[ad_1]

Hello Nature readers, would you like to get this Briefing in your inbox free every day? Sign up here.

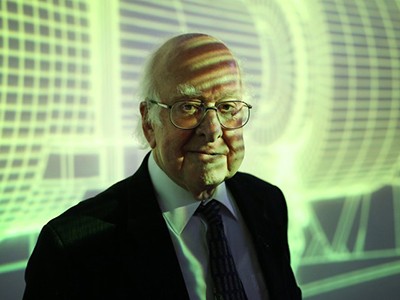

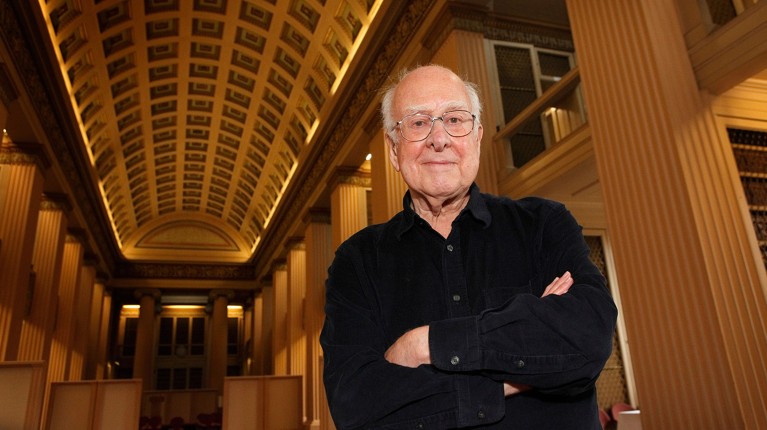

Colleagues remember Peter Higgs as an inspirational scientist, who remained humble despite his fame.Credit: Graham Clark/Alamy

Theoretical physicist Peter Higgs, the namesake of the boson that was discovered in 2012, died on Monday, aged 94. Six decades ago, Higgs first suggested how an elementary particle of unusual properties could pervade the universe in the form of an invisible field, giving other elementary particles their masses. Half a century later, experiments confirmed the prediction and Higgs shared the Nobel prize for the discovery. Notoriously self-deprecating, Higgs was uncomfortable with fame and shunned the spotlight: he was inaccessible by e-mail or mobile phone. “Peter was a very special person, an immensely inspiring figure for physicists around the world, a man of rare modesty, a great teacher and someone who explained physics in a very simple yet profound way,” says Fabiola Gianotti, director-general of CERN.

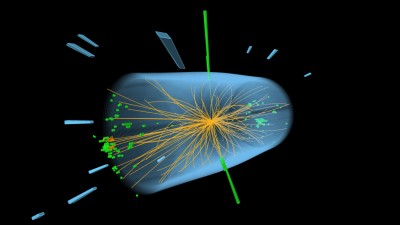

On 4 July 2012, researchers at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider declared success in their long search for the Higgs boson. The elusive particle’s discovery filled in the last gap in the standard model — physicists’ best description of particles and forces — and opened a new window onto physics by providing a way to learn about the Higgs field and how it gives particles their masses. But many of the properties of the Higgs boson remain mysterious.

Nature | 8 min read (from 2022)

In this podcast from 2022, two Nature physics gurus — senior reporter Lizzie Gibney and Federico Levi, a senior physics editor for the journal — looked back to the discovery of the Higgs boson ten years earlier. They reminisce about their experiences of its discovery, what the latest run of the Large Hadron Collider might reveal about the particle’s properties and what role it could have in science beyond the standard model of particle physics.

Nature Podcast | 22 min listen (from 2022)

Subscribe to the Nature Podcast on Apple Podcasts or Spotify.

In a surprise move, Iran has pardoned and released the last four members of a wildlife conservation group that were imprisoned since 2018. The four are part of a group of nine arrested and charged with espionage while carrying out research on Iran’s endangered Asiatic cheetah and Persian leopard. The group’s leader, sociologist Kavous Seyed-Emami, died in prison. The release is “very good news. But nothing can restore the lost years of life and the loss of Emami,” says Kaveh Madani, who was deputy head of Iran’s Department of Environment when he was arrested as part of the same operation.

Avi Wigderson has won what is considered the ‘Nobel Prize’ of computer science for his work on randomness in algorithms. With a series of groundbreaking studies in the 1990s, Wigderson helped to confirm that algorithms that make random choices to achieve their objectives are as accurate as conventional, deterministic algorithms. “I was extremely happy, and I didn’t expect this at all,” Wigderson says. “I’m getting so much love and appreciation from my community that I don’t need prizes.”

In 2019, conservationist Ripi Yanuar Fajar and four others observed what might have been a Javan tiger (Panthera tigris sondaica), which are thought to have gone extinct in the 1980s. Now it seems a strand of hair recovered by researcher Kalih Raksasewu from the location of the sighting 10 days later is a genetic match with a Javan tiger pelt held in a museum. “I wanted to emphasize that this wasn’t just about finding a strand of hair, but an encounter with the Javan tiger in which five people saw it,” says Kalih.

Features & opinion

Artificial intelligence (AI) systems can help researchers to understand how genetic differences affect people’s responses to drugs. Yet most genetic and clinical data comes from the global north, which can put the health of Africans at risk, writes a group of drug-discovery researchers. They suggest that AI models trained on huge amounts of data can be fine-tuned with information specific to African populations — an approach called transfer learning. The important thing is that scientists in Africa lead the way on these efforts, the group says.

Media engagement can open up unexpected opportunities for collaborations and skills development, says physical-activity researcher Ben Singh. Although scientists should court media attention responsibly — the ultimate goal is to inform the public — he suggests pitching published papers to relevant journalists and outlets, writing for websites such as The Conversation or using social media to connect with peers and the public. To avoid overly simplified coverage or misinterpretation of his work, he learnt to “articulate the actual objectives and limitations clearly up front during interviews, conferences and seminars”.

Readers often get in touch about working for Nature, so I wanted to flag a paid opportunity for students and recent graduates in the UK, US and Germany to gain experience in research, education and science news publishing in Springer Nature’s journals, books or magazines. Applicants from all backgrounds are welcome to apply, especially candidates from historically underrepresented groups, including but not limited to Black people, Indigenous people and people of colour, people from socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds, LGBTQ+ people, people from underrepresented social castes, religious minorities and people with a disability and/or a neurodivergent condition. Please find more information on the Springer Nature website.

Among those paying tribute to Peter Higgs, I enjoyed this gem from science-mad comedian Dara Ó Briain: he got Higgs to sign off on a fun joke involving a boson in a jar.

Tonight, I’ll be raising a glass of London Pride, which I’m reliably informed was Higgs’s favourite tipple (and is luckily my favourite beer, too). Tomorrow I hope I return to an inbox filled with your feedback on this newsletter: please e-mail us at [email protected].

Thanks for reading,

Flora Graham, senior editor, Nature Briefing

With contributions by Katrina Krämer

Want more? Sign up to our other free Nature Briefing newsletters:

• Nature Briefing: Anthropocene — climate change, biodiversity, sustainability and geoengineering

• Nature Briefing: AI & Robotics — 100% written by humans, of course

• Nature Briefing: Cancer — a weekly newsletter written with cancer researchers in mind

• Nature Briefing: Translational Research covers biotechnology, drug discovery and pharma

[ad_2]

Source Article Link