Standing on the podium in the Astrodome in Houston, Pat Buchanan frowned as he painted a picture of America's greatest enemy of the post-Cold War era: the enemy within.

“My friends, this election is not just about who gets what. It's about who we are. It's about what we believe in as Americans and what we stand for," Buchanan said. “There is a religious war going on in this country. This is a culture war that is as important to the kind of nation we are becoming as the Cold War itself, because that war is at the heart of America.”

Learn more about Houston in the 90's

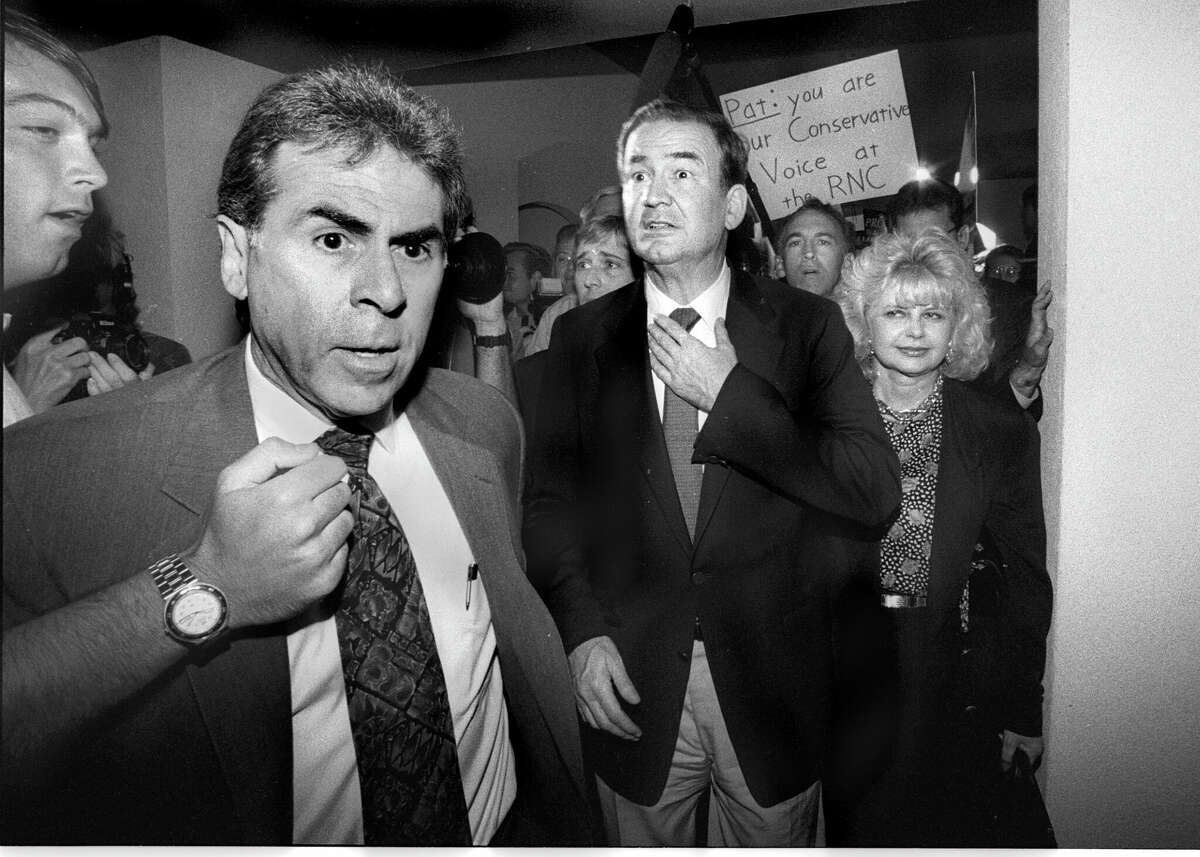

Buchanan's remarks, made during the first keynote address at the 1992 Republican National Convention in Houston, ushered in a new era in American politics, one of blame, resentment and the demonization of secular society.

GOP members, gathered in Houston's ultra-modern vaulted building, listened as Buchanan urged conservative Americans to rhetorically take up arms against those who threaten their traditional values, comparing the social struggle ahead to that of the armed forces. . US soldiers push back a crowd during the 1992 Los Angeles riots.

"As these kids reclaim the streets of Los Angeles block by block, my friends, we must reclaim our cities, reclaim our culture, and reclaim our country," Buchanan said.

In the three decades since Buchanan popularized the phrase, "culture war" has evolved from a tactic of the far right to an organizing principle at the heart of American conservatism. The language of the culture war is so ingrained in American discourse that it has become ubiquitous: terms like “radical,” “establishment,” and “political correctness” have become common sense and have been used as catchphrases. Pages. In 2020, President Donald Trump cited the culture war as the number one reason Republicans should unite in their campaigns against Democratic opponents.

This is a carousel. Use the Next and Previous buttons to navigate

"We're in a culture war," Trump told RealClear Politics amid his failed 2020 presidential reelection campaign.

Challenging the status quo

The main components of the Kulturkampf are the presence of foreigners: immigrants, minorities and the poor; marginalized groups that can be singled out as the source of the nation's economic problems. Decades before Trump pushed for a wall on the US-Mexico border, Buchanan traveled to Smuggler's Canyon in Texas in 1992 as he attempted to challenge the incumbent Republican in the primary. There he explained the need for a "Buchanan fence" to protect the United States from immigrants, who he said were responsible for fueling the country's drug epidemic.

"I'm drawing attention to the national disgrace," Buchanan said to a low-key crowd at Contraband Canyon, which included a food stand run by Mexican immigrants who sold sodas to Buchanan supporters. "The U.S. government's failure to protect U.S. borders from unlawful intruders, involving at least one million foreigners annually."

Buchanan's border raids and his stops in dying rural towns, where he rattled his cages over Bush's failed globalization efforts, took place months before his Houston speech pushed culture war into the American lexicon. By the time of his Aug. 17 speech before Congress, CNN's "Crossfire" pundit and former speechwriter to President Richard Nixon had completed his spectacularly unsuccessful challenge to President George W. Bush.

However, the three million votes cast in his favor were enough to earn him an olive branch from his opponent in the form of a prime-time seat on the main stage of the convention.

As American political historian Nicole Hemmer points out, Buchanan used this invitation to set the party's tone and agenda for the future, and he spent time on the high ground painting his picture of a post-Cold War world in which the walls were falling they encompassed Republicans. In an oil and gas city like Houston in the early 1990s, it should have easily gone under.

"There was a big recession in the early '90s that really got people, especially in industry, to think about the kind of decline and deindustrialization they'd been going through for decades at that point," says Hemmer. “Then came this new media landscape with conservative shows on radio and cable TV, particularly cable news and channels like MTV and Comedy Central, which are really pushing a mix of entertainment and politics. And this particular combination is really wild and provocative. And culture wars are perfect for this media environment.”

The city contradicts itself

Houston proved a source of controversy in the days leading up to and during the 1992 Republican National Convention. City and county officials spent more than a year preparing for the arrival of Republican delegates at the Astrodome. The venue became his soccer field and a third of the floor plan was cut out with curtains as a backdrop for the speakers, who addressed the crowd in red, white and blue, holding placards thanking Ronald Reagan and shouting, "Knock, I'm in the apartment." , snip!"

Outside the walls of the Astrodome, protesters from various groups clashed over issues ranging from abortion to police brutality and funding for the arts. Activists from the National Organization for Women rallied on the northwest corner of Mulworthy and Kirby to denounce the GOP's pro-life platform, clashed with pro-life counter protesters carrying plastic dolls. Members of Queer Nation and the AIDS Coalition to Unleash the Force (ACT UP) stormed a prayer lunch hosted by conservative televangelist Jerry Falwell outside the West Loop Holiday Inn with signs reading "Hate Is Not a Family Value."

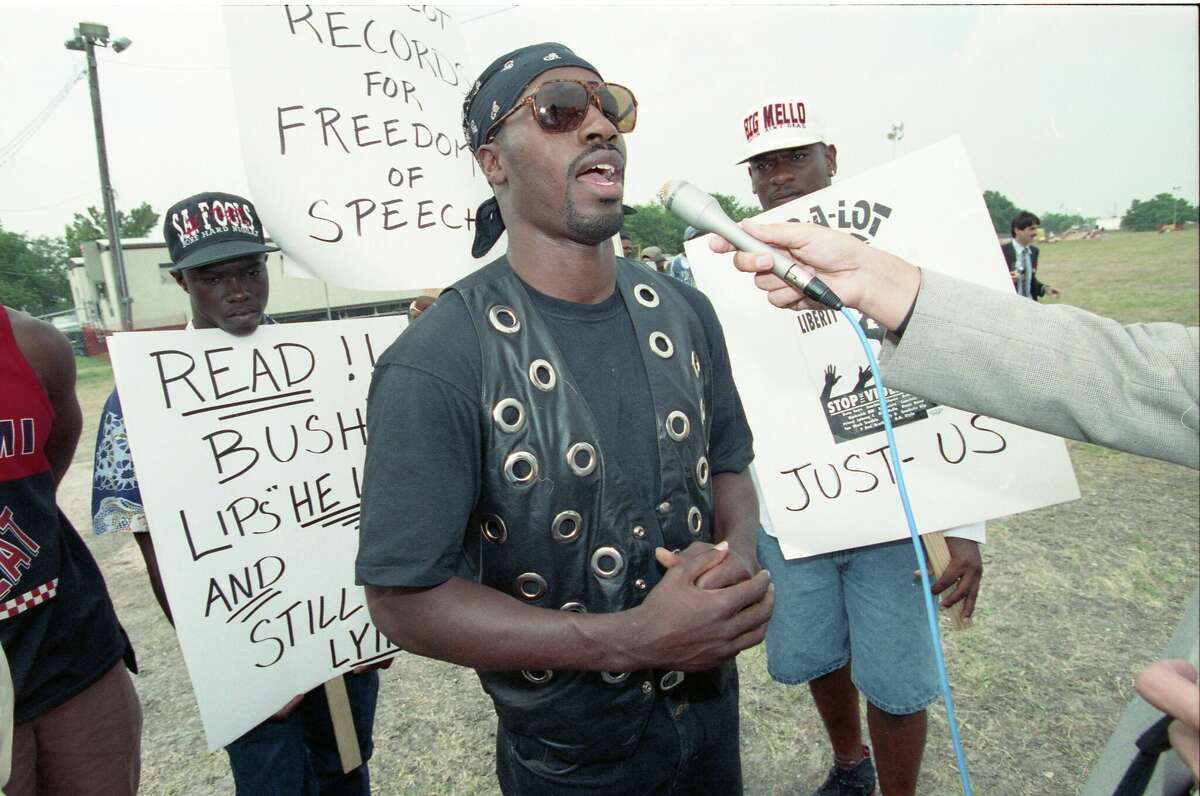

Rapper Willie D, who had just split from Houston rap group The Geto Boys, led a group of local artists with black pine coffins at a rally against police brutality and government censorship. Hundreds of young Houston artists formed the drum group Menil Collection to denounce Bush Sr.'s lack of support for the National Fund for the Arts.

On Fannin Street, Conservative protesters knelt behind railings outside Planned Parenthood's offices while HPD officers cordoned off downtown in preparation for the arrival of out-of-state delegates. Days before the start of the convention, recovering addicts used chainsaws to cut leaves along the street in Houston in advance of the national event in exchange for community service.

This set the stage for Buchanan's culture war policy. While Ronald Reagan impersonators like New York Congressman Jack Kemp delivered bombastic speeches appealing to the "bleeding hearts" of Republicans in 1992, Buchanan addressed the crowd with sharp, well-aimed cost-cutting attacks where politics as spectacle became commonplace.

"Buchanan's speech is quite dark and angry, although even as such an expert in the field, Buchanan is capable of eliciting laughter and a few chuckles," says Hemmer. “If you watch the video, [the crowd] really reacts to Buchanan. The crowd is with him when he talks about feminism and liberals.”

NBC's footage of Buchanan's speech confirms Hemmer's assessment: Bush supporters laughed non-stop as the former speechwriter mocked liberal "radicals" who had gathered in New York for the 2020 Democratic National Convention. 1992, an event Buchanan called "the largest opposition demonstration of all time." Dressing in American Political History. By the end of his performance, the NCR audience was completely in the hands of the expert and joined the Buchanan Gang to march in applause to his grand, battle-filled finale.

During Congressional week, Gov. Bill Clinton issued press statements highlighting the shifting trade winds within the Republican Party that were looming at Congress.

"This party, this Republican party, is definitely under the control of the party's bigoted far right," Clinton told the media on Aug. 20, the night the RNC shut down. Pat Robertson, Pat Buchanan, Jerry Falwell, Phyllis Schlafly, Party Wings. Now they are in control. They have George W. Bush where they want.”

Voices that want to be heard

However, this alliance of right-wing and centrist Republican elements in the Houston Astrodome would not be enough to win Bush Sr.'s re-election. Bringing right-wing commentators like Rush Limbaugh into his coffers at the Presidential Convention has turned public sentiment against the Republicans and after 12 years on the executive branch, the incumbent has lost 5.5 points. Clinton leads independent Ross Perot, a Texan who garnered a staggering 19.7 million votes on the third party list, by 37.5% of the vote.

Bush's non-re-election likely would have happened even if he had capitulated outright to neoconservatives like Buchanan, but the 1992 Houston National Convention proved one thing: the culture war would have become a major political message in the United States. strong form of communication. Complaints that continue to this day. This method is not without its flaws, Hemmer notes, most notably the culture war's inability to deliver more than the promise of retaliation for the voters' enemies.

"[The culture war] isn't necessarily about meeting people's material needs," says Hemmer. “Often people's frustration comes from feeling that the government is not responding to their needs, they feel that their economic downturn or they are losing power for various reasons and their voice is not being heard.

"If you want to get people interested, culture war themes are a great way to do that," says Hemmer. "But it alienates a lot of people because culture war is inherently and ultimately bad."

In the years since the 1992 Republican Convention, the seeds of right-wing unrest sown in the Astrodome and broadcast on television screens across the country have borne undeniable fruit in the way politics is handled in the United States. The names of the culture wars may change, with Buchanan and Limbaugh giving way to Trump and Carlson, but the jokes are as similar as they are ubiquitous every time you turn on the screen or answer the phone.

On the Houston platform, Buchanan floated the idea of "abortion on demand," a phrase echoed last month by Lindsey Graham in her proposal for a sweeping national law banning the practice of medicine after 15 weeks of pregnancy. Buchanan also championed "school choice," a term that has since become a Republican rallying cry for the privatization of public education and a central concern of leading Texas Republicans like Senator Ted Cruz and Gov. Greg Abbott.

In a 2017 interview with The Daily Beast, Buchanan himself acknowledged the origins of the culture war that sprang from his 1992 campaign.

"I was relatively shocked when [Trump] spoke out against trade and immigration and put America first," Buchanan said. "It's in my [campaign] hats."

special crown

Read More Houston in the '90s

over 90