[ad_1]

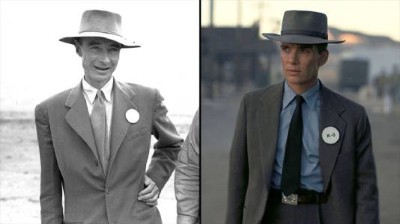

Cillian Murphy picked up the best actor award for his portrayal of Oppenheimer.Credit: Landmark Media/Alamy

Oppenheimer won big at last night’s Oscars, scooping 7 awards out of 13 nominations, including best picture. The film has been lauded for its accurate portrayal of physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer’s life, and its examination of both the human and scientific toll of the Manhattan Project, the research programme that developed the atomic bomb in the 1940s at Los Alamos in New Mexico.

To ensure the film was as accurate as possible, director Christopher Nolan turned to several science advisers for information on Oppenheimer and his life, and the project itself, which culminated in the Trinity Bomb nuclear test on 16 July 1945 and the subsequent bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan, bringing the Second World War to a close at immense human cost.

Nature spoke to three of those advisers for some behind-the-scenes insight into the film’s creation.

Why Oppenheimer has important lessons for scientists today

Robbert Dijkgraaf, a theoretical physicist and currently the Dutch minister for education, was the director of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, from 2012 to 2022, a job Oppenheimer had also held, from 1947 to 1966. Kip Thorne, a theoretical physicist at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, is a close friend of Nolan’s and had worked with him on a number of previous projects, including the depiction of the gargantuan black hole in the film Interstellar (2014). And David Saltzberg, a physicist at the University of California, Los Angeles, worked as a scientific consultant for other productions, such as The Big Bang Theory, before applying his expertise to Oppenheimer.

What was your involvement in Oppenheimer?

Dijkgraaf: In 2021, Nolan wanted to come and visit, to see the place where Oppenheimer had lived and worked for almost 20 years. I also lived in that house and, for 10 years, worked in the same office that Oppenheimer once used. We had a long discussion about Oppenheimer, but also about physics, which I loved.

Thorne: I spoke with Cillian Murphy about his portrayal of Oppenheimer for the movie. I knew Oppenheimer when I was a graduate student at Princeton, from 1962 to 1965, and a postdoc from 1965 to 1966, so there was some discussion about Oppenheimer as a person.

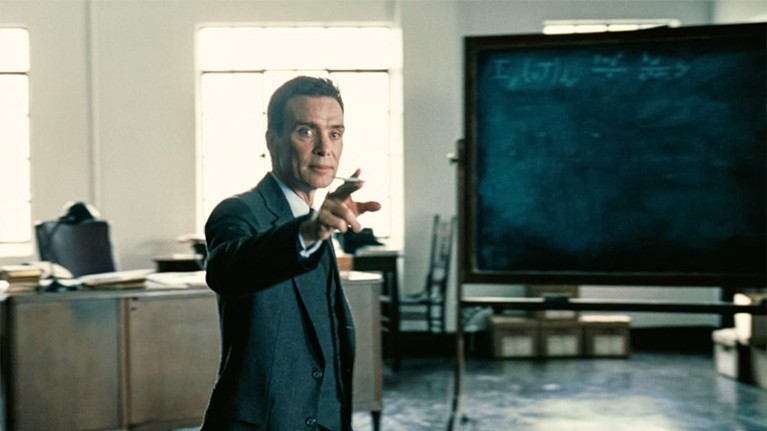

Saltzberg: I was called in to help out with the production in scenes that were filmed in Los Angeles. I worked mostly with the prop manager. That involved things like deciding what was on the chalkboards, or what equations Oppenheimer handed to Einstein to show whether the atmosphere would catch fire.

Tell us about some of your interactions with the director and cast

Dijkgraaf: Nolan visited Princeton twice to tour the premises. I remember we walked from the house to the institute. It’s this beautiful walk with nice trees. I remember telling him it’s the perfect commute, because Einstein and [Austrian physicist] Kurt Gödel always walked along that path. In the movie, Lewis Strauss meets Oppenheimer and he points out the house and says “it’s the perfect commute”. I thought, ‘wait a moment — this is a very familiar scene!’

I was struck that Nolan was really, really interested in what it means to be a physicist.

I also remember he really appreciated the pond at the institute. Quite a few of the scenes in the movie are shot near the pond — it’s a favourite place for many people there. It’s a place to think and contemplate.

Saltzberg: I sometimes had to explain the physics of a line of dialogue to the actors, enough that they knew the emotional truth of the line and why they were saying it. There was one particular line in the script which was incredibly complicated, about off-diagonal matrix elements and quantum mechanics. Even when I read it I had trouble understanding exactly what it was saying. Cillian really wanted me to explain it to him. We got there, I think, but it was difficult.

A similar thing happened with Josh Hartnett, who played [American nuclear physicist] Ernest Lawrence. Every time he had a spare moment, he would come and talk to me about physics. It was uncanny because he was already in makeup and costume. I never met Lawrence, but I’ve seen plenty of pictures, and it was just eerie. He looked like Lawrence walking around the room.

What did you make of the science in the movie?

Saltzberg: It was wonderfully accurate. It’s really amazing. Christopher Nolan clearly understood the science.

There’s a scene in which Oppenheimer is writing on the chalkboard explaining that nuclear fission is impossible, when Lawrence walks in and says “well, [American physicist Luis Walter] Alvarez just did it next door”. So I had some equations put on the board that Oppenheimer might have had that proved fission is impossible. Most of the audience wouldn’t recognize that, but it made me feel good.

Dijkgraaf: It was really well done. I loved that the movie consistently looks through the eyes of Oppenheimer. The physics discussions were very good — the right equations were on the blackboards!

What was Oppenheimer like as a person?

Thorne: He was just a superb mentor, extremely effective. He had enormous breadth and an extremely quick mind. He had this amazing ability to grasp things very quickly and see connections, which was a major factor in his success as the leader of the atomic bomb project.

Dijkgraaf: He was both a scientific leader and a government adviser. At that time, Einstein, who was quite crucial in starting up the atomic bomb project, really turned into a father of the peace movement. A character who wasn’t in the movie, [Hungarian-American mathematician] John von Neumann, wanted to bomb the Soviet Union, so he was completely on the opposite side. Oppenheimer was trying to walk the reasonable path between those two extremes, and he was punished for it. So I often feel his character generates these mixed feelings. It’s a fascinating example for anyone who wants to be a scientist and play a role in public debate.

Is it satisfying to see a science-based film get such recognition at the Oscars?

Thorne: It’s wonderful it’s got this level of attention. It’s a film that has messages that are tremendously important for the era we’re in. Hopefully it raises the awareness of the danger of nuclear weapons and the crucial issue of arms control.

Dijkgraaf: We often complain there’s no content in popular culture. For me, the biggest surprise was that this difficult movie about a difficult topic and a difficult man, shot in a difficult way, became a hit around the world. I feel that’s very encouraging. The hidden life of physicists has become a part of popular culture, and rightly so.

[ad_2]

Source Article Link