[ad_1]

In 2010, astronaut Cady Coleman left her husband and young son to go into space.Credit: NASA/Bill Ingalls

Space: The Longest Goodbye Greenwich Entertainment Directed by Ido Mizrahy

Neither NASA nor the Chinese space agency are probably consulting screenwriters as they develop their plans to send humans to the Moon and Mars. But they need to take the problem of astronaut isolation seriously, as director Ido Mizrahy sets out in his heartfelt documentary Space: The Longest Goodbye. Released in cinemas and online this week, this thoughtful film shares first-hand accounts of how leaving family behind can wreak havoc on an astronaut’s well-being.

Any crewed trip to Mars, for example, will involve up to three years of spaceflight — a sea change in what humans have experienced so far. Russian cosmonaut Valery Polyakov holds the record for the longest-duration spaceflight: 437 consecutive days aboard the Mir space station from January 1994 to March 1995. He and other cosmonauts pioneered the study of how the human body responds to microgravity over time, from bone deterioration to muscle loss and vision changes.

Yet the psychological impacts of spaceflight are equally important, argues Al Holland, an operational psychologist at the NASA Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas, who drives much of the narrative for The Longest Goodbye. He and his colleagues studied NASA astronauts who flew on Mir, and used the lessons to try to improve astronauts’ mental health and well-being on board the International Space Station (ISS) during the 1990s. For example, carrying mechanical spare parts on board, which weren’t always stowed on Mir, reduced stress levels because astronauts knew that they had backups in case of an emergency.

Easing mental strain

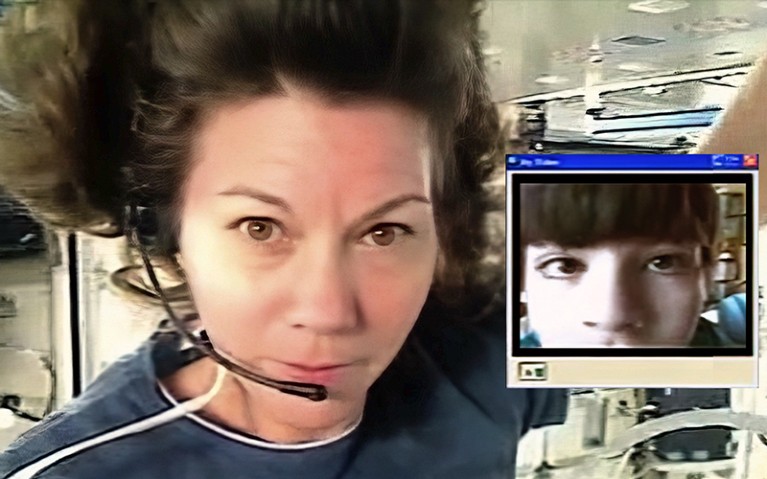

Holland’s team developed ways to lessen the psychological strain of separation, such as by providing twice-weekly audio- or videoconferences between astronauts aboard the ISS and their families, and phone calls home whenever needed. The Longest Goodbye explores these long-distance conversations poignantly, through video recordings shared by Cady Coleman, a NASA astronaut who spent 159 days aboard the ISS in 2010–11.

As Coleman speaks with her husband and ten-year-old son from orbit, they mimic her, drifting across the screen as they pretend to float in microgravity. In another call, Coleman and her son play a flute duet. But after being separated from his mum for so long, he begins to act up. As she reads a story to him, he gets off the couch and makes faces at the camera. He is often like this just before joining calls with Coleman, her husband tells her. From her screen, Coleman can’t do much more than raise her eyebrows sternly.

Coleman had frequent videoconferences with her son, but her absence was still hard on both of them.Credit: Cady Coleman

The video connection breaks up -repeatedly. Coleman cries on camera — a lot. In recent interviews for the film, her son talks about how he didn’t understand why she had to be gone for so long. It is a heartbreaking glimpse into the personal challenges of one of NASA’s most accomplished astronauts, and a warning for anyone thinking about taking a three-year trip to Mars. Being separated from your family for a long journey on Earth is challenging enough; being apart while enduring the unique stresses and dangers of spaceflight is much harder.

The film illuminates this while following the story of Kayla Barron, a NASA astronaut who flew aboard the ISS from November 2021 to May 2022. Barron is a former submariner who has experienced stressful military deployments, but says that going to space is very different. Just getting to orbit in the first place involves putting yourself atop a flaming rocket, she notes. “It’s the most dangerous thing you’ve ever done, and then you invite all of your family and friends to come watch it.” “My spouse is on top of this ball of fire,” her husband thinks.

The couple confronts the existential -question of whether, if she dies, she is doing what she wanted to be doing. In one scene, she rushes to shelter in a protected part of the ISS as an errant piece of space debris threatens to hit the station. Her husband sits helplessly at home, frantically trying to get updates.

Might spacefarers find other ways to -recreate human bonds? European Space Agency astronaut Matthias Maurer, who was on the ISS at the same time as Barron, is shown interacting with an artificial-intelligence assistant. It looks like a floating football and has a screen with a creepily simplified human face. Viewers are likely to be relieved when Maurer packs it away in its storage case.

Lessons on Earth

The film also recaps the rescue of 33 -Chilean miners in 2010, who had been trapped during a mine collapse and spent 69 days underground. Holland and other NASA employees advised the Chilean government on how to sustain the miners’ physical and psychological well-being during their extended isolation. They were told to eat and sleep on a strict schedule, and set up an illuminated area so they could transition between ‘day’ and ‘night’ while they awaited rescue. Lessons from space thus helped the miners to survive underground.

The Longest Goodbye doesn’t describe what might work best for astronauts on their way to Mars. But it does offer a poignant look at the isolation and loss of connection that so many astronauts feel in space, and that many of the rest of us might recognize a little from our own experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

[ad_2]

Source Article Link