[ad_1]

Hello Nature readers, would you like to get this Briefing in your inbox free every day? Sign up here.

Previous research has shown that our perception of time is linked to our senses.Credit: Karol Serewis/SOPA Images/LightRocket/Getty

When people look at larger, less cluttered scenes — a big, empty warehouse, for example — they think they viewed it for longer than they actually did. Similarly, people experience time constriction when looking at more constrained, cluttered scenes, such as an image of a well-stocked cupboard. The study of 52 participants also showed that people are more likely to remember the images they thought they viewed for longer. “It suggests that we use time to gather information about the world around us, and when we see something that’s more important, we dilate our sense of time to get more information,” says cognitive neuroscientist and study co-author Martin Wiener.

Reference: Nature Human Behaviour paper

NASA’s interstellar spacecraft has sent updates about its health and operating status after five months of transmitting garbled data. Launched in 1977, Voyager 1 was the first human-made object to leave the solar system. Now 24 billion kilometres from Earth, in November last year it started sending signals that didn’t make sense. Following modifications to how Voyager 1 stores data aimed at fixing the glitch, NASA’s flight team confirmed on 22 April that they were able to communicate with the spacecraft once again. They hope to restore its ability to send back science data, too.

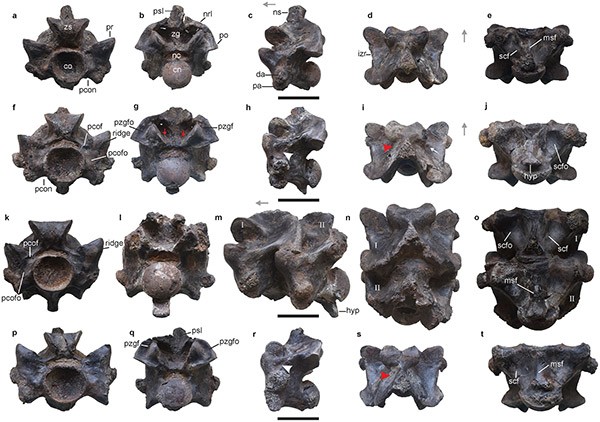

Fossil vertebrae of possibly the longest snake to have ever lived have been unearthed in a coal mine in India. Researchers recovered 27 vertebrae of a snake estimated to reach up to 15 metres in length, more than twice that of the longest snakes alive today, reticulated pythons (Malayopython reticulatus), and probably slightly longer than the extinct Titanoboa. The snake, dubbed Vasuki indicus, lived 47 million years ago.

Reference: Scientific Reports paper

Some of the fossil vertebrae discovered in a mine in Gujarat in western India, the largest of which are about 11 cm wide (Debajit Datta et al/Scientific Reports)

Features & opinion

Tamsin Mather’s book Adventures in Volcanoland takes readers on a journey to some of the world’s most notorious and active volcanoes — and reminds us that the next volcanic catastrophe is inevitable. Yet global preparedness for volcanic eruptions is severely lacking, says fellow volcanologist and reviewer Heather Handley. There is no international treaty organization for volcanic hazards and no global coordination on issuing comprehensive warnings of risks of eruptions, she says. Mather’s book “reminds us that we should all keep careful watch on the world’s volcanoes”.

Researchers urgently need to explore the future carbon footprint of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies, argues a group of sustainability researchers. The direct impacts of AI computing infrastructure — currently about 0.01% of global greenhouse-gas emissions — are likely to remain relatively small, the researchers write. But there could be huge indirect impacts from the way AI tools transform our economies and societies. The group urges researchers to assess whether AI will help or hinder climate progress under different possible scenarios.

“In my flu career, we have not seen a virus that expands its host range quite like this,” says virologist Troy Sutton about H5N1, an avian influenza virus that has rapidly infiltrated species well beyond birds. While most mammal infections were probably caused by contact with an infected bird, there’s evidence that the virus has now evolved to spread directly between some species, such as sea lions. Spreading in more species gives H5N1 opportunities to further adapt to mammals, including humans. So far, the virus doesn’t show signs of being able to cause a pandemic, Sutton says. “If we don’t give it the panic but we give it the respect and due diligence, I believe we can manage it,” adds Rick Bright, chief executive of a public health consultancy.

The New York Times | 10 min read

Where I work

Lindonne Telesford is a public-health researcher, associate lecturer and assistant dean at St. George’s University in Grenada.Credit: Micah B. Rubin for Nature

Public-health researcher Lindonne Telesford explores whether ‘foamed glass’ could help farmers on Grenada to adapt to climate change. The porous material, which is made from recycled glass, is added to soil where it traps and retains water during droughts. In a pilot study, plants grown in soil treated with porous glass had a higher yield than control plants did, Telesford explains. “Agricultural research is a major undertaking for Grenada, because the country has a low research capacity — but every little bit counts if it can bring benefits to farmers and protect our island environment.” (Nature | 3 min read) (Micah B. Rubin for Nature)

A little while ago, I asked readers about their favourite dull lab tasks. You didn’t disappoint: counting worm eggs, restocking pipette tips and hand-grinding fish ears all sound incredibly boring yet strangely satisfying.

“The best job was sterility testing, where one injected media tube after media tube,” recalls retired nurse practitioner Danamaya Gorham. “Nobody would disturb you for about two hours. The loud hiss of the laminar flow obscured the music (and my singing) from the rest of the lab.”

Help to keep this newsletter exciting by sending your feedback to [email protected].

Thanks for reading,

Katrina Krämer, associate editor, Nature Briefing

With contributions by Flora Graham, Smriti Mallapaty and Sarah Tomlin

Want more? Sign up to our other free Nature Briefing newsletters:

• Nature Briefing: Microbiology — the most abundant living entities on our planet — microorganisms — and the role they play in health, the environment and food systems.

• Nature Briefing: Anthropocene — climate change, biodiversity, sustainability and geoengineering

• Nature Briefing: AI & Robotics — 100% written by humans, of course

• Nature Briefing: Cancer — a weekly newsletter written with cancer researchers in mind

• Nature Briefing: Translational Research — covers biotechnology, drug discovery and pharma

[ad_2]

Source Article Link