[ad_1]

Dairy cattle seem to survive infection with the H5N1 strain of influenza virus, which has killed millions of wild birds.Credit: Ben Brewer/Reuters

Concerns that pasteurized milk in the United States is teeming with H5N1 avian influenza virus are over. But there’s no sign that the outbreak in cows is over, and scientists are increasingly concerned that cattle will become a permanent reservoir for this adaptable virus — giving it more chances to mutate and jump to humans.

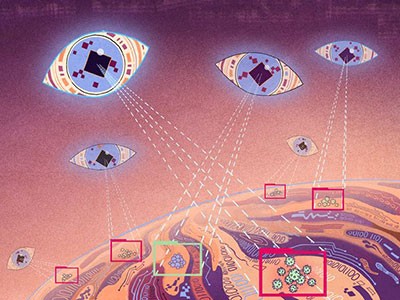

New data show that the virus can hop back and forth between cows and birds, a trait that could allow it to spread across wide geographical regions. Although the virus kills many types of mammal, most infected cows don’t develop severe symptoms or die1, meaning that no one knows whether an animal is infected without testing it. Moreover, a single cow can host several types of flu virus, which could, over time, swap genetic material to generate a strain that can more readily infect humans.

“Eventually the wrong combination of gene segments and mutations inevitably comes along,” says Michael Worobey, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Arizona in Tucson. “Whatever opportunity we may have had to nip it in the bud we lost by a really slow detection.”

Viral expansion

H5N1 isn’t a new virus — various forms of it have been circulating since the 1990s. A particularly deadly variant that was first detected in 1996 has killed millions of birds and has been found in numerous mammalian species, including seals and mink. But until now, cows were not among the virus’s known hosts.

US officials first announced on 25 March that H5N1 had been found in cattle, and cows from 36 herds in 9 states have tested positive as of 7 May. Tests of pasteurized milk have found no living virus. But the virus’s increasing ubiquity has made scientists uneasy.

“Every time it gets a new mammalian host species like cows, there’s more risk of human transmission and reduced human immunity,” says Jessica Leibler, an environmental epidemiologist at Boston University in Massachusetts.

Bovine breakthrough

Genomic data are starting to shed light on the origins of the cattle outbreak. In a 1 May preprint2 posted on bioRxiv, scientists at the US Department of Agriculture analysed more than 200 viral genomes taken from cows and found that the virus jumped from wild birds to cattle in late 2023. That result corroborates findings by Worobey and others in an analysis posted on the discussion forum virological.org on 3 May. (Neither article has yet been peer reviewed.)

Want to prevent pandemics? Stop spillovers

Because cows infected with H5N1 generally don’t die of the flu, they are “effective mixing vessels” in which viruses can swap genetic material with other viruses, says Angela Rasmussen, a virologist at the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon, Canada. Even worse, the current strain seems to infect several species equally well. “If you have a virus that’s hopscotching back and forth between cows, humans and birds, that virus is going to have selective pressures to grow efficiently in all those species,” she says.

The larger the number of infected animals, Rasmussen says, the more chances the virus has to acquire helpful mutations, such as the ability to grow in the upper respiratory tract, which could make it more transmissible between people.

Dangerous reservoir

From a human perspective, Worobey says, cows might be one of the worst possible animal reservoirs for influenza because of their sheer number and the degree to which humans interact with them. Culling poultry has curbed previous bird flu outbreaks, but Rasmussen says that isn’t a viable option for cattle. The animals are too valuable and, unlike birds, don’t seem to die from the infection.

H5N1 could even become endemic in cows, says Gregory Gray, an infectious-disease epidemiologist at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. Other strains related to H5N1 are already endemic in chickens and pigs in some parts of the world.

Flu on the farm

Researchers aren’t sure how the virus is spreading between herds. Wild birds, which congregate around cattle feed and defecate in the cows’ water supply, are one probable source. “Cattle are just one big birdfeeder,” Gray says, adding that birds can spread infections much further than cows can and are much less controllable.

Some evidence has suggested that farm equipment, such as milking machines, could be to blame, but several scientists worry that it could be airborne. “I’m really thinking that’s occurring and we’ve not been able to study it,” Gray says, mainly because farmers have been reluctant to allow inspectors to test their cattle. Some related variants that infect horses have been found to spread through the air for kilometres, which could explain how the current strain has moved between dairy farms.

Until more is known about the virus’s transmission route, Worobey says, it’s hard to determine the best way to contain it. Since late April, the US Department of Agriculture has required that cows are tested before being transported across state lines. That won’t necessarily stop the virus’s spread, but it could at least help researchers to understand where it’s going.

Herd immunity

If the virus is airborne, Gray says, vaccinating cows might be an option. H5N1 vaccines have not yet been used in US cattle. But influenza vaccines have proved effective in pigs and poultry, and researchers are beginning to test them against the H5N1 strain infecting dairy herds.

Data on how well the virus spreads between people are scarce. A study3 published on 3 May in the New England Journal of Medicine confirmed that one dairy worker in Texas had been infected and that the worker experienced mild symptoms. But the people who worked and live with the infected person have not been tested.

Still, US officials have not reported a large number of deaths or severe cases in humans, suggesting that the virus hasn’t become highly transmissible or deadly, Worobey says.

Below the radar

But Gray says that there have been anecdotal reports of many more human cases. Leibler suspects that exposure of farm workers is widespread. “When you see symptomatic patients, that’s the tip of the iceberg,” she says. In the worst-case scenario, she says, the virus would spread undetected in several species for a long time, accumulating mutations that prime it for causing a pandemic in the future. “We have an awareness now from the COVID pandemic of how devastating that could be,” she says.

Leibler hopes that public-health efforts will begin testing workers and their families so that any transmission in humans will quickly be detected. “H5N1 is with us,” she says. “It’s not a virus that’s going to disappear by any means.”

[ad_2]

Source Article Link