[ad_1]

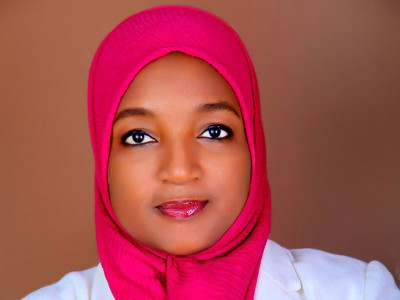

Being a parent is often seen as a career obstacle, but it can actually make you a better scientist, says nutrition epidemiologist Lindsey Smith Taillie.Credit: Paul Taillie

More than once in the past few years, in a variety of informal settings, I’ve overheard senior scientists recommend hiring people without children over those who are parents. Their reasoning, I gather, is that a parent might be smart and well-trained, but wouldn’t have the time or dedication to cut it in research. As a mid-career scientist with two young children, these comments floored me.

In my experience, these assumptions, typically aimed at faculty members or postdocs, are all too frequent. And although people tend to phrase their concerns in a gender-neutral way, about ‘parents’, they’re almost always talking about women. Women, who comprise only 33% of full professors despite accounting for more than 50% of the PhDs awarded each year, and who consistently have lower salaries than men across all ranks. Women, who still disproportionately do the bulk of domestic work, including childcare, around the globe. Although I’ve heard these comments more often from men, I’ve also heard female scientists essentially dismiss someone if they become pregnant, as if their career is over before really getting started.

The superhero skills needed to juggle science and motherhood

It’s true that being an academic woman with children is hard. In my field of global nutrition, it’s very common to have meetings at odd hours or need to travel at short notice. Dealing with school closures and frequent illnesses feels similar to playing whack-a-mole, needing to keep research moving while juggling childcare.

I have benefited from being white, heterosexual, married, neurotypical and working at a prestigious university. Crucially, I also benefit from having a husband, also a scientist, who does at least half of the childcare, cooking and cleaning, something that I think is still rare in heterosexual co-parenting relationships. Still, even with all of this privilege, it’s hard: there are many days when my brain feels shattered.

But, becoming a parent has also undoubtedly helped my career; both my rate of publishing and my number of grants won have increased substantially since my first daughter was born in 2017. I’ve become a more productive scientist. Here’s why.

Time scarcity

Those senior scientists who say that parents have less time are probably right: before I had children, I worked longer hours. I would go down rabbit holes into the early evening and often on weekends. I felt like I was always working and filling up all of my available time with research. But now, I write e-mails, papers and grant drafts like I am taking an exam: with intense focus and high speed. Having time constraints has forced me into a mindset of relentless prioritization, which has increased my scientific acumen and decision-making.

For example, last December, I was asked to present my research at a US Senate committee hearing on type 2 diabetes. I had only four days to put together a written testimony summarizing decades of data and build a case for why nutrition matters in diabetes prevention. My husband was out of town and, in a cruel twist of fate, one of my children got a throat infection. It was stressful, but I was able to draft the entire testimony in a single workday — something that, before having children, would have easily taken the entire four days. Also, because I knew that I’d need to rush off any second to tend to my sick child, I was able to push through my anxiety about writing such an important document and focus on getting pen to paper.

Why two scientist-mums made a database of parental-leave policies

Arguably, you could achieve this effect without children by having stronger work–life boundaries. That’s great, but it never worked for me. Having a non-negotiable deadline of school or day-care pick-up forced me to let go of my perfectionist tendencies, supercharging my productivity.

A fresh perspective

Becoming a parent also gave me a first-hand perspective on my field of nutrition. For example, similar to most young children, my three- and six-year-olds are picky eaters, and it’s been a challenge for me to get them to try new foods and eat veggies while also keeping food waste to a minimum. From social media, I discovered that giving my daughters tiny portions presented in a cute way — for example, a single broccoli floret with a toothpick and dip or a few spoons of soup in a colourful cupcake tin — helped with this. These experiences with my own children have helped me to incorporate families’ perspectives into my research design and to test interventions to prevent household food waste, increasing the chances that our interventions will be more effective for more people.

Parent networks

Even more importantly, becoming a parent has allowed me to create networks. I collaborate with colleagues who are also parents, and sharing our experiences has helped us to become friends, able to empathize and help each other out in a pinch, with work or with parenting.

Lindsey Smith Taillie’s experiences as a mother have helped to improve her food-waste intervention designs.Credit: Hacienda Mucuyche

This network has extended far beyond my immediate colleagues, too. Through the social-media platform Facebook, I have found an online community of academic mothers, which has become a treasure trove of help and advice. More than just tips on sippy cups or football clubs, people in the group share the hidden rules of playing the academic game, from handling job searches as a couple of two academics to going up for tenure or accepting tough grant reviews.

The networking benefits of parenthood translate to the team science, too. Sharing experiences about children helps to build rapport with collaborators — we’re able to bond over our common scientific challenges and laugh about our children’s silly stunts.

Emotional intelligence

Parenting has also made me a more effective teacher. For example, because my older daughter is obsessed with mythical creatures, I’m the proud owner of a giant inflatable pink unicorn costume — something that I have worn in class to demonstrate the power of food marketing, when discussing the Starbucks pink unicorn frappuccinos. It was silly, but that silliness has been helpful for connecting with students. Beyond pink unicorns, telling stories about my children in the classroom has made me more relatable and helped me to show key points about nutrition by invoking real-world examples. Parenting has helped me to expand my horizons and relate more to my students.

Could roving researchers help address the challenge of taking parental leave?

Being a parent has made me a better mentor, more able to support students who have children and helping me to treat all students as whole people, with a life outside science — whether or not that includes children. Because of my own experience, I feel better equipped to help my students to integrate the facets of their lives and find what balance looks like for them. It’s been difficult to speak out publicly about both the challenges and merits of parenting as a scientist. When I push back against things such as out-of-hours meetings, I worry about increasing biases against parents and especially mothers, perpetuating challenges to hiring and retaining them in the scientific workforce. But as time goes on, and I see these biases persist, I think that now is the time to speak up and be clear. Parenting isn’t my scientific kryptonite; it’s my superpower.

[ad_2]

Source Article Link