[ad_1]

Hello Nature readers, would you like to get this Briefing in your inbox free every day? Sign up here.

Credit: incamerastock/Alamy

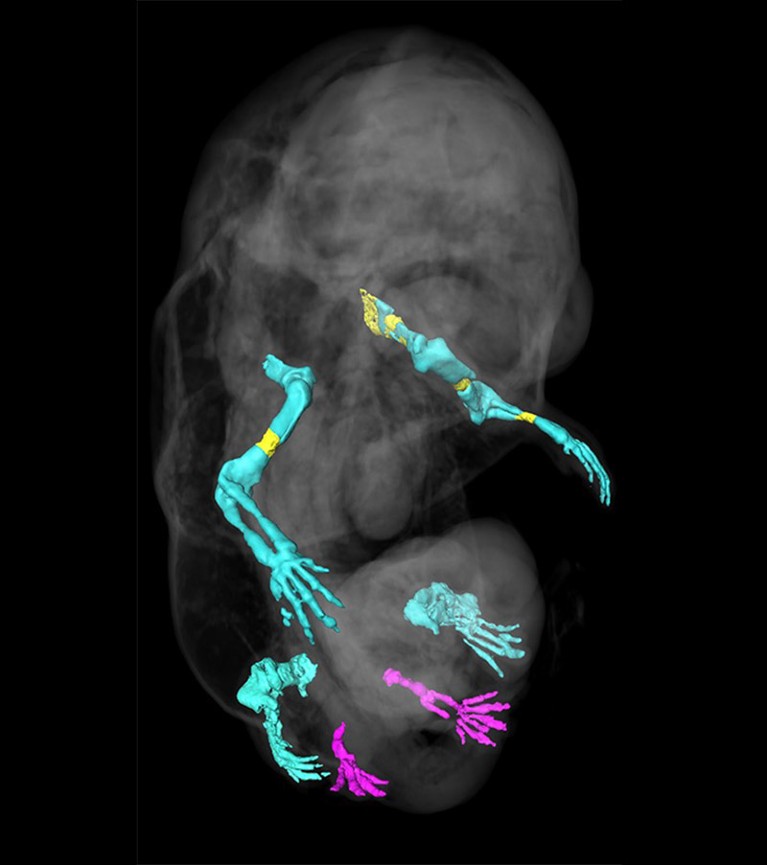

Left-handed people are almost three times more likely to have rare variants in the genes for tubulins, proteins that build cells’ internal skeletons. Tubulins assemble into long filaments called microtubules, which control the shapes and movements of cells. Microtubules could influence handedness because they form hair-like protrusions in cell membranes that can direct fluid flows in an asymmetric way during embryonic development.

Reference: Nature Communications paper

Super-Earth LHS 3844b is the first exoplanet to show convincing signs of tidal synchronization, meaning one of its hemispheres is permanently illuminated by its star and the other is in permanent darkness. The planet is relatively cool, indicating that it lacks the tidal heating non-locked planets experience. It’s unclear whether tidally locked planets could be habitable. These worlds “don’t have tides, or seasons or day–night cycles”, says astronomer and study co-author Nicolas Cowan. “Could you get the same kind of diversity and complexity of life evolving? I have no idea.”

Reference: The Astrophysical Journal paper

Biotechnology company LyGenesis has injected donor liver cells into a lymph node of a person with liver failure for the first time. The idea is that, within months, the donor cells will grow into a blood-filtering ‘miniature liver’. “It’s a very bold and incredibly innovative idea,” says liver-regeneration specialist Valerie Gouon-Evans. The treatment, which has been trialled in mice, dogs and pigs, might not relieve all of the complications of end-stage liver disease — but could provide a stopgap until a donor organ becomes available or make people healthy enough to undergo a transplant.

Nearly 20% of almost 600 image-containing papers that scientists compiled for a systematic review had suspicious images, including those that had been duplicated, stretched or rotated. Out of the 132 studies the researchers included in their final review, which was about a test to identify depression-related symptoms in rats, 10 contained potentially doctored images. Analysing these 10 alone assessed the test as 50% more effective than did the remaining 122 studies. This “clearly highlights [that falsified images] are impacting our consolidated knowledge base”, says systematic-review methodologist Alexandra Bannach-Brown.

Reference: bioRxiv preprint (not peer reviewed)

Features & opinion

When microbes’ ability to develop is pitted against their ability to make pharmaceuticals or biofuels, “the cells are going to choose to grow every time”, says synthetic biologist Brian Pfleger. To sidestep this unwinnable metabolic-resource war, researchers are introducing new biosynthesis pathways that can run alongside natural processes. For this, they have zeroed in on cofactors, small molecules that help enzymes do their work. Eventually, synthetic cofactors paired with the enzymes that use them could allow cells to churn out compounds more efficiently or even make those that rarely occur in nature.

With Twitter on the wane among many scientists — both as a place to post and a source of social-media data — some are turning to Reddit. Access to Reddit data is free for non-commercial researchers and academics. And its communities offer a space to network and chat, with an ‘upvote and downvote’ system helping good content rise to the top. Nature offers some context and advice for those looking to take the plunge.

Cancer cells make proteins found nowhere else in the body. Vaccines could teach the body’s immune system to recognise these proteins and destroy the cancer cells. The most powerful vaccines are created from the specific proteins extracted from a patient’s tumour and, in some cases, use the patient’s own immune cells. Researchers are also working on doing this vaccination process entirely within the body: first, drugs activate the immune system, then radiotherapy kills cancer cells, releasing the cancer proteins for the switched-on immune cells to find.

This article is part of Nature Outline: Cancer vaccines, an editorially independent supplement produced with the financial support from Moderna.

Where I work

Muh Aris Marfai is head of the Geospatial Information Agency of Indonesia in Bogor and a geography researcher at the Gadjah Mada University in Yogyakarta.Credit: Gaia Squarci for Nature

Geographer Muh Aris Marfai collects reference data for Indonesia’s coastal areas to prepare for the impacts of climate change. “Because so much of the country is surrounded by water, it’s important to pay attention to coastal areas,” he says. “Many coastal cities, including Jakarta, are experiencing subsidence owing to geological processes and coastal dynamics.” (Nature | 3 min read)

Today I’m enjoying the fish doorbell — a charming solution to alert the lock keepers of Utrech’s boat canal to let through migrating fish. A webcam allows watchers to ‘ring the doorbell’ for the fish, sending a photo to ecologists who signal that it’s time to clear the underwater traffic jam. The doorbell has struck a chord with nature-lovers, meaning the 950-ish slots for aspiring doorbell-ringers are often full. And even if you do get access, you might wait days to spot a fish in the murky waters. But all the enthusiasm is good news for ecologist Mark van Heukelum, who created the gadget. “We ‘only’ get a thousand pictures of every fish that appears for the camera,” he jokes on the fish-doorbell website.

Thanks for reading,

Flora Graham, senior editor, Nature Briefing

With contributions by Katrina Krämer

Want more? Sign up to our other free Nature Briefing newsletters:

• Nature Briefing: Anthropocene — climate change, biodiversity, sustainability and geoengineering

• Nature Briefing: AI & Robotics — 100% written by humans, of course

• Nature Briefing: Cancer — a weekly newsletter written with cancer researchers in mind

• Nature Briefing: Translational Research covers biotechnology, drug discovery and pharma

[ad_2]

Source Article Link