[ad_1]

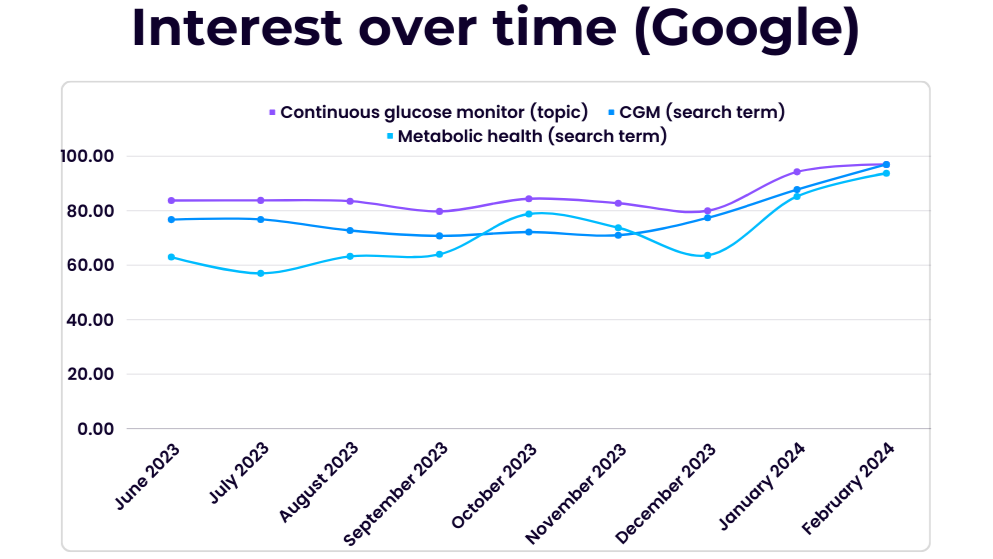

If you’re like me, you might never have heard of continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) until the last few months, if at all. However, if your online presence has found its way on to any health or wellness algorithms, you’ve almost certainly encountered at least one or two advertisements or endorsements for the technology.

That’s because these smart glucose sensors are being touted by manufacturers and lifestyle brands as the key to unlocking and improving metabolic health, despite having been invented primarily to provide diabetes patients with real-time glucose readings.

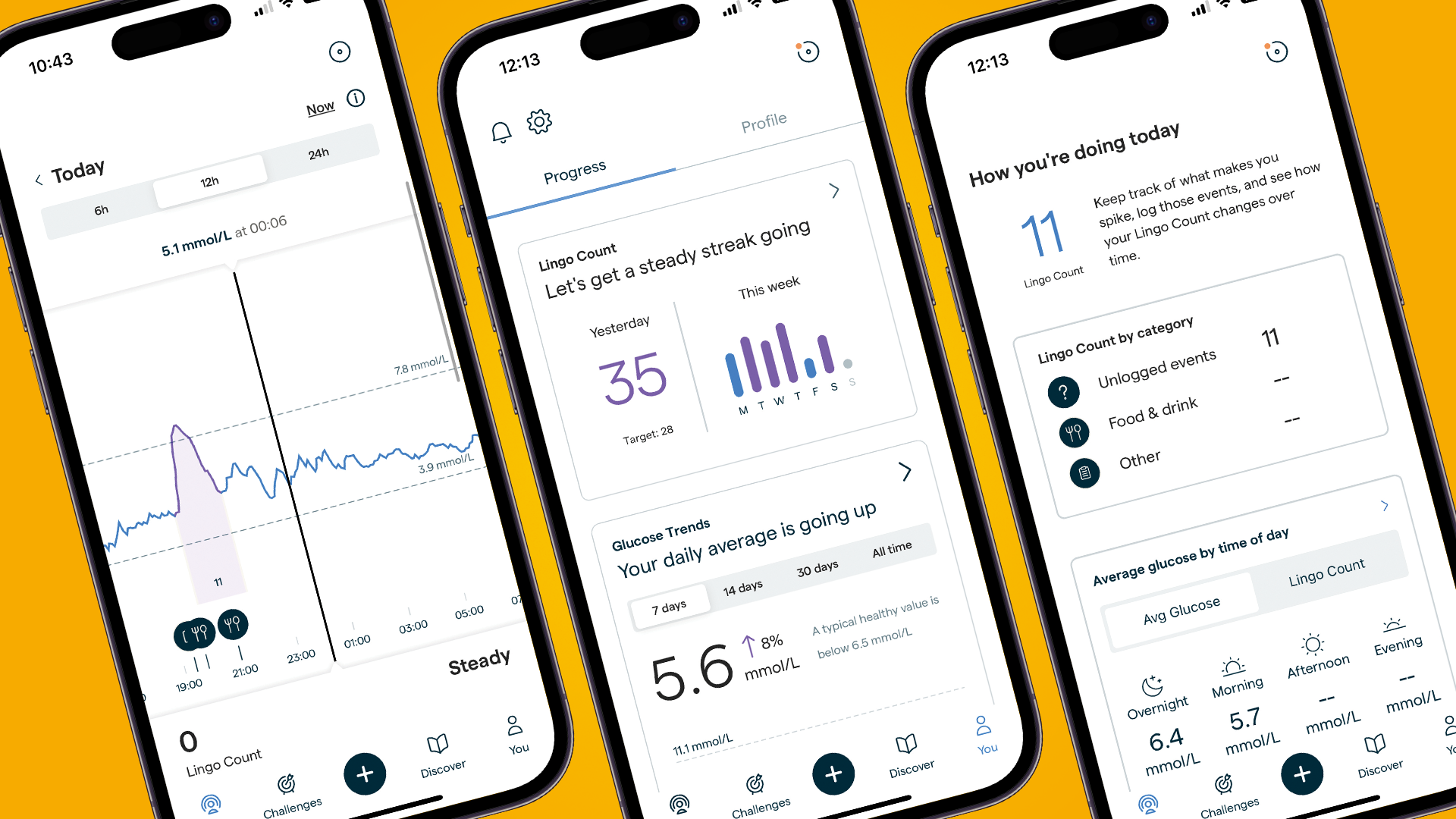

From Zoe and Lingo in the UK to Nutrisense and Levels in the US, new brands offering CGM-based lifestyle plans and health-tracking apps are everywhere. Even Apple and Samsung are racing to develop noninvasive glucose monitors to incorporate in some of the best smartwatches.

But what is metabolic health, and does the information generated by these devices provide any insight that can provably help non-diabetic users? These are the questions I sought to answer when I began my journey trialing CGMs this year.

So, in addition to testing out Lingo by Abbott and the Zoe diet, I’ve spoken with nutritionists, diabetes experts and CGM gurus to find out what all the fuss is about.

What is a CGM, and who’s it for?

CGMs pack some pretty fascinating technology. Once applied, they look pretty nondescript; just a white disc stuck onto your arm and rarely larger than 1.4-inches / 3.5cm in diameter. Under the hood, however, there’s a lot going on.

CGMs insert a subcutaneous (under the skin at the layer closest to your muscle) sensor, using an algorithm to estimate blood glucose concentration based on the levels they find in the interstitial fluid (found in the spaces between cells). They do it in almost real-time, with a delay of just 15-30 minutes depending on the sensor. This data is then transmitted to a companion app and translated into a glucose reading to show how your body responds to recently eaten foods.

I spoke with Dr. Mark J. O’Connor, Assistant Professor of Medicine and practicing endocrinologist, to learn more about how these devices are used in a clinical setting.

Dr. O’Connor is an Assistant Professor of Medicine at the UMass Chan Medical School in Worcester, Massachusetts, and a practicing endocrinologist at UMass Memorial Health Care System, particularly in the UMass Diabetes Center of Excellence. He’s also conducted a small research study on the utility of using CGMs to help diabetes patients in emergency departments.

He explains: “A CGM is a useful tool for people with diabetes, because it gives them a lot more insight into their blood sugar levels, and it gives us as healthcare providers more insight so that we can make the best recommendations.

“It also helps people make better decisions about exercise, food, and other factors that affect blood sugar levels. For many people with diabetes, it’s a Godsend.”

The technology has come a long way since 1999, when it gained Food and Drug Association approval for clinical use in the US. Abbott, one of three US companies manufacturing the majority of CGMs worldwide, is one of the first to take its technology into the consumer space; its consumer offering, Lingo, arrived in the UK in January, and pending FDA clearance is set to be released in the US later this year.

I spoke with Olivier Ropars, Division VP of Lingo Biowearables, about the company’s expansion into direct-to-consumer CGMs.

Ropars joined Abbott in 2022 to run Lingo, Abbott’s consumer Biowearables division, where he is currently overseeing the growth of the product as it comes to market in various regions. He previously held positions at eBay, StubHub and McKinsey.

The key benefit to direct-to-consumer CGMs, says Ropars, lies in understanding your metabolic health – which, broadly speaking, is the absence of metabolic disorders, including conditions such as type 1 diabetes, obesity, and inflammatory bowel diseases. They can also be vital tools in measuring the long-term effects of hypoglycemia (low blood glucose) and hyperglycemia (high glucose levels).

As Ropar explains, a series of studies conducted by Abbott employees and consultants found post-meal glucose spikes correlate to sleep and mental health difficulties and increased hunger. More worryingly, they were also associated with the development of type 2 diabetes and an “increased risk of seven out of the 10 leading causes of death in the US; that’s expected to be the same in the UK.” These include cardiovascular disease, liver failure, kidney failure, and increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s.

CGMs: Fad or fact

“The current healthcare system is entirely focused on curing diseases or trying to catch diseases early. There’s very little focus on disease prevention,” says Ropars, citing findings that health trackers such as pedometers have an “overwhelmingly positive” impact on people’s lifestyles. CGMs, he argues, will have the same effect.

Ropars says three groups of people have been particularly receptive to Lingo. The first is people, particularly athletes, looking to optimize their health and performance. These bio-hackers are a core demographic across many CGM offerings; the recently shuttered Supersapiens CGM-based platform (which also used Abbott sensors) enticed users with the promise they’d “never bonk again”, referring to the exercise-induced hypoglycemia endurance athletes can experience when they haven’t eaten enough carbohydrates. Indeed, early studies have shown CGMs might be useful for athletes in determining ideal carbohydrate intake – but as of yet, this isn’t proven.

The second and third groups are more general; people wanting to resolve age- or health-related issues who haven’t seen success in one-size-fits-all solutions; and those with a family history of disease wanting to monitor health and take preventative measures.

O’Connor can likewise see the benefits: “To me, it does make sense that giving people access to more information would be helpful. To see the effect on your blood sugar of routine exercise or a healthy diet is positive reinforcement to continue to make healthy behavioral changes.” A small study funded by Dexcom, another major CGM manufacturer, supports this, seeing a small group of people generally improve their lifestyle after using a CGM.

Lauren Johnson Reynolds, AKA the London Wellness Coach, is a homeopath, nutritionist, and health coach with a special interest in hormone balance following her own experience with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS). Early studies have shown a correlation between glucose tolerance, diabetes, and PCOS, which is why Reynolds tried out CGMs after giving birth led her HBA1-C to elevate to a near pre-diabetic range.

“There were certain foods and combinations that I felt wouldn’t cause any issues, but were spiking my blood sugar quite badly,” she says. “It was very eye-opening, and I became very aware of how stress impacted my blood sugar.”

Following a series of health difficulties relating to stress and PCOS, Reynolds turned to homeopathic solutions to relieve her symptoms, beginning a journey of healing and self-understanding that culminated in her studying an integrated Homeopathy and Nutritional therapy course. Now, she shares her knowledge, passion and holistic approach to wellness as a health coach.

A double-edged needle

While there’s plenty of buzz around the potential for CGMs, there’s perhaps not significant enough proof to convince some practitioners. Katherine Metzelaar, MSN, RDN, CD, founder and CEO of Bravespace Nutrition, is one of many concerned parties. “There’s this general desire to want to know what’s going on inside of our bodies – but it’s not as simple as that.

“We have yet to hear about any positive impacts of continuous glucose monitoring outside of the management of diabetes, and I think they cause more harm than good.”

Passionate about helping people battling disordered eating, Katherine Metzelaar’s approach is to help cultivate a positive food and body relationship by creating a weight-inclusive space and educating clients on the impacts of diet culture. Her specialism is in eating disorder recovery, body image concerns, and weight-inclusive nutrition therapy, which she practices using the HAES (health at every size) approach.

Metzelaar specializes in disordered eating and food positivity, and fears CGMs are another chapter in a legacy of illusory diet and wellness fads that contribute to an ineffective approach to health.

“It could lead to oversimplifying nutrition, increased stress and anxiety around food, and unnecessary restriction or inaccurate and inadequate advice around what to do with that information,” she says. “My recommendation is usually not to do it. Even for clients I work with that have diabetes, it leads to them feeling anxious when they see their glucose spike.”

She’s also broadly unconvinced by the usefulness of the data provided, especially the difficulty in parsing what specifically might have elevated glucose levels when eating different foods.

Despite her own positive experience, Reynolds has similar concerns about the broader use of CGMs. “I recommend them to a few clients but not the majority… When you step back and look at it, it’s quite extreme, but we’re so used to monitoring our sleep and our recovery, it’s become very normalized.”

“Modern society has lost track of hunger signals and thirst signals. We’re told to drink eight glasses of water a day and eat three meals and two snacks, and so that’s what we do. It’s taking away from that mind-body connection. So, although I think they are extremely useful for people who have blood-sugar issues, have a condition like PCOS, or want to try CGMs for a short amount of time, for the average person I don’t think it’s necessary.”

Metzelaar also has concerns about the self-led nature of many CGM platforms. “To my understanding, there’s no oversight from a doctor or a dietitian to interpret that information and add clarity to it.” This, she says, could lead users to change their behaviors based on what could simply be the normal curve of what happens during digestion.

Knowledge is power – until it’s not

As of right now, there are numerous consumer-based studies underway, including large-scale efforts being conducted by CGM platforms including Levels and Signos. In the UK, Zoe Health combines gut microbiome, blood sample, and bowel movement data with its CGM readings, the results of which can be discussed with a Zoe nutritionist. Clearly, there’s plenty of confidence from these providers that there’s something in this CGM craze worth fighting for.

That’s certainly the resounding take of Ropars, who says we’re only just beginning to unlock the potential of CGMs: “It’s not like buying a diet book; that may not work for everyone. A CGM provides personalized information, so you can make the adjustments that matter the most for you.”

So, are CGMs a fad or the future of wellbeing? As of right now, they don’t definitively support non-diabetics to improve their lifestyle, nor can studies fully demonstrate the biomarkers they track have a measurable impact on long-term health and wellbeing.

Still, the appetite for the technology and the research being conducted into metabolic health, blood glucose, and the relationship with long-term health means, for better or worse, we’re likely going to be seeing a lot more about CGMs in the coming years.

You might also like…

[ad_2]

Source Article Link