[ad_1]

Hello Nature readers, would you like to get this Briefing in your inbox free every day? Sign up here.

The field of audiomics combines artificial intelligence tools with human sounds, such as a coughs, to evaluate health.Credit: Getty

A machine-learning tool shows promise for detecting COVID-19 and tuberculosis from a person’s cough. While previous tools used medically annotated data, this model was trained on more than 300 million clips of coughing, breathing and throat clearing from YouTube videos. Although it’s too early to tell whether this will become a commercial product, “there’s an immense potential not only for diagnosis, but also for screening” and monitoring, says laryngologist Yael Bensoussan.

Reference: arXiv preprint (not peer reviewed)

Everyone knows that usually, when it comes to charged particles, opposites attract. But in liquids, birds of a feather can flock together. Researchers investigating the long-standing mystery of why like-charged particles in solution can be drawn to each other have found that the nature of the solvent is key. The way that the liquid molecules arrange themselves around the particles can generate enough ‘electrosolvation force’ to overcome electromagnetic repulsion. The findings might require “a major re-calibration of basic principles that we believe govern the interaction of molecules and particles, and that we encounter at an early stage in our schooling,” says physical chemist and co-author Madhavi Krishnan.

Reference: Nature Nanotechnology paper

A study of 34 years of online discussions from Usenet to YouTube shows that, when it comes to rude behaviour, people — not platforms — are the root of incivility. Researchers used Google’s artificial-intelligence (AI) ‘toxicity classifier’ to identify “rude, disrespectful or unreasonable” comments. They found that over three decades, longer discussions tend to be more toxic, but heated debates don’t necessarily escalate or drive away participants. “Despite changes in social media and social norms over time, certain human behaviours persist, including toxicity,” says data scientist and co-author Walter Quattrociocchi.

Reader poll

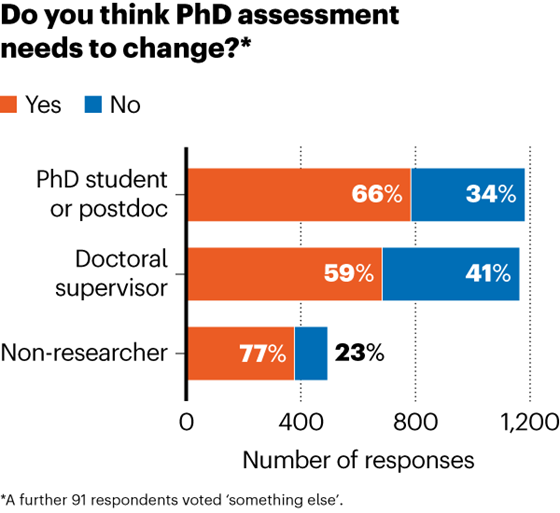

Last week, a Nature editorial argued that the way PhDs are assessed needs to change. Briefing readers largely agree.

“I acknowledge granting a PhD is a messy business — there is no fixed bar that candidates have to meet to successfully defend,” says recently minted physics PhD Kai Shinbrough. He says that more transparency around the process would go a long way to alleviate candidates’ anxieties.

Readers’ suggestions included assessing dissertations in a similar way to grant proposals — in writing, with iterative feedback cycles — or opening theses to public comments. Many felt there should be more emphasis on evaluating PhD projects on their originality, methods and analysis rather than their ‘positive’ or ‘negative’ outcomes.

Others highlighted that assessment shouldn’t be generalized across all academic disciplines with their varying contexts, cultures and histories. “Breathless demands for sweeping innovation in yet another domain of higher education would certainly lead to additional demands on the time and workloads of supervisors” and further disincentivize PhD supervision, says linguist Mark Post.

Several readers felt that their supervisors’ hands-off leadership left them to mostly fend for themselves and missing out on learning important skills, such as grant writing or lab management. “Research should not be a painful or solitary endeavour, it should be a communal effort driven by individuals committed to serving society,” says linguist Izadora Silva Pimenta.

Features & opinion

A massive mouse-embryo map tracks the development of more than 12 million cells as they mature into organs and other tissues. Building these cell atlases typically requires multinational collaborations and lots of cash. But this one was completed in one year by a three-researcher team on a US$370,000 budget. Among the first insights from the data is that the transcriptome (the cells’ set of messenger RNA) changes most dramatically in the hour just after birth: it’s “the most stressful moment in your life”, says geneticist and atlas co-creator Jay Shendure.

A casualty of faster-than-light travel and a teenage remnant of Homo sapiens grapple over whether it was all worth it in the latest short story for Nature’s Futures series.

Song differences too subtle for people to hear are the special spice that make some male zebra finches (Taeniopygia guttata) particularly attractive to females. Researchers used an AI algorithm to analyse various acoustic features and create maps of the songs’ syllables. Female finches preferred songs with wider statistical gaps on these maps — they seem to be harder to learn and therefore indicate the singer’s fitness. How this statistical distance translates into sonic quality isn’t clear yet. “They all sounded like just a regular learned zebra finch on to our ear,” says neuroscientist and study co-author Todd Roberts.

Nature Podcast | 30 min listen

Subscribe to the Nature Podcast on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts or Spotify, or use the RSS feed.

[ad_2]

Source Article Link