[ad_1]

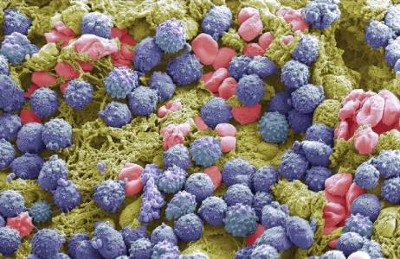

Long-term use of antiretroviral drugs can cause abnormal fat accumulation in people with HIV.Credit: Jose Calvo/SPL

People with HIV are the latest group to benefit from the new generation of anti-obesity drugs. If early data about the treatments’ effects are confirmed, the drugs could become key to controlling the metabolic problems often caused by anti-HIV medications.

Studies presented last week at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections in Denver, Colorado, suggest that the anti-obesity drug semaglutide not only helps people with HIV to lose weight but also reduces certain conditions associated with fat accumulation that are especially common in people infected with the virus.

Game-changing obesity drugs go mainstream: what scientists are learning

The number of people who are overweight or have obesity is increasing among those with HIV, driving interest among both affected individuals and medical providers in medications such as semaglutide, says Daniel Lee, a physician at the University of California San Diego Medical Center. At his clinic, which treats people with metabolic complications of HIV therapies, around 20% of patients already receive semaglutide or other drugs of the same class.

“For the most part, we’ve had very good experiences with these medications,” Lee says. But, so far, few studies have looked at the effect of the blockbuster anti-obesity drugs on people with HIV.

Unwanted side effects

Although the increasing incidence of obesity in people with HIV is similar to the trend in the general population, certain antiretroviral medications used to suppress HIV could contribute further to weight gain and weight-related conditions in these individuals1,2.

Semaglutide, marketed as Wegovy for obesity and Ozempic for diabetes, mimics a hormone called glucagon-like peptide 1, which helps to lower blood sugar levels and control appetite. In people who are overweight or have obesity, the drug promotes substantial weight loss3.

In a talk on 4 March, researchers at the Centers for AIDS Research Network of Integrated Clinical Systems, a group of HIV clinics across the United States, described their analysis of semaglutide use by 222 individuals receiving HIV care. The drug was associated with an average weight loss of 6.5 kilograms in around one year, or 5.7% of initial body weight.

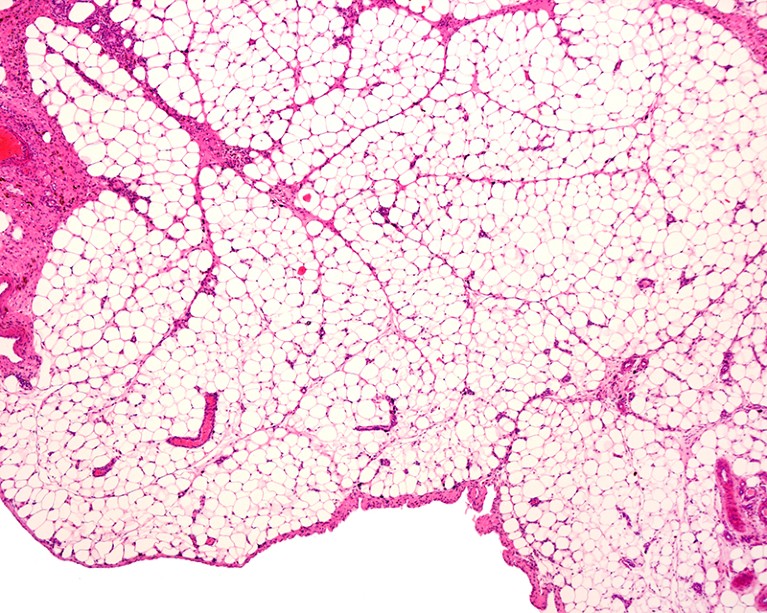

Helping a fatty liver

Antiretroviral therapies have also been associated with abnormal fat accumulation. One condition affecting 30–40% of people with HIV is metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, which is characterized by the build-up of fat in the liver. As the condition progresses, it can result in liver failure and cardiovascular disease. “We do know that people with HIV have a more aggressive form of fatty liver disease,” says Jordan Lake, an infectious-disease physician at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. But there is currently no approved medication to treat the condition.

Fatty liver disease: turning the tide

She and her colleagues evaluated the use of a weekly injection of semaglutide for around six months in people with both HIV and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. The results, presented on 5 March, demonstrated that 29% of participants had a complete resolution of the liver disease. “What we saw were really great clinically significant reductions in liver fat even over that short period of time,” Lake said at the conference.

But data from the same study show that participants taking semaglutide lost muscle volume, an effect also observed in other people taking the drug. Individuals who were 60 years of age or older were affected the most. Lee notes that older individuals with HIV are especially vulnerable to semaglutide-linked muscle loss and should be followed closely by health-care providers.

Taming inflammation

Another talk at the conference examined the use of semaglutide for a condition called lipohypertrophy in people with HIV. Characterized by the accumulation of abdominal fat, it “is associated with increased inflammation and carries an increased cardiometabolic risk”, says Allison Eckard, an infectious-disease paediatrician at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. “We have currently few treatments and those treatments often show ineffective response rates.”

Obesity drugs have another superpower: taming inflammation

In an earlier clinical trial, Eckard and her colleagues scanned the bodies of people with HIV and lipohypertrophy and found that semaglutide helped to reduce abdominal fat. They had presented results from that study in October at IDWeek, a meeting of infectious-disease specialists and epidemiologists in Boston, Massachusetts. And at the conference in Denver, the team showed that a blood marker of inflammation called C-reactive protein fell by almost 40% in study participants who took semaglutide compared with those who did not.

That could be an important effect, because even well-controlled HIV leads to a chronic state of inflammation, Lee says. And, he says, “if there’s increased inflammation, it can lead to end-organ disease of all sorts, including certainly cardiovascular outcomes, but also liver, kidney, brain, cognitive function, you name it”.

[ad_2]

Source Article Link