[ad_1]

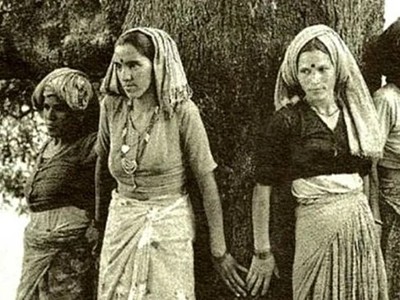

Fifty years ago this week, Gaura Devi, an ordinary woman from a nondescript village in India, hugged a tree, using her body as a shield to stop the tree from being cut down. Little did she know that this simple act of defiance would be a seminal moment in the history of India and the world. Or that Reni village, where she lived, would come to be recognized as the fountainhead of the Chipko environmental movement.

Chipko, in Hindi, means ‘to stick’ or ‘to cling’. In the early 1970s, the Western Himalayan regions of Garhwal and Kumaon, where Reni is situated, were in turmoil. Villagers had been using non-violent methods, including tree hugging, to save their local forests from industrial logging for several months by the time Gaura Devi — and about two dozen women from Reni — showed up on the scene1. But the courage of this small group of women, who stood their ground against loggers who hurled threats and abuses at them, shot the movement to international attention.

What followed holds lessons for a planet teetering on the edge of a climate crisis: marginalized communities can succeed in catapulting environmental concerns into the global spotlight through innovative protest tactics. The Chipko movement gave rise to India’s Forest Conservation Act of 1980, the express aim of which is to conserve woodlands. A few years later, a new federal environment ministry was set up to act as a nodal agency for the protection of biodiversity and to safeguard the country’s environment1–3. Even the origin of the term tree hugger — which has since acquired pejorative connotations — can be traced back to the grassroots ecological consciousness that surfaced in India’s villages.

The origins of India’s environment movement

The movement and its aftermath hold sobering lessons, too. Villagers who threatened to cling on to trees were voicing concern not just about the state of the forests, but also about their own lives and livelihoods. Their desire was to exercise greater local control over woodland resources. Women such as Gaura Devi, for instance, had to walk long distances to gather firewood once the forests were denuded1,4.

Beginning in the late 1960s, activists who took inspiration from the leader of India’s anti-colonial nationalist campaign, Mohandas Gandhi, had begun to mobilize villagers in the Western Himalayas. Their strategy to improve economic opportunity in the region hinged on the Gandhian vision of bottom-up development. A network of cottage industries and cooperatives began to be set up to market forest products. The government’s competing top-down approach of auctioning forests to big private contractors came as an unwelcome intrusion3,5,6.

In essence, what the foot soldiers of Chipko wanted was an acknowledgement of their Indigenous rights to access forest resources that were crucial for their survival. What they got instead was a national law and a ministry populated by a new breed of power brokers — who, in the years to come, would decide at times that habitat preservation is possible only by keeping local communities out.

The big debate

Garhwal and Kumaon, part of the present-day state of Uttarakhand, were at the heart of independent India’s first big debate on environmental justice and equity for a reason. The terrain is mountainous and most of the land is forested. Lives and livelihoods centre heavily around access to land and water resources. Apart from subsistence agriculture, the main source of income in the region 50 years ago was remittance — money sent home from men who had migrated to cities or joined the armed forces2,4,5.

Although daily life was economically precarious for the villagers, the hills also presented them with a fragile environment. In the years preceding the Chipko movement, floods and landslides had wreaked havoc. Some of the villages worst affected lay near forests that had been felled1,5,6.

Three climate policies that the G7 must adopt — for itself and the wider world

The idea of ‘commons’ and ‘sacred forests’ had been an intrinsic part of the cultural ethos of rural India, but the colonial period frayed the bonds that villagers tended to have with their immediate environment. The British Raj’s primary source of income was land revenue. As a result, converting forest or common land into agricultural land by getting rid of existing vegetation was very lucrative1,2.

Things did not improve after independence — the Indian government’s fourth five-year plan (1969–74) directed the state forest departments to take control of forests and open lands. This policy resulted in more restrictions to access for the locals, who depended on nearby woodlands to meet their needs for food, fruit, fodder, firewood and other raw materials2,3.

The spark that ignited Gaura Devi’s tree-hugging protest came when the provincial government handed over ash trees in the Chamoli district of Garhwal to a private contractor to make sports goods. This disregarded the request put forward by a local artisan’s cooperative, the Dashauli Gram Swarajya Sangh (DGSS, Society for Village Self-Rule), which wanted to use the trees to make agricultural implements1,5.

Shade is an essential solution for hotter cities

The manner of protest itself was not new. A year earlier, in March 1973, in the nearby village of Mandal, women and men had come together to prevent the felling of trees under the leadership of a local activist, Chandi Prasad Bhatt, who was associated with the DGSS. As word spread, the act of chipko, or embracing a tree, became an andolan — a movement — which united people across social, caste and age groups, with even children participating in many villages1,5.

However, the protest in Reni village is now recognized as a seminal moment. Gaura Devi was an ordinary woman. But her extraordinary act continues to stand as a prominent signpost in the evolution of India’s ecological consciousness, even 50 years later.

Surprising saviours

On the day the trees near Reni village were to be felled, neither the DGSS members nor the men of the village were present. This was no coincidence, but a deliberate plan by forest department staff, who had organized meetings elsewhere to minimize the possibility of a large-scale protest. However, what they did not account for was the leadership of Gaura Devi, who headed the village’s mahila mandal (women’s group). On being alerted by a young girl who had seen the bus carrying the loggers, Gaura Devi marshalled the women of the village. They put their bodies in front of the axe-wielding men, eventually forcing the loggers to leave1,5.

In Joshimath, India, cracks developed in homes in January 2023 as the town began to sink.Credit: Brijesh Sati/AFP/Getty

What made these village women, whose roles were conventionally restricted to the home, come out in force to protect the trees? The environmental activist Vandana Shiva, adopting an ecofeminist lens, argues that women, especially in rural areas, share close bonds with nature because their daily tasks are entwined with nature7. For the historian Ramachandra Guha, however, although Chipko did see women participating on a scale like never before, it would be simplistic to reduce it to a women’s movement. For Guha, Chipko is a peasant movement centred on the environment, in which both men and women were involved1,5.

Chipko is also synonymous with two men: Bhatt and Sunderlal Bahuguna. Both had strong roots in the community, having worked with voluntary organizations based on the Gandhian ideology of non-violence and satyagraha (which loosely translates as ‘truth force’). Through eco-development camps, Bhatt worked tirelessly to raise awareness about the fragility of the region’s environment. Bahuguna’s padayatras (journeys on foot) across India brought Chipko to the attention of people in other parts of the country and across the world. Chipko thus began to spread3,5,6.

In the forests of the Western Ghats in the south Indian state of Karnataka, Chipko inspired similar protests called Appiko (meaning ‘cling’ in the local language, Kannada). Internationally, Bahuguna took Chipko to university lecture halls in western Europe, and the simple idea of hugging trees for protection also resonated with activists in Canada and the United States6. In 1987, the movement was awarded the Right Livelihood Award, known as the alternative Nobel prize, for its impact on the conservation of natural resources in India.

The afterlife

Over the years, Chipko has been interpreted and reinterpreted by academics and activists. It has been the subject of many books, peer-reviewed papers and popular articles, and is mentioned in the curriculum of Indian schools. Chipko has a prominent place in the discourse on sustainability, too — as an example of the demand for sustainable development at a regional or local level. In March 2018, to commemorate the 45th anniversary of the movement, an iconic photograph of women joining hands around a tree appeared as a Google doodle, highlighting the movement’s international fame.

An immediate effect of the 1974 Reni protest was a 15-year moratorium on tree felling4. A slew of laws and regulations for protecting the forest came into effect. Ironically, Chipko, which had set these laws in motion, resulted in local communities losing access to the very forests that met their livelihood and subsistence needs. Little changed in terms of development or employment opportunities for the locals. With forest protection prioritized, even minor development projects, such as village roads or small irrigation channels, were denied permission. At the same time, large infrastructure projects promoted by the government, such as hydroelectric dams, got the go-ahead2.

The global south is rich in sustainability lessons that students deserve to hear

The fragility of the landscape has steadily worsened. In February 2021, a catastrophic landslide in Chamoli district caused the death of some 200 people. What made the disaster worse were the multiple hydropower plants situated in the path of the landslides. In January 2023, disaster struck again when the town of Joshimath in Chamoli began sinking. Cracks developed on roads and in homes, and people had to be moved to relief camps. The unplanned development of the town on top of an earthquake-induced subsidence zone was a key reason. But a persistent concern in the region is its intrinsic ecological vulnerability, compounded in recent years by climate change.

What is the relevance of Chipko today? According to the United Nations, all of us are living amid the triple planetary crises of climate change, biodiversity collapse and air pollution. Humanity has also transgressed six out of the nine ‘planetary boundaries’ that ensure Earth stays in a safe operating space8. In the context of these monumental concerns, it’s remarkable that Chipko continues to inspire.

Social and environmental movements in India are still guided by its spirit. It is a strategy used by non-governmental organizations, activists and citizen groups in their fight against development projects that adversely affect tree cover. Thus, hundreds of Chipko-like movements have bloomed in villages and cities across India, inspired by a simple idea — hugging a tree to save it — and by the courage of village folk.

A villager from Chamoli, Dhan Singh Rana, wrote a song describing the life and struggles of Gaura Devi, in which he says, “In this world of injustice, show us your miracle again.”3 As the world careens from one crisis to the next, it is more imperative than ever to rekindle the memory of Gaura Devi. It should inspire us to act to save the planet and contribute to sustainable change, putting aside any misgivings about our own limitations as individuals or communities.

[ad_2]

Source Article Link