[ad_1]

Vilnius, Lithuania’s capital, will be home to Europe’s largest biotechnology hub.Credit: Getty

Many of those involved in Lithuanian research say that the Baltic country’s scientific ambitions stem from a desire to make its mark after becoming the first of 15 republics to break away from the Soviet Union in 1990, a year before the formal collapse of the union.

Researchers point to a culture of collaboration, rather than one of competition, in which scientists are keen to help each other. This is made easier by the country’s small size — it has a population of 2.8 million.

This year, Lithuania marks a more recent anniversary. Twenty years ago, it joined the European Union, a move that further enhanced its collaborative credentials and ambitions in the life-science and biotechnology sectors (see ‘Landmarks in Lithuanian science’).

In 2020, for example, the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) chose Vilnius University’s Life Science Center, which houses three research institutes (biochemistry, biotechnology and biosciences), to partner with it to develop genome-editing technologies. The partnership is one of seven created around the world since 2019 — the collaborations typically last between five and nine years.

Last November, Lithuania’s President Gitanas Nausėda announced that Bio City, Europe’s largest biotechnology hub, will be built in Vilnius. The move forms part of a €7-billion (US$7.5-billion) investment led by the Northway group, which comprises 17 companies in the fields of medicine, health care, biotechnology, pharmaceuticals and investment, and is supported by private investors and loans.

Lithuania’s ambitions in the life sciences and biotechnology have not gone unnoticed. The intergovernmental Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) maps different countries’ biotech research-and-development investment as a percentage of total business enterprise research and development. According to this measure, Lithuania comes third, behind Belgium and Switzerland, based on 2022 data. The data exclude the United Kingdom and China.

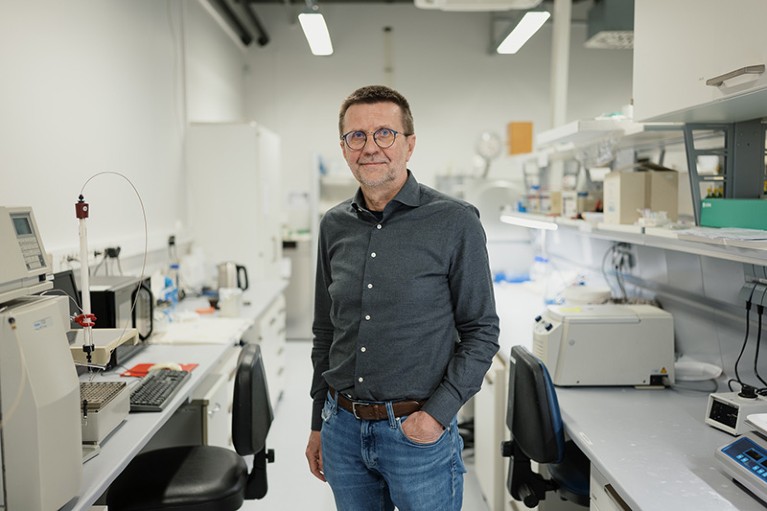

Biochemist Virginijus Šikšnys won a share of the Kalvi Prize in Nanoscience.Credit: Vilnius University Life Sciences Center Archive

On occasions, however, Lithuania’s strong history in biotechnology and the life sciences has been overlooked. The most notable example was when the work of Lithuanian biochemist Virginijus Šikšnys on CRISPR–Cas9 was rejected by the journal Cell.

Six years after the rejection, Šikšnys gained recognition for his work when he won a share of the prestigious $1-million Kalvi Prize in Nanoscience, alongside biochemists Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna, who are widely credited with co-inventing the gene-editing technology.

A steady return

Lithuania, however, has also faced an exodus of talent. The population decreased from 3.7 million in 1990 to 2.8 million in 2023. But this trend might be changing, owing to Lithuanians returning home from abroad and other nationals moving to the country. Since 2019, migration has exceeded emigration every year, with 87,367 people coming into the country in 2022, but only 15,270 leaving, according to the Lithuanian State Data Agency. Since 2017, the number of Lithuanians returning to their home country has risen steadily from 10,155 that year to 23,712 in 2021. There was a dip in 2022, possibly owing to the proximity of the country to the war in Ukraine.

According to the non-profit organization Invest Lithuania, which aims to attract foreign investment into the country, 57.5% of 25–34-year-olds have received tertiary education. This is among the highest of in EU countries and well above the EU average (41.2%). And of all students who began doctoral studies in 2021, 28% were in natural sciences, mathematics or statistics.

Jacqui Thornton’s travel and accommodation were provided by Go Vilnius, a tourism and development agency.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

This article is part of Nature Spotlight: Lithuania, an editorially independent supplement. Advertisers have no influence over the content.

[ad_2]

Source Article Link