controversial — initiative to coax thousands of Brazilian scientists who have moved abroad to return home. Salaries remain flat, however, and base funding for universities has continued to fall, owing in part, some scientists say, to opposition from conservative politicians in the Brazilian Congress.

The question of whether to strike has divided academic workers, as well as students, and many professors have opted to keep teaching, even at institutions where their colleagues have voted to walk out. Many of those striking, meanwhile, hope their actions will give the Lula administration some leverage to negotiate a better deal with lawmakers in Brasília.

“We are not against the government,” says Thiago André, a botanist at the University of Brasília. “We are in negotiation with the government.”

Going down

Public funding for higher education in Brazil has generally been decreasing for more than a decade, with significant cuts enacted under Lula’s conservative predecessor, Jair Bolsonaro. Many academics had hoped that the situation would change under Lula, who expanded investments in the federal university system when he was last Brazil’s president, in 2003–11.

Politics and the environment collide in Brazil: Lula’s first year back in office

Lula has succeeded to some extent in making changes. For instance, his administration has more than doubled the spending from Brazil’s National Fund for the Development of Science and Technology (FNDCT) to 12.8 billion reais (US$2.52 billion) in 2024, says Ricardo Galvão, a physicist who heads the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development, one of the country’s main science agencies. The FNDCT is a core research account in Brazil and is fed by taxes collected from various industries.

Thus far, however, the administration has failed to boost broader funding for universities, including salaries for professors and other staff members.

Since 2014, base funding for federal universities has dropped by around 38%, to an estimated 5.9 billion reais (US$1.16 billion) in 2024, after adjusting for inflation, says Luiz Davidovich, a physicist at the University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and a former president of the Brazilian Academy of Sciences. The result, Davidovich says, is that many universities cannot afford to pay for basic maintenance to keep buildings safe and functional.

For his part, Davidovich joined the majority of professors at his university in voting not to go on strike. “We thought about the students: for them, it would be a disaster” to have their education derailed and graduations delayed, he says. But he sympathizes with those who decided to strike and hopes the situation will raise public awareness and put pressure on the administration and Congress to act.

Galvão acknowledges the challenge ahead. “We need to put much more money in the university system,” he says, but it was perhaps “naive” to expect that the Lula administration would be able to immediately solve the problem.

Continuing talks

It remains unclear how and when the strike might end. One of the the last major strikes by workers at federal universities was in 2015 and lasted around six months. The main union representing professors during the current strike estimates that inflation has reduced the purchasing power of their salaries by around 50% since 2015; union negotiators are asking for a salary increase of nearly 23%. The administration’s latest offer is to boost salaries by 9% in 2025 and another 3.5% in 2026, with no increase this year, according to André.

How is Brazil’s President Lula doing on climate? Experts rate his performance

“It’s not enough,” André says, stressing that professors are not looking for a raise so much as an adjustment for inflation to help them to pay rent and put food on the table. “I think we will stay on strike.”

For botanist Adriana Lobão, the vote to go on strike took place at her institution, Fluminense Federal University in Niteroi, on 29 April. She was conflicted and did not vote, but is now following her colleagues’ decision to strike. Lobão acknowledges that the strike will cause delays in graduation for many students, and others will need to make up for lost time as schedules are readjusted once the strike ends. But she says the situation worsens each year, and thus far most of her students seem supportive of her choice.

“Every day, I hope that the government will make a better offer, so that we can finish this strike,” Lobão says. There’s no end in sight, but she is willing to hold out for now. “I think it’s fair.”

[ad_2]

Source Article Link