[ad_1]

Hello Nature readers, would you like to get this Briefing in your inbox free every week? Sign up here.

A woman plays Go with an AI-powered robot developed by the firm SenseTime, based in Hong Kong.Credit: Joan Cros/NurPhoto via Getty

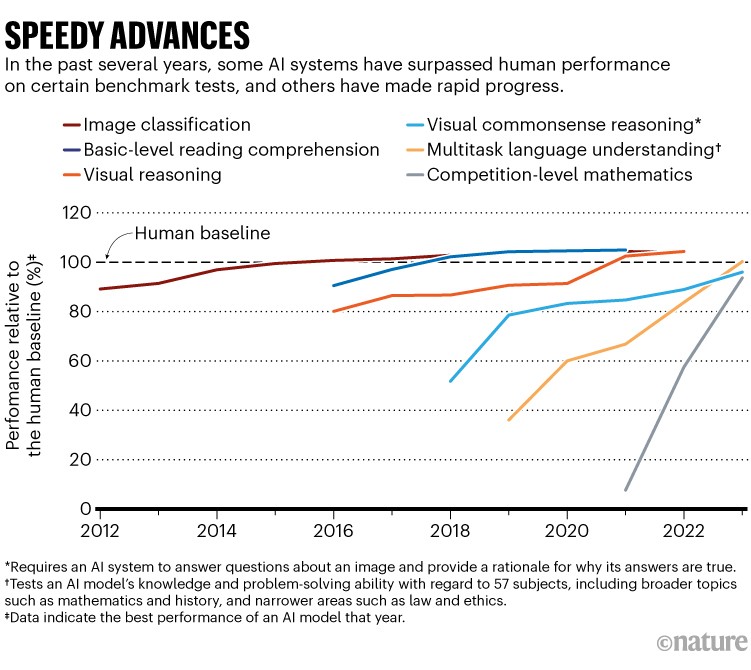

AI systems can now nearly match (and sometimes exceed) human performance in tasks such as reading comprehension, image classification and mathematics. “The pace of gain has been startlingly rapid,” says social scientist Nestor Maslej, editor-in-chief of the annual AI Index. The report calls for new benchmarks to assess algorithms’ capabilities and highlights the need for a consensus on what ethical AI models would look like. The report also finds that much of the cutting-edge work is being done in industry: companies produced 51 notable AI systems in 2023, with 15 coming from academic research.

Reference: 2024 AI Index report

An experimental AI system called the Dust Watcher can predict the timing and severity of an incoming dust storm up to 12 hours in advance. Harmful and damaging dust storms — like the ones that battered Beijing over the weekend — sweep many Asian countries every year. A separate storm predictor, called Dust Assimilation and Prediction System, dynamically integrates observational data with the calculations of its model to generate a 48-hour forecast. “It almost acts like an autopilot for the model,” says atmospheric scientist Jin Jianbing.

A study identified buzzwords that could be considered typical of AI-generated text in up to 17% of peer-review reports for papers submitted to four conferences. The buzzwords include adjectives such as ‘commendable’ and ‘versatile’ that seem to be disproportionately used by chatbots. It’s unclear whether researchers used the tools to construct their reviews from scratch or just to edit and improve written drafts. “It seems like when people have a lack of time, they tend to use ChatGPT,” says study co-author and computer scientist Weixin Liang.

Reference: arXiv preprint (not peer reviewed)

An AI model learnt how to influence human gaming partners by watching people play a collaborative video game based on a 2D virtual kitchen. The algorithm was incentivised to gain points by following certain rules that weren’t known to the human collaborator. To get the person to play in a way that would maximize points, the system would, for example, repeatedly block their path. “This type of approach could be helpful in supporting people to reach their goals when they don’t know the best way to do this,” says computer scientist Emma Brunskill. At the same time, people would need to be able to decide what types of influences they are OK with, says computer scientist Micah Carroll.

Reference: NeurIPS Proceedings paper

Image of the week

NASA/JPL-Caltech

This snake robot, photographed here during tests on a Canadian glacier, could one day explore the icy surface and hydrothermal vents of Saturn’s moon Enceladus. Spiral segments propel the more than four-metre-long Exobiology Extant Life Surveyor (EELS) forward while sensors in its ‘head’ capture information. “There are dozens of textbooks about how to design a four-wheel vehicle, but there is no textbook about how to design an autonomous snake robot to boldly go where no robot has gone before,” says roboticist and EELS co-creator Hiro Ono. “We have to write our own.” (Astronomy | 4 min read)

Reference: Science Robotics paper

Features & opinion

AI systems can help researchers to understand how genetic differences affect people’s responses to drugs. Yet most genetic and clinical data comes from the global north, which can put the health of Africans at risk, writes a group of drug-discovery researchers. They suggest that AI models trained on huge amounts of data can be fine-tuned with information specific to African populations — an approach called transfer learning. The important thing is that scientists in Africa lead the way on these efforts, the group says.

Malicious deepfakes aren’t the only thing we should be concerned about when it comes to content that can affect the integrity of elections, says US Science Envoy for AI Rumman Chowdhury. Political candidates are increasingly using ‘softfakes’ to boost their campaigns — obviously AI-generated video, audio, images or articles that aim to whitewash a candidate’s reputation and make them more likeable. Social media companies and media outlets need to have clear policies on softfakes, Chowdhury says, and election regulators should take a close look.

AI models trained on a deceased person’s emails, text messages or voice recordings can let people chat with a simulation of their lost loved ones. “But we’re missing evidence that this technology actually helps the bereaved cope with loss,” says cognitive scientist Tim Reinboth. One small study showed that people used griefbots as a short-term tool to overcome the initial emotional upheaval. Some researchers who study grief worry that an AI illusion could make it harder for mourners to accept the loss. Even if these systems turn out to do more harm than good, there is little regulatory oversight to shut them down.

Reference: CHI Proceedings paper

[ad_2]

Source Article Link