[ad_1]

SpaceX’s Falcon 9 has become a workhorse of the private satellite launch vehicle market.Credit: Associated Press/Alamy

Who Owns the Moon? In Defence of Humanity’s Common Interests in Space A. C. Grayling Oneworld Publications (2024)

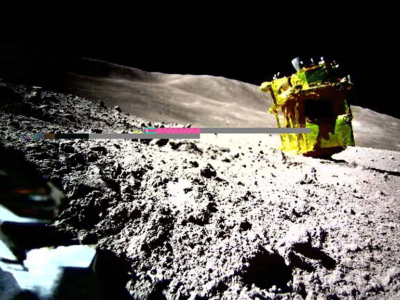

The Moon seems to be back on everyone’s radar. NASA’s Artemis mission is expected to shuttle humans back to the lunar surface before the end of this decade. In the past year, Japan and India have successfully landed rovers there; Luna 25, a Russian effort almost half a century after the nation’s last, almost made it, but crash landed.

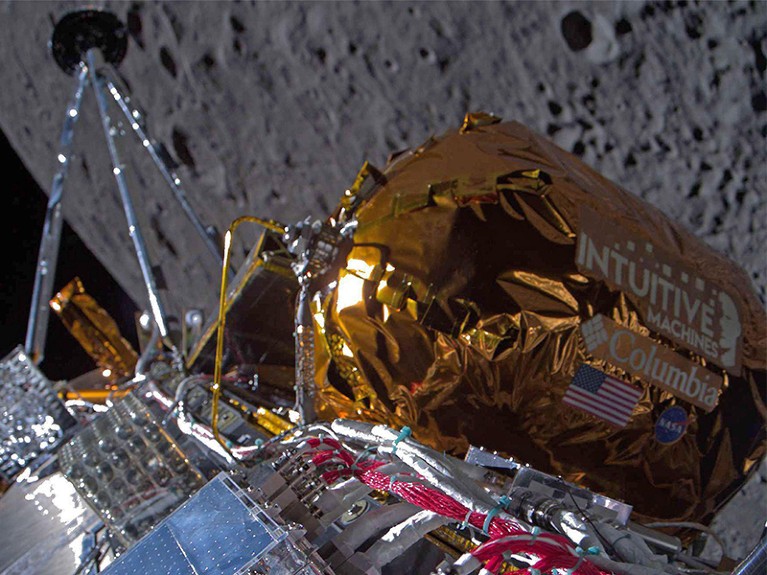

Several non-state actors are also stepping into the fray, with the space-exploration company Intuitive Machines, based in Houston, Texas, last month becoming the first private firm to complete a lunar touchdown — a feat that sent the company’s stock price soaring.

The fallout and consequences of this renewed clamour for the Moon is the subject of UK philosopher A. C. Grayling’s latest book. In Who owns the Moon?, Grayling explores one facet behind the interest in Earth’s pockmarked neighbour — a quest for resources.

Japanese Moon-lander unexpectedly survives the lunar night

India’s mission, for instance, was squarely aimed at exploring the Moon’s southern pole — a probable storehouse of frozen water, which could be converted into oxygen and rocket fuel. Grayling warns that human greed and national rivalries could set off a lunar ‘gold rush’ once the investment and engineering barriers to extracting extraterrestrial materials are surmounted. He calls for an urgent re-examination of the laws that govern space exploration.

Who owns the Moon — and perhaps more broadly, who owns outer space — is a complex, legally loaded question that has been asked since the space age commenced. Although a layperson might assume that there are no laws governing the exploration of the cosmos, international agreements, such as the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, do exist. Grayling’s contention is that such arrangements, negotiated under the auspices of the United Nations, are essentially cold war-era arms-control pacts, focusing primarily on prohibiting nuclear weapons in outer space and preventing any single country from claiming sovereignty over celestial bodies.

Trillion-dollar industry

Although this agreement has staved off major conflicts in space over the past nearly 60 years, the nature of space exploration has changed remarkably since then. For starters, private firms are now able to exert substantial influence on government-run space programmes. Private actors such as the US spacecraft manufacturer SpaceX, based in Hawthorne, California, already own a majority of the low Earth orbiting satellites. In 2022, the author states, the space industry was estimated to be worth US$350 billion and is projected to grow to more than one trillion dollars over the next two decades. Under these circumstances, the presence of intentionally vague and ambiguous terminology in existing international agreements — such as outer space being a “province of all mankind” held for the “common interest” — leaves room for misinterpretation.

If lunar bases end up becoming a reality, the existing legal framework will need an update. Without a bold new global consensus, Grayling predicts, a space ‘wild west’ is going to emerge.

In the absence of a concerted global dialogue, individual countries are pushing ahead with their own laws, such as the US Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act of 2015. Similar laws are being written or enacted in India, Japan, China and Russia.

Peace in space

Drawing on observations made by the UN’s Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space, Grayling writes that space law is getting more fragmented, thereby increasing the potential for conflict. An international regime that gives general guidance on most space-related matters — supplemented by a set of multilateral institutions that can support enforcement and adjudication — is imperative, he writes. Individual states can then focus on domestic licensing regimes for globally agreed activities. Whether one will come before the other is still an open question, but the signals point to domestic regimes moving faster than global governance.

The book’s main contribution is perhaps its chapters that document historical precedents, which offer lessons on how to set up mechanisms to facilitate global cooperation. According to some, the 1959 Antarctic Treaty is a shining example of a multi-party agreement that has kept narrow national interests at bay. However, it is important to point out that several signatories continue to maintain territorial claims. The law of the sea, a set of international agreements on the commercial exploitation of the oceans and the deep-sea bed, offers another template. However, these examples cited by Grayling do not necessarily transpose readily to outer space.

Last month, Intuitive Machine’s Odysseus became the first module manufactured by a private firm to land on the Moon.Credit: Zuma Press/Alamy

For instance, the law of the sea is the product of hundreds of years of negotiation and power tussles between diverse competing actors — a body of collective knowledge that is unavailable to a young field such as space exploration. And Grayling doesn’t discuss the analogies with international environmental law, which would have been more relevant. For most of human history, the planet wasn’t conceived of as an environment, although today it is. A profound legal reimagination is taking place as a result. If outer space is set to become a part of our immediate environment, then there could be lessons to learn from the ongoing climate change-induced reconsideration of the nature of resource exploitation here on Earth.

Without an overarching governance structure, disputes in space can be hard to deal with. Currently, when a conflict arises between two space-faring nations, not only does the vagueness of international space law ensure that there is no clear process to engage in consultation, there is also no mechanism to pin accountability. This is clearly a choice exercised by the currently dominant players who can, as a result, interpret the phrase ‘freedom of outer space’ in any way they choose.

The 1972 Space Liability Convention — a treaty that is pressed into service in case of injury to persons or damage to property owing to space-related activities — has been officially invoked just once, when a Soviet satellite deposited radioactive debris in Canadian territory in 1978. The Soviets had to pay Can$3 million (at the time around US$2.5 million) to settle the dispute.

Soon, such conflicts might spill over, as our conception of ‘damages’ expands to potentially include activities that harm the common environment that lies beyond national boundaries. Grayling repeatedly invokes the late-nineteenth century’s Scramble for Africa as a cautionary tale of what might happen if humanity’s worst instincts are let loose. At the very least, Grayling writes, our successors in the second half of this century and beyond will not be able to say: “no one warned us; no one reminded us of what history shows could so easily go wrong when it is considerations of money and power that alone drive events”.

The next generation

It is precisely to enable such wider debate that I focus so much of my effort and outreach on building the capabilities of African youth in the domain of space governance. According to the World Economic Forum, more than 40% of the global youth population will be African by the end of this decade. They are an important stakeholder, and they are the custodians of our collective space future.

When I was a trainee lawyer working for the Nigerian space agency nearly 17 years ago, my area of specialization was the application of international environmental law to space debris. Today, space junk is a global and increasingly mainstream concern. This is why genuine international cooperation is essential. The best ideas can come from anywhere. Diversity should build trust.

Simulated Mars mission ‘returns’ to Earth

Looking ahead, if I can indulge in some crystal-ball gazing, it seems likely that institutional and state governance mechanisms for managing the Moon — and outer space — will become a priority area in the coming years. Usually, such international arrangements tend to arise when there is a real risk of conflict. Despite the prevailing narrative about a second space race, there is currently little appetite for international dialogue on space-related matters that limits the freedom of the dominant actors. But this could change. What happens when the middle powers rise?

International space law is unique because the state is directly responsible and liable for all activities undertaken by its citizens, including those in the private sector. Given that some private space firms have more wealth and power than do many space-venturing nations, the scrutiny on these non-state actors will only increase.

Any future dispute-resolution mechanisms must balance inclusivity and justice, and acknowledge that space commercialization is a deep national security concern for many states. What happens in outer space should inextricably be linked to developmental debates on Earth. Otherwise, although space might nominally be for the ‘benefit of all’ — as per the Outer Space Treaty — a select few nations or companies could indulge in rapacious over-exploitation. So, we need to seriously ponder who will benefit and what will comprise the common interest.

Although Grayling does not address all these concerns in depth, Who Owns the Moon? is still an important introductory text on the issues and challenges that humanity will have to confront as it ventures to the Moon and beyond.

[ad_2]

Source Article Link