[ad_1]

Interactive therapeutic robot Paro keeps a resident company at a nursing home in Japan.Credit: Noriko Hayashi/Panos Pictures

Clara Berridge, an ethicist at the University of Washington, Seattle, recalls a story told by a colleague to a group of health-care and social-work students.

Nature Outlook: Robotics and artificial intelligence

An older man in a nursing home was given a robot that looked like a stuffed animal for companionship. He became attached to it and when he later fell ill and died, the nursing-home staff found him clutching his robot companion.

When the class was asked to offer impressions of the scenario they were split: either they thought it was beautiful that he wasn’t alone in his last moments, or they felt it was tragic to die without a human connection.

Robots are an increasingly popular form of therapy for older people with dementia. It’s been suggested that social robots, on which much of the research has been based, can improve people’s moods, increase social interaction, reduce symptoms of dementia and give carers some much-needed relief.

But some researchers are beginning to question if these devices are ready for widespread use with this population. The research proving robots’ worth is sparse, and there are ethical concerns — especially around the idea that their use might reduce human contact in a population that is dearly in need of it.

“If we’re going to invest resources in elder care, I want more staff in the facility so they don’t die alone,” Berridge says. Her grandmother passed away on her own in an understaffed nursing home during the COVID-19 pandemic. Berridge’s grandmother didn’t have the option of a robot companion, but Berridge would not have wanted that for her anyway. “There are so many other things I would choose for her before a robot,” she says.

Early adopters

The robots being used in therapy for older people and people with early cognitive decline fall into two broad categories: service robots and social robots. Service robots are designed to help people in their daily lives, such as by assisting with household tasks or mobility. Developing a robotic assistant that can navigate the home and safely interact with people and objects in its environment remains technologically challenging, however.

Paro robots, shown charging, are among the most common examples of social robots.Credit: FRANCK ROBICHON/EPA-EFE/Shutterstock

As a result, social robots intended to offer companionship and provide cognitive stimulation are a more common sight in care settings for older people. Some are humanoid in design and intended to act as ‘intelligent’ companions, holding rudimentary conversations and leading games and activities. Other social robots aim to mimic pets that can respond in some way to a person’s voice and touch.

Animals (often dogs) have been used in care settings to help residents to become more social and less agitated, and to improve their quality of life. But animals require a lot of care, whereas a robot pet does not. The most common example of this kind of social robot is Paro. Rather than a dog, the robot, which was designed in Japan, looks like a baby harp seal. A seal was chosen because it would be familiar and approachable, but it is not a common pet so a person would not immediately spot differences between its behaviour and that of the real animal. Paro is typically used to provide a form of pet therapy to older adults in assisted-living facilities, offering companionship and encouraging interaction between residents of the facilities and staff during therapy sessions.

Lillian Hung, creator of the Innovation in Dementia care and Aging (IDEA) lab at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada, purchased the furry bot in 2017 to use with people with dementia who had been admitted to Vancouver General Hospital. Initially, she used it in group therapy for people with dementia, and to help people who were reticent to talk during admission and discharge. But over time, Hung found more uses for Paro.

In one case, the robot came to the aid of a patient in accident and emergency who was hitting staff who came near him, and who kicked a laboratory technician trying to take a sample of his blood. “He had a cardiac condition that needed diagnostics and we had two choices: physically or chemically restrain him, or leave him alone,” Hung says. “Both options were not good.”

Instead, Hung placed Paro in the man’s lap. Paro turned its head as if waking from a nap, opened its eyes, and looked up at the patient. The man asked the robot if it had eaten lately. When Paro started moving around, the man began petting it. While he was engaged with Paro, the staff were able to perform the tests that they needed.

“I hadn’t planned to use the robot for that reason, but in the moment it was useful,” Hung says. “The patient had quality care and safety, and the staff were able to get their work done.”

In 2019, Hung reviewed 29 studies of Paro’s use in older-person care settings around the world with people with dementia1. She found three main benefits of the bot: reduced negative emotions and behaviours among patients, better social engagement and improved mood and care experience. “For an older person who is frail and struggles with language, the robot doesn’t judge,” Hung says. “It offers an unconditional presence. Regardless of what they say, it is always happy to listen.”

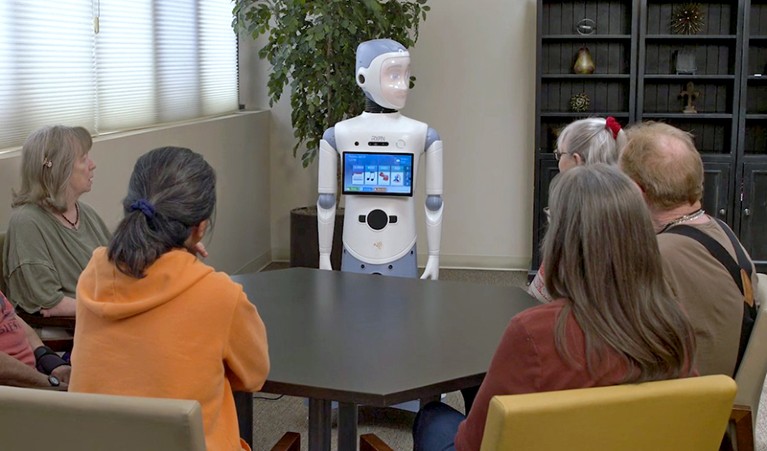

Creators of other social robots think that they could also be beneficial for this population. In 2020, Mohammad Mahoor, an electrical and computer engineer at the University of Denver in Colorado, built the third iteration of a humanoid companion robot he calls Ryan, which he began working on in 2013. The robot can recognize speech and facial expressions, and is designed to help reduce social isolation among people with early-stage dementia or depression by engaging them in conversation. Ryan can also remind people to take medications and can lead mental and physical games.

“Mostly these people live alone, their mood is down. We want to improve their quality of life,” Mahoor says. “When you engage residents, they are happier and their family members are more satisfied.”

Mahoor has carried out research in assisted-living facilities with Ryan. In one study, six older people with early cognitive decline were given around-the-clock access to Ryan for 4–6 weeks2. The participants reported enjoying interactions and conversations with Ryan and feeling happier when it was there. However, they did not report feeling less depressed after talking to the robot, and said it was not the same as talking to a real person — a distinction Mahoor understands. “We’re not replacing human interaction, just filling in the gaps,” he says.

Ryan is currently being used in two assisted-living facilities near Denver. The robot stays in the common area. Residents have a card that they can tap on it to spend 30 minutes each day talking, playing games or doing other activities.

Arshia Khan, a computer scientist at the University of Minnesota Duluth, is also working to show that robots can improve the quality of life of people with dementia. Humanoid companion robots, she says, can engage and stimulate people and reduce levels of anxiety and depression. They can also provide respite for carers by leading bingo sessions and playing games with residents in assisted-living facilities.

In one study, Khan and her colleagues placed Pepper and NAO — two humanoid robots built by the firm Softbank Robotics in Tokyo, and then specially programmed by Khan — in eight nursing homes in Minnesota. Surveys were conducted before and after implementing the robots. Compared with nursing homes that didn’t deploy robots, residents of facilities that did felt happier, more cared for, and less tired and frustrated after engaging with the robots3.

Cautious attitudes

Hung expects some resistance from carers to the use of robots. “Not everyone is ready to have robots,” she says. “When we did interviews with organizational leaders, they said money wasn’t the issue — their staff weren’t willing to work with robots.” While running a focus group at one care home, Hung and her colleagues returned from lunch to find the robot that they had brought with them not only unplugged, but wearing a paper bag over its head. “They were worried it was secretly recording them,” she says.

Companion robot Ryan is currently being used in two assisted-living facilities in the United States.Credit: Loclyz

Some older people also have concerns. In a 2023 study led by Berridge, 29 people living with mild Alzheimer’s disease were asked how they felt about robots and other assistive technologies4. Their key concerns were privacy — they wanted to know if the technology was monitoring them — and loss of human connection. Most participants said that they would prefer visits and phone calls from friends and family, or social outings and activities, over what a robot could offer.

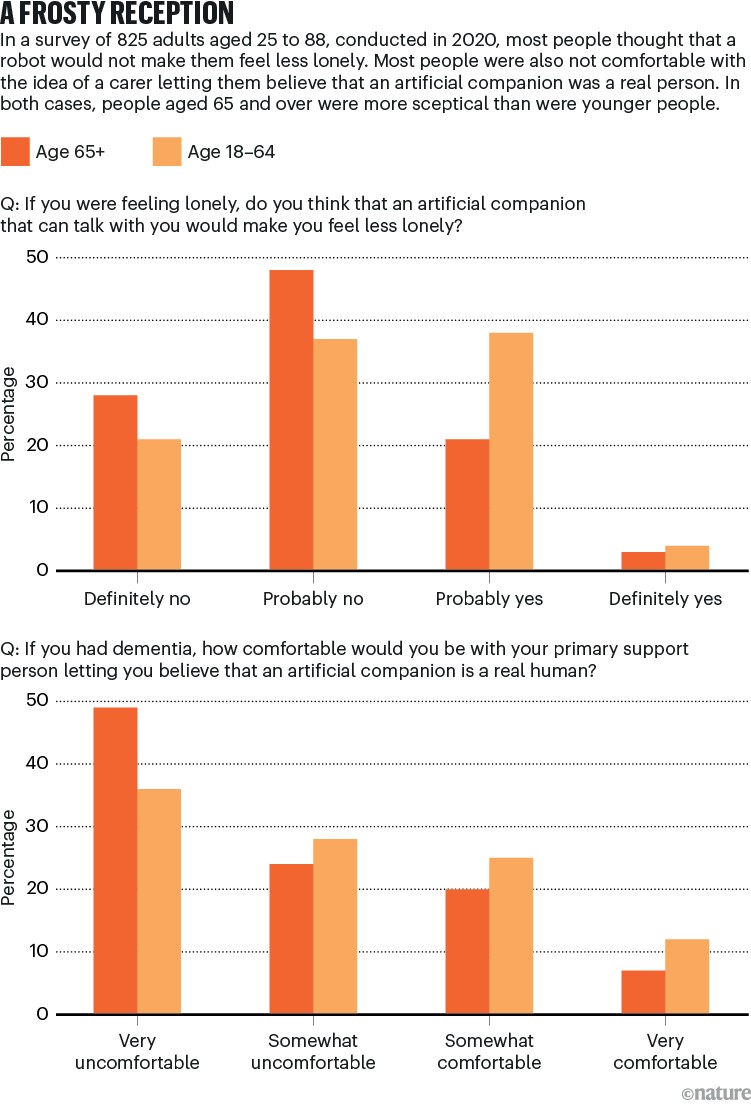

In a separate survey of adults who were generally tech-savvy, respondents described social robots as “creepy,” “manipulative” and “unethical”, and said that they offer only the illusion of intimacy5. Most thought that an artificial companion would not make them feel less lonely (see ‘A frosty reception’).

Ref. 4

They were also uncomfortable with the idea that a carer might let them believe that a robot was a real person if they lacked the cognitive ability to know for themselves. Berridge says that this is an issue on which ethicists are split. Some think that if the belief soothes people, then the deception, intentional or not, shouldn’t matter. Others see it as potentially taking advantage of extremely vulnerable people. “Concerns consistently arise over the possibility of withdrawing human interaction and touch, dishonesty, and potential for diminished dignity, which philosophy-trained ethicists will tell you needs to be protected — even and especially when people lack autonomy,” Berridge says.

Uncertain benefits

In addition to concerns that older people and their carers might not be comfortable with social robots, there are also questions about the utility of these devices.

Some users with cognitive decline showed higher stress levels after using the communication robot Chapit.Credit: Tomohiro Ohsumi/Getty Images

In a 2022 meta-analysis of 66 studies of companion robots6, ‘telepresence’ communication robots, assistive robots and multifunctional robots being used to support people with dementia, Clare Yu, who studies dementia prevention at University College London, and her colleagues found that many of the robots were generally liked by study participants and could feasibly be used in a nursing home. And most studies reported that the robots did what the authors anticipated: relieved loneliness and isolation, reduced anxiety, and improved quality of life. But the researchers noted significant difficulties as well. Paro, for instance, is heavy, expensive and noisy; humanoid companion robots tend to have speech-recognition issues; and telepresence and multifunction robots were difficult to use.

Yu and her colleagues also don’t think that the design of these studies was sufficient to provide compelling evidence of benefit to people with dementia. According to Yu, many studies didn’t compare robots with other forms of care, such as human interventions. Sample sizes were often too small to draw conclusions, some studies didn’t use well-validated outcomes, and many didn’t appropriately randomize their cohorts. As a result, despite seemingly positive results in many cases, Yu and her colleagues concluded that there was no clear evidence that robots improved people’s quality of life, cognition or behaviour.

“Before I did this meta-analysis, I was really excited,” Yu says. “I thought robots were something that could be used in the future for people with dementia.” She now has serious doubts. “I think they are something that can be used in the future, but not at this present moment. We need some time to do more research to be able to say they are definitely beneficial.”

Another 2022 review7 that analysed nine studies of Paro suggested that the seal robot could improve quality of life for people living with dementia and reduce their use of medications. However, the authors similarly tempered their conclusion by noting that the studies that they analysed were mostly of low to moderate quality, meaning the authors were “cautious to make positive comments on the role of Paro”.

A 2020 study8 from a team of researchers in Japan went so far as to suggest that communication robots might be detrimental for some people with dementia. Twenty-eight older people, 11 of whom had cognitive decline, received sessions with Chapit, a stuffed-toy robot with speech recognition that can play games with users. Measurements of electroencephalogram (EEG) activity and salivary cortisol levels, taken before and after sessions, showed higher levels of stress among the participants with cognitive decline after using Chapit, but not among those in the group without cognitive decline. People with cognitive decline also reported not enjoying their time with Chapit, whereas people without cognitive decline did enjoy it — a finding that matched the EEG results.

A study last year9 from the same group used EEG activity to determine whether Chapit activated participants’ posterior cingulate gyrus and precuneus — parts of the brain that affect reflection, self-consciousness, imagination and prediction. In people without cognitive impairment, these areas were activated by the use of Chapit. In people with cognitive impairment, however, there was no significant change in brain activity.

The allure of technology

With efficacy being questioned, and signs of resistance among carers and prospective users, widespread adoption of robots in older-person care settings faces clear obstacles. “I don’t feel we are ready to have large-scale implementation,” Yu says.

Arshia Khan uses a robot to run cognitive-stimuation quizzes with care-home residents.Credit: Devonna Palmer

She thinks that higher-quality studies and randomized control trials with the power to show clear benefits need to be done first. Then, the findings need to be weighed against the cost of the intervention. “I don’t think there is anyone doing economic evaluations looking to see if the money spent is worth the benefits we gain,” she says.

It took Mahoor upwards of US$6 million to get to the current iteration of Ryan. He has seven units for which he is looking for buyers. Most care homes he has worked with cannot afford to purchase Ryan, so the robot will also be provided through a lease of $1,200 a month for 10 users. Khan, meanwhile, says that the base price for the robots she has worked with is $37,000, not including software, maintenance, or training and support. These costs have fuelled concerns that, should the robots prove effective, they will be out of reach of all but the most well-funded and exclusive care homes.

Caleb Johnston, an anthropologist at Newcastle University, UK, who has studied the ethics of using robots with ageing populations, says that in many areas, including in the United Kingdom, social care is chronically underfunded, even as money pours into social robots. Although “these may help with social and emotional support” he says, the system will still rely on poorly paid carers, often from overseas, “to do the messy work”, he says.

Berridge also thinks it is important that the needs of the people whom the technology is supposed to help are not lost as it rapidly improves. “Are we designing robots with and for people living with dementia? Or are we designing to manage people living with dementia?” she says. “We risk undermining solutions with wider and deeper reach when we don’t do an honest assessment of the nature of the problem being targeted.”

“There’s a lot of hype,” she adds. “I would say that tends to squeeze out critical questioning.”

[ad_2]

Source Article Link