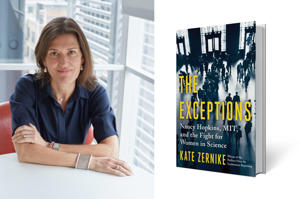

© Harry Zernick; Scribner author Kate Zernick and her book Exceptions.

© Harry Zernick; Scribner author Kate Zernick and her book Exceptions.

Nancy Hopkins and 15 MIT colleagues teamed up in the 1990s to show gender differences among teachers. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology agreed, and these changes helped bring about a sea change for women in all academic and research settings. How did this happen? Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Keith Zernick tells his story in his new book, Exceptions (Scribner, February). In this Q&A, she talks about the achievements she's helped create, the challenges women in STEM still face, and what's key to ensuring equal opportunities for girls and women in science.

Question: Why are you writing this book? why now

A: I started thinking about writing this book in January 2018, just as the #MeToo movement was starting to grow. These dire circumstances got me thinking about the kind of discrimination women were talking about at MIT in 1999: the hidden ways women are marginalized in the workplace, especially as they get older. I think it's more common and subtle. One of the key points the women at MIT made was that opening doors for women is not enough, you have to make sure you value them and treat them as equals in their careers. What struck me was that the challenges women face in science highlighted a larger problem, which is that we still don't take women seriously in intellectual and professional circles. This story is even more relevant now that the country is once again debating whether we need affirmative action. These women believed that there would be pure meritocracy with an emphasis on scientific data and facts. You discover that there is no such thing.

The efforts of Nancy Hopkins and her colleagues led to advances in academic scholarship. Has it influenced other science fields and STEM careers?

When the MIT report was published, MIT had never had a department head. Today, women lead the university, from the board of trustees to the president and dean of science. (Like the states of Massachusetts and the city of Boston). Back then, the Ivy League had only one female president, and this fall, six of those eight organizations are led by women. This is a small elite segment, but these universities are good at spotting trends. There are other subtle changes: when MIT women first began to address the issue, no female professors took maternity leave because of stigma. Professors at many universities now say that they are no longer the exception when colleagues send their children to day-care centers that didn't exist in 1999. Universities usually stop teaching when women (and men) have children. The President of the National Academy of Sciences and three of President Biden's top science advisers are all women, as are the people leading vaccine development as the world battles the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet very few women win the Nobel Prize in Science, reminding us that we still have a long way to go in terms of education and women's contribution.

Given the pay gap between women and men in STEM positions, how important is the MIT Group? What comes after the fight?

In most regions, women are still paid less than men for the same work. There is nothing a group of women at a university can do about that, it all depends on the men and women who run companies and universities. The women at MIT had no idea the report would be read off campus. But the excitement surrounding her story prompted other universities to run similar tests. It also prompted the National Science Foundation to create a program aimed at eliminating inequalities in teaching approaches, grant awarding, and propensity for employment.

The number of women entering science and technology colleges is still disproportionately high. A 2018 report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine found that nearly half of the women at these colleges have been sexually abused. A small percentage of these disorders are linked to sexual assault. By far the biggest problem was what the report called "gender harassment" by women at MIT. These are sexual slurs against women in science, rude comments that make women feel unwelcome in this environment. This is especially true for doubly marginalized women: women of color, lesbians, or women we traditionally see as masculine in appearance or behavior.

When Larry Summers, then-president of Harvard University, commented on women's "internal problems," it sparked another storm of controversy on the subject. How many people still think women's progress in this area is "extraordinary"?

I followed this story closely in 2005, but when I came back I was shocked to see a spate of articles defending Larry Summers, despite much research to refute his claims. Some of her ideas – not only that women lack inner strength, but also that they don't want to work 80 hours a week – have been around since the beginning of the last century. I think there is a lot of awareness now. “Exclusions” also points out how these women articulate subtle forms of discrimination; They assumed it was due to circumstances or blamed themselves. I think we now have a better understanding of systemic bias.

Nancy's report was never published. Why? Do you think the information there can help current and future women who want to break the glass ceiling?

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology has not released the full report because it contains stories by or about professors that are subject to confidentiality. You cannot anonymize these stories. Even the word "junior math teacher" would indicate a woman, for there were one or two of them. The stories are in the book and I think they illustrate the assumptions and patterns women still have to work with and the pitfalls to avoid.

What was the most surprising thing you learned from reading this book?

That shouldn't surprise me and us, but we were reminded of how long we've been talking about the same problems, even finding solutions, but doing nothing. President Kennedy's Women's Commission recommended paid maternity leave in 1963; It took decades to get it. Research conducted in the 1970s showed that we all, men and women, valued the same CV less if it had a woman's name on it rather than a man's. It's a reminder that every generation thinks it has solved a problem, but every generation reinvents it.

What is the key to ensuring equal opportunities for girls and women in science?

Changing attitudes is key when it comes to hiring institutions and talking about who does the most important work in science. Who comes to mind when we hear the word "genius" – research shows that it's mostly men. MIT's School of Engineering made strides toward hiring more women after the report, as a male dean refused to chair re-education committees, as he often does, saying women were not eligible for the appointment. He said look again.

Related Articles

Start an unlimited Newsweek trial