[ad_1]

Illustration: Fran Pulido

In August 2023, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) revised its code of conduct in response to complaints about the online hounding of astronomers who had collaborated with alleged or known harassers. “We knew of several astronomers around the world who were being ostracized from the astronomical community,” Debra Elmegreen, president of the Paris-based organization, told Nature at the time. Examples included researchers having papers rejected and being excluded from conferences.

The IAU’s revised guidance raised a fierce debate and ethical questions from its members about how to respond when a colleague is accused of harassment. Should researchers collaborate with a known or suspected harasser? And if allegations are found to be true, should offenders be cited as authors, invited to write opinion pieces or be employed at another institution?

There are currently no universally accepted guidelines to help the scientific community respond to such situations, leaving people and organizations to muddle through on their own, which can compound the harm.

How to stop ‘passing the harasser’: universities urged to join information-sharing scheme

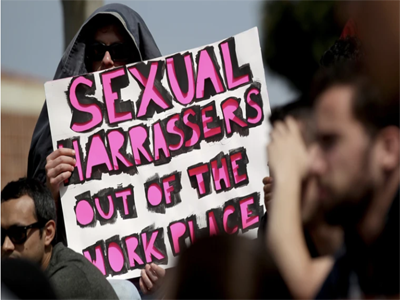

Academia continues to struggle with bullying and harassment, despite social protest movements such as #MeToo and #BlackLivesMatter drawing attention to it. According to Nature’s 2021 global salary and job satisfaction survey, 27% of the 3,200 self-selecting respondents said they had observed or experienced discrimination, bullying or harassment in their present position, up from 21% in 2018. In Nature’s 2022 graduate student survey, 18% said that they had personally experienced bullying, down from 21% in 2019. And in last year’s survey of postdoctoral researchers, 25% reported experiencing discrimination and harassment.

These behaviours create unsafe spaces in academia — particularly for women and minority groups — that reinforce inequalities1, drive researchers out of academia and can even put people at risk of physical harm2.

Because misconduct investigations are usually shrouded in secrecy, colleagues are often left to base their responses on rumours and hearsay, and unsure how to interact with an accused peer.

There are also several good reasons for closed investigations, including various competing interests around privacy and due process, many of them employment-law protections. Furthermore, survivors of harassment might not want their cases publicized, and those accused might want to defend their case without being tried in the court of public opinion first.

“Harassment is actually not an individual issue,” says Anna Bull, who is based in York, UK, and is the director of research at the 1752 Group, a UK organization that studies and advocates against sexual misconduct. “It is a community issue.”

Community strife

Faced with information vacuums, researchers and communities often take matters into their own hands by refusing to cite or collaborate with certain people (including both accusers and the accused in harassment and bullying allegations), not inviting them to conferences or into partnerships and excluding them from social events.

A 2022 study3 found that article citations dropped — by more than 5% — if an author was publicly found to have committed sexual misconduct. Most people learn about allegations through their peer community, says co-author Marina Chugunova, a behavioural and experimental economist at the Max Planck Institute for Innovation and Competition in Munich, Germany. “We’re in a very social profession, and their network matters a lot.”

But this study looked only at known and published cases of misconduct.

Marina Chugunova, a behavioural and experimental economist at the Max Planck Institute for Innovation and Competition in Munich, Germany, has studied harassment’s downstream effects.Credit: Max Planck Institute for Innovation and Competition

“Secrecy is the real problem,” says Sarah Batterman, an ecologist at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies in Millbrook, New York. In 2021 Batterman joined other women who spoke out about sexual misconduct at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) in Panama City. Batterman, who remains a research associate at the STRI, still does not know whether the person who she filed a complaint against resigned or was fired. He remains active in her field of research.

“There are so many cases where people just get removed from positions and go on to another institution. It’s ‘pass the harasser’ and they just get to keep on behaving in their bad way because no one knows,” says Batterman.

Joshua Tewksbury, who took over as director at the STRI in 2021, says that “reports of harassment and investigations are treated with strict confidentiality to safeguard the privacy and integrity of those who come forward. Our primary focus is on supporting those affected while ensuring that investigations are fair and thorough.” The institute has since overhauled many of its practices for handling misconduct cases.

Some funders, including the US National Institutes of Health and the US National Science Foundation, require disclosure if grant recipients are disciplined for harassment. This enables such organizations to decline requests for a principal investigator to transfer a grant to another institution, or request that an institution find a replacement principal investigator. Some organizations will ask prospective employees whether they have been disciplined for harassment. However, institutions can often be oblivious of an employee’s past.

Also, an alleged harasser might resign before being dismissed, Tewksbury told a Nature podcast last year. “We are not in a position of sort of making a blanket public statement. In fact, legally, we can’t [get] around those issues, particularly if someone quits,” he said.

Shining a light

Disciplinary processes are considered a human resources (HR) matter, and most HR information is confidential, explains Georgina Calvert-Lee, a barrister and employment-law and equality specialist at Bellevue Law in London. People have “a right to private life and a family life”, she says, and this is explicitly protected by employment law.

Calvert-Lee says confidentiality regarding investigations protects the fairness of the process on both sides and the evidence that witnesses give. Disclosing investigation findings also comes with pitfalls, she adds. A sacked employee could sue for wrongful dismissal and a former employer could be liable for damaging the individual’s reputation if the circumstances of their departure were in the public domain. Ultimately, UK employment law does not require universities to disclose such findings and so most institutions would not risk being sued, Calvert-Lee says.

Employment-law and equality specialist Georgina Calvert-Lee says that confidentiality around investigations protects the fairness of misconduct investigations on both sides.Credit: Laura Shimili Mears

In 2016, Julie Libarkin, a geologist at Michigan State University in East Lansing, became frustrated at how harassment cases in US academia were being reported in the media. She describes high-profile misconduct allegations as “bursts of light that then fade away”, adding, “It means we don’t shine a light on the problem.” So, she trawled the Internet for US harassment cases, finding 30 in one day. She then set up the open-access Academic Sexual Misconduct Database, which has more than 1,200 entries and includes only publicly documented US cases.

There are no definitive statistics on either the prevalence or the extent of confirmed findings of harassment and discrimination in academia. But, in a 2018 report that summarized studies on sexual harassment in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) fields, the US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine estimated that more than half of female faculty members and staff have encountered or experienced sexual harassment. In a 2022 survey of more than 4,000 self-selected early- and mid-career researchers in Brazil, 47% of women had experienced harassment at work. Only a small fraction of reported incidents will result in formal disciplinary action. Of those that result in a finding of misconduct, an even smaller number will be made public.

Most institutions encourage informal resolution first, says Libarkin. Even if a person acknowledges their wrongdoing and agrees to undertake counselling or training, there is no paper trail, she says. “There’s no requirement that informal processes be reported anywhere.” These cases are not in her database.

For cases serious enough to find their way into the public spotlight and onto her list, “there’s rarely one victim and there’s rarely one incident”, she says. And yet US institutions are not required to keep information illustrating a pattern of behaviour, and often the information is not made public. Some universities, such as University College London (UCL), allow formal warnings to expire, so that a few years after a finding of misconduct, it is disregarded in future disciplinary action. Furthermore, many institutions ask complainants to sign non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) as part of the disciplinary process, which prevents them from speaking out about what happened to them.

Freedom and safety in science

Astrophysicist Emma Chapman who is now at the University of Nottingham, UK, campaigned to ban NDAs following a two-year sexual harassment investigation by UCL, which was initiated by a complaint she filed during her time there as a PhD student. “I insisted on a confidentiality waiver,” she says, so that she could talk about some part of what happened. “You can’t fix the problem without exposing the problem.” The waiver requires her to give the institution two days’ notice ahead of talking about her case. In 2019, four years after Chapman’s initial complaint, UCL ended the use of confidentiality clauses or NDAs in settlement agreements with individuals who have complained of sexual misconduct.

After Chapman first went public about her experience, women reached out to her from all over the world to share theirs. “People were like, ‘I was raped, but I can’t say anything’ or ‘I was sexually assaulted, and I couldn’t say anything’, ‘I had to leave’, and ‘I’m under an NDA’,” she remembers. “And I realized that my case was deeply, deeply upsetting and shocking and — normal.”

Transparency is tricky

Total transparency about bullying and harassment cases can also be problematic, because many survivors might not want to disclose what happened to them, says Mark Dean, chief executive of Enmasse, a workplace behaviour-change consultancy company in Melbourne, Australia.

“There’s a reasonable chance that an unwanted announcement will further traumatize an individual,” he says, adding that respecting a survivor’s wishes is fundamental, and should inform any action. The complainant might want to put the matter behind them or they might fear other forms of career-damaging retaliation. Although many colleagues might guess who the complainant is after a suspected harasser leaves, this can be less traumatic than a public announcement, Dean says.

There are legal and employment restrictions that protect a person’s privacy. “Quite often we see organizations hamstrung by a range of conflicting interests as to whether they announce to the world that someone has been found guilty of misconduct,” Dean says. “They are subject to a whole range of employment privacy requirements.”

How hiring policies can help end workplace harassment

In the United Kingdom, disciplinary findings are seen as the personal data of the person accused, says Bull. That means it is illegal to share the findings, including the sanctions against the individual, with professional bodies and even prospective employers without the individual’s permission.

Calvert-Lee says that there are exceptions to the law when there is a legitimate purpose for sharing the information. If an employer asked for a reference, for example, a former institution could state that the person had been dismissed for misconduct. As things stand, neither party is required to request or provide such information and the new institution might not know to ask for such information, unprompted.

Bull’s 1752 Group is urging universities to try to remedy this problem by joining an initiative called the Misconduct Disclosure Scheme. The scheme, which is currently implemented by more than 250 organizations worldwide, aids the sharing of misconduct data between employers.

The lack of such open, transparent data makes researching harassment and discrimination difficult, too, says Chugunova. “From surveys, we know it is a huge problem, but the data is just not there.” Her 2022 research paper used data from the Academic Sexual Misconduct Database, and so was limited to cases in the United States. Social scientists have been saying for decades that there is no data, she says. “In 20 years, nothing has changed.”

Difficult discussions ahead

“Astronomy was at the front of the #MeToo movement in STEM by far, and now right at the front of the backlash as well,” says Chapman, pointing to the issue of harassment of alleged harassers and their allies, which the IAU was trying to address with its initial code-of-conduct revision. “And the things we see happening in astronomy are going to start happening in other fields as well in the next year or so. We have the opportunity right now to be the guinea pigs for academia and for higher education by having this very difficult discussion,” says Chapman.

In October last year, the IAU revised its code of conduct again to emphasize that “any form of physical or verbal abuse, bullying, or harassment of any individual, including complainants, their allies, alleged or sanctioned offenders, or those who work with or have worked with them, is not allowed”. Many members pointed out that this addition merely reinforced that harassment was prohibited — which had already been the organization’s policy.

Emma Chapman, an astrophysicist at the University of Nottingham, UK, campaigned to ban non-disclosure agreements as part of disciplinary processes.Credit: Emma Chapman

Chapman, who was critical of the initial changes, says that at least the IAU is trying to engage the problem. “There is no easy answer, but that doesn’t mean that we default to having no answer,” she says.

Ultimately, institutions and professional bodies need policies that are proactive rather than reactive, says Chapman. For example, conference organizers should have codes of conduct that lay out whether researchers who have been found guilty of misconduct can present at their event. “That way, you’re more legally protected. What’s not OK is, for example, to say ‘so-and-so can’t be part of this community’ and be vague about it,” she says.

Calvert-Lee says that excluding people from events is legally “tricky”. It could be defamatory to deny people access to events on the basis of rumours or allegations. But if an individual is found to have harassed or bullied others, an organizer could argue that excluding that individual reduces the risk to other attendees.

Professional societies such as the IAU have an important part to play. “What matters is the field — if you don’t have agreement across the field, it is kind of useless having an agreement in one university, or even one country,” says Chapman.

Calvert-Lee suggests that institutions should ask former employers to disclose the number of misconduct findings against a potential employee, or whether there were any outstanding investigations when the person left. In her experience, most UK universities supply “a very short two-liner, which says that a person worked here in this capacity from this date to that date, full stop” and would not voluntarily disclose extra information for fear of litigation.

Because academia is an extremely mobile community, Batterman suggests that academics should have a worldwide professional certification process. “Doctors and lawyers get professionally certified, and there’s an ethical review. If they violate their community norms, they can lose their licence. It should be the same in academia, whether it’s sexual harassment, sexual assault or bullying,” she says. But national efforts would be a valuable start, she adds, with various disciplines collectively deciding what actions would result in permanent expulsion from the academic community.

Dean advocates that organizations should take a hard line on sexual harassment and reclassify it as serious misconduct and thus a fireable first-time offence. He also urges institutions to report their anonymized statistics. They could regularly publish the number of findings on sexual misconduct and the number of exits under that policy, without naming survivors or their harassers, he says.

It’s a level of semi-transparency that could help communities to move forwards from harassment findings without causing the field or the individuals involved more harm. “Over time, people will see that the rumour mill starts, then there is a finding and then someone is no longer there,” Dean says. It also wouldn’t violate the competing employment and privacy laws.

“It is a workaround,” he admits. But importantly, it would allow people to see the consequences of such behaviour.

[ad_2]

Source Article Link